This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Stamped from the Beginning" by Ibram X. Kendi. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What role did William Lloyd Garrison play in the abolition of slavery? How did Garrison—though unknowingly and unintentionally—perpetuate racist ideas?

Though an advocate of total and immediate abolition of slavery, William Lloyd Garrison harbored a problematic stance towards Black people. Like many of his time, Garrison believed that Black people need white people to save them from slavery, lacking the capacity to break free themselves.

Here’s why Garrison’s views were racist, according to Ibram X. Kendi.

White Saviors

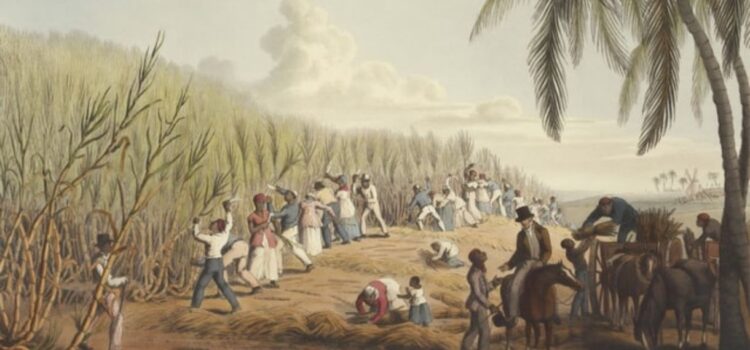

One of the counterintuitive insights of Kendi’s book is that it’s possible to oppose one form of racism while perpetuating another—as was the case with Garrison’s abolitionist movement, which was popular from the 1830s until the 1865 end of slavery. William Lloyd Garrison believed that Black people needed white people to rescue them from slavery and uplift their minds and spirits. Garrison argued that enslaved Black people should wait for white and free Black abolitionists to effect a political solution to slavery. (Yet, as Kendi notes, during the Civil War, thousands of Black people required no help to free themselves by running from their plantations, volunteering for the Union army, and so on.)

(Shortform note: Garrison’s view demonstrates what might today be called a white savior complex—a phenomenon that arises when white people attempt to help people from other racial groups in ways that reflect an attitude of superiority. While there’s nothing wrong with helping others, experts explain that the problem arises when white people assume that they have knowledge, skills, or resources that the affected group lacks and when they don’t take into account the wants and needs of the people they’re helping. Not only is white saviorism racist and insulting, it can make problems worse by convincing saviors they’ve solved a problem when they haven’t fixed the underlying inequities that caused the problem in the first place.)

Garrison wasn’t the only abolitionist to take a paternalistic stance toward the Black people he meant to help. Kendi points to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which had immense influence on the abolitionist movement. Kendi argues that the novel introduced the new racist stereotype of the extraordinarily spiritual Black person in Uncle Tom, a man weak of body but strong of soul. He explains that Uncle Tom played into preexisting stereotypes of weak Black men unfit to lead themselves—let alone a family, political movement, or nation. Portrayals like this reinforced the idea that Black people needed white people to come to their rescue.

(Shortform note: This spiritual-Black-people stereotype persists in the contemporary fiction trope of the “magical negro”—a stock character defined by his or her good sense, folk wisdom, and mystical powers (which may include healing, clairvoyance, or a special connection to God). Not only does the magical negro reinforce racist stereotypes, but it also marginalizes Black characters by reducing them to sidekicks, guides, or advisers to a white protagonist. Moreover, some scholars warn that when we depict Black people as possessing superhuman traits, we may raise the chances that police resort to violence when interacting with Black citizens.)

Imbruted By Slavery

Part of the justification for this paternalistic approach was the idea that slavery had turned Black people into the savages it claimed them to be. Kendi argues that this is classic assimilationist logic: Whereas enslavers argued that Black people were inherently inferior, many emancipationists argued that Black people had been made inferior by slavery’s abuses. Kendi points out that both of these stances are racist because both proclaim that Black people are inferior (they differ only in their assessment of who’s at fault for that inferiority). Yet, against Black protests to the contrary, many emancipationists clung to the idea that slavery had left Black people incapable of caring for themselves or joining in society.

| How to Defend Racist Policies by Decrying Racism One of the points Kendi makes throughout the book is that racist ideas are incredibly flexible—they can be stretched, twisted, and otherwise repurposed as needed to support essentially any racist policy. The idea that slavery made Black people inferior provides a particularly vivid example of this principle. As noted, this idea was initially conceived as racist argument against a racist policy (slavery). But in recent years, the inherent racism of this abolitionist stance has been used to defend ongoing racial disparities by attacking those who call attention to them. For instance, some conservative politicians and commentators have attacked Critical Race Theory (CRT)—an academic movement that studies the relationships between race, racism, power, economics, politics, history, and more—for its supposed anti-Americanism and anti-white racism. One common argument from this camp is that CRT teaches Black people to see themselves as helpless victims. The implication is that CRT itself is racist because it proposes that Black people are unequal—just as emancipationists suggested hundreds of years earlier. In a 2021 editorial, Kendi argues that this odd rhetorical inversion—which suggests that those fighting against racism are actually perpetuating it—is a political smokescreen designed to draw attention away from current policies that are actually causing racial inequity. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Ibram X. Kendi's "Stamped from the Beginning" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Stamped from the Beginning summary:

- How enslavers convinced themselves that slavery benefited slaves

- Why most antiracist reformers harbored racist thoughts

- How to achieve an antiracist society