This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!" by Richard Feynman. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What was Richard Feynman’s reputation when he was young? Why did he buy broken radios?

Though Richard Feynman’s recollections in his memoir may seem to bounce from topic to topic at random, they all exemplify certain key values that underlie Feynman’s idiosyncratic personality. They emerge in his childhood, developing his reputation early on.

Continue reading for an exploration of the young Richard Feynman.

The Young Richard Feynman

We’ll explore how the young Richard Feynman’s values shaped his lifelong approach to problem-solving, teaching, intellectual honesty, and living life to its fullest. At his core is a deep love of learning, which expresses itself in a variety of ways.

When Feynman talks about his life, one trait that stands out is his determination to understand how and why things work. He applied his curiosity to everything in life, not merely his scientific endeavors, and coupled it with a dogged persistence that made him stand out from his peers, often in unusual ways. Feynman’s childhood curiosity led him to pursue an education in math and science. But, as an adult, his curious nature expanded his horizons into fields such as safecracking and artistic expression.

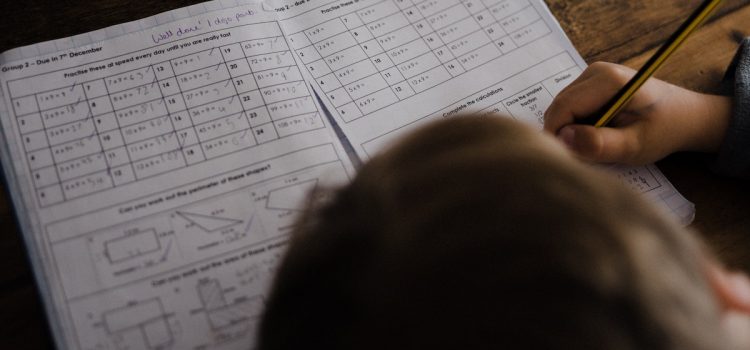

Feynman recalls that, as far back as his early teens, he was already tinkering with electronics. For him, it was more like play than formalized science or engineering. He didn’t follow any standard procedures—instead, he fiddled with wires, gears, and bulbs and observed what worked and what didn’t. He bought broken radios and tried to fix them, ran electrical wires all over his home, devised his own burglar alarm system, and almost inadvertently set his house on fire. Every project, both his failures and successes, was accomplished by nonstop trial and error. What Feynman took away from his early years was that persistence is the key to solving problems.

(Shortform note: Beyond simple perseverance, Feynman also demonstrated a willingness to take risks while viewing each failure as a learning opportunity. In Make Your Bed, Admiral William H. McRaven lists both these qualities—persistence and learning from failure—as essential ingredients for personal success. Since failure is an inevitable part of life, McRaven says that turning it to your advantage will better prepare you for future problems you’ll encounter. Meanwhile, persisting through your difficulties lets you remain in control of your life, whereas quitting before achieving a goal can only lead to frustration and regret.)

Feynman was so driven to solve problems that in school, he’d invent math puzzles for himself. This pushed him ahead of other students, who’d come to him with problems of their own. Feynman claims to have worked out many of the principles of trigonometry just for kicks and even invented his own form of mathematical notation because he didn’t like the ones used in his textbooks. All of this garnered him a reputation as a budding genius, a label that he frequently downplays, instead attributing his success to perseverance. He also says that, by approaching math and science as play, he worked out shortcuts to mathematical problems that made him seem smarter than he actually was.

(Shortform note: The way that Feynman downplayed his intelligence in favor of the process of working problems out indicates an attitude that likely enhanced his intellectual development. In Limitless Mind, educator Jo Boaler argues that labels such as “smart” or “gifted” are detrimental to children because they create the false belief that intelligence levels are fixed from birth instead of something you grow into. Students who struggle and work hard at solving problems end up creating more and stronger neural pathways in their brains than children for whom the answers come easily. As a result, learners like Feynman who relish the process of learning more than the end result end up being higher achievers over the long run.)

One thing Feynman discovered through his childhood exploration was that the world was a more complicated place than the simplified version in his textbooks, and this drove his curiosity further. When in college, he’d carry a toy microscope around campus so he could observe things such as ant behavior. When he took a summer job at a metal-plating company, he worked out chemical processes by trial and error, even though he wasn’t an expert in the field. Even in the case of puzzles where he could have looked up the answer, Feynman says that he didn’t because that would have spoiled the fun. To scratch his curiosity’s itch, he felt compelled to figure things out for himself.

(Shortform note: What Feynman describes is a process of experiential, self-directed learning, which can be practiced by anyone wishing to develop new skills and areas of expertise. In Ultralearning, Scott Young suggests that self-directed exploration can serve as both an enhancement and an alternative to traditional education. In particular, he touts the benefit of direct learning—the process of developing skills and ideas in the hands-on environment in which they’ll be applied, much like Feynman’s trial-and-error chemistry experiments while already on the job. Young says that key elements of direct learning are self-directed projects, immersion in the process, and holding yourself to high performance standards.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Richard Feynman's "Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman! summary:

- The memoir of award-winning scientist Richard Feynman

- A walk through Feynman's life, from college to winning the Nobel Prize

- Why enjoying life is just as valuable as your education