This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Hyperfocus" by Chris Bailey. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What is working memory? How does it affect your ability to be productive?

Your brain has a certain amount of working memory capacity. You can pay attention to only so much at a time. Naturally, this limitation affects your ability to get things done.

Continue reading to learn about working memory capacity and how it impacts productivity.

Working Memory Capacity and Productivity

Your brain isn’t optimized for the modern world in part because you can pay attention to only a limited amount of information. This has to do with how attention works in your brain.

When you pay attention to a task, it occupies some portion of your working memory. (Bailey refers to your working memory as your “attentional space.”) Working memory holds information that your mind is actively processing. Imagine it as your brain’s temporary storage solution: When your friend tells you their new phone number, you hold those digits in your working memory long enough to type them into your phone.

Working memory is essential to focus because focusing on a task requires you to remember information long enough to act on it. If you didn’t have a working memory, you wouldn’t be able to have a conversation: By the time someone reached the end of their sentence, you’d have forgotten what they said at its beginning, so you wouldn’t be able to understand their meaning.

The amount of working memory a task occupies depends on its complexity: The more complex a task, the more working memory it requires.

But your working memory can only hold so much information at a time. As Bailey notes, our conscious brains are incapable of processing too much information: Of the 11 million bits of information our brains process every second, our conscious brains can only process 40 of them. Therefore, you can only pay attention to the things that fit in your working memory.

Working memory capacity refers to the amount of information your working memory can hold simultaneously.

| The Difference Between Working Memory and Short-Term Memory Bailey’s explanation of attentional space is a little confusing, primarily due to his usage of the terms “mental scratchpad,” short-term memory, and working memory. He uses “mental scratchpad” to refer to both short-term and working memory, which implies that he’s using the terms interchangeably. But he then discusses how you hold something in your short-term memory after you focus on it, which implies that they are different. Compounding this confusion, the distinctions between the terms “short-term memory” and “working memory” are unclear in the academic field in general. Some researchers use the terms synonymously, but others don’t: Working memory usually “refers to structures and processes used for temporarily storing and manipulating information,” while short-term memory is “the capacity for holding, but not manipulating, a small amount of information in mind in an active, readily available state for a short period of time.” In our guide, we’ve exclusively used the term working memory for several reasons. First, Bailey refers most often to working memory. More importantly, the exact distinctions between working memory and short-term memory are tangential to his main point, which is that you can only pay attention to a limited amount of information at one time. |

So exactly how much information can you pay attention to simultaneously?

Studies suggest that the average person can hold only four bits of information in their working memory—and the maximum is seven. (Shortform note: The exact amount of information that fits in your working memory may depend on the type—studies suggest that people can hold seven digits but only five words.) Memorization techniques like chunking use this knowledge to their advantage: Remembering a list of 15 items is easier if you group it into three groups of five. (Shortform note: If you use this idea to memorize a random string of numbers, like Moonwalking with Einstein recommends, you might call it “arbitrary chunking,” since you arbitrarily impose the grouping and artificially create a unifying meaning for each chunk of numbers.)

Bailey argues that this cognitive limitation also explains why you often see groups of up to seven—like the days of the week—but rarely see groups beyond that. (Shortform note: A clear exception is groups of 12, like the months of the year, the 12 Apostles, or the 12 grades in school.)

How Many Tasks You Can Focus on at Once

As for tasks, Bailey identifies three general patterns of tasks you can focus on comfortably. (Shortform note: These patterns might not work for everybody: Research suggests that your working memory capacity peaks at young adulthood and declines as you age. Similarly, mental illnesses like schizophrenia and depression are associated with your working memory capacity.)

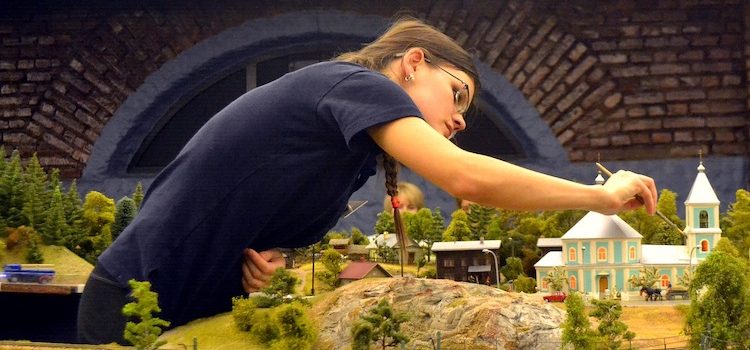

#1: You Can Focus on Multiple Simple Tasks

Bailey explains that many tasks are automatic and require little to no active intervention. Such tasks use very little working memory, partly because you do them mostly automatically. You likely expend some cognitive energy to begin these tasks, and there may be moments mid-task when the task demands more of your attention. But generally speaking, your brain reverts to autopilot mode once you get going. For example, beginning your skin care regimen might require conscious effort. If you put your lotion on the wrong shelf, you’ll focus on finding it. But otherwise, your skincare regimen likely doesn’t demand much conscious thought.

Since these tasks require so little attention, they’re the only kind you can successfully multitask: You can easily focus on them simultaneously.

#2: You Can Focus on One Complex Task and One Simple Task

Some tasks don’t require as much attention as writing a term paper, but they require more attention than drinking coffee. You can combine these tasks with a simpler task.

This is why you can listen to the radio as you get ready for work in the morning. You mostly pay attention to getting dressed and eating breakfast (the more complex tasks), but you direct a small portion of your attention to the radio (the simpler task).

| What Counts as a Simple Task Bailey refers to simple tasks as “habitual tasks,” which he defines as tasks that require “little mental intervention.” This seems self-explanatory, but his examples are somewhat confusing. For example, he defines grocery shopping as a habitual task. If you’re following a list, shopping for groceries requires little mental intervention. But if you decide what you want to buy while you’re at the store, shopping for groceries likely requires considerable mental intervention. Additionally, the better you get at a task, the less working memory it takes up. So buying groceries likely requires little mental intervention if you’ve been to the same store 100 times. But if you’re new to grocery shopping—or shopping in a new store where you don’t know the layout—the added layer of difficulty means the task takes up more of your working memory. The conclusion is likely that there is no universal definition of a simple task—how much working memory a task uses up differs based both on who does the task and how they do the task. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Chris Bailey's "Hyperfocus" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Hyperfocus summary :

- Why it's just as important to learn how to manage your attention, along with your time

- Why you still feel tired no matter how many breaks you take

- Strategies for managing your attention for better productivity and creativity