This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Immediate Action" by Thibaut Meurisse. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What are the reasons behind why we procrastinate? Is evolution to blame for us putting things off?

Immediate Action by Thibaut Meurisse contends that procrastination may have an evolutionary cause. In the early stages of human evolution, people used to procrastinate as a survival mechanism.

Keep reading to learn why we procrastinate and the history behind the habit.

What Is Procrastination?

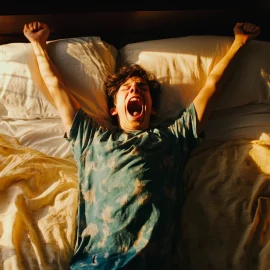

Meurisse defines procrastination as feeling resistant to working on the things that we know we need to do. The simple reason why we procrastinate is that we don’t want to work on a specific task. Meurisse writes that when you notice yourself procrastinating, you need to figure out why you’re resisting working on that particular task.

Even though procrastination makes it difficult for us to achieve our goals, we shouldn’t feel ashamed of it, according to Meurisse. In fact, everybody has the tendency to procrastinate, and we can’t stop procrastination altogether. But by learning why you tend to procrastinate and changing the way you approach the tasks on your to-do list, you can build more positive habits. Over time, those habits will make it easier for you to do the things you need to do, even when you don’t feel motivated to do them.

| What Have Psychologists Discovered About Procrastination? Meurisse’s idea that procrastination involves an emotional or impulsive decision is borne out by psychology research. Psychologist Piers Steel, author of The Procrastination Equation, explains that you typically choose to put off a task against your better judgment and even though you know the decision runs counter to your best interests. Steel even refers to procrastination as “self-harm”: He points out that when you act on the impulse to procrastinate, not only are you aware that you’re delaying something you need to do, but you also know that the delay might cost you later. Many researchers also believe that procrastination involves trouble managing emotions, not time. Psychologist Fuschia Sirois, author of Procrastination, explains that you postpone a task because you don’t want to confront the negative emotions like boredom, anxiety, and frustration you associate with the task. But Sirois explains that to stop procrastinating, you have to find an alternative way to deal with those emotions. Practicing a skill called self-compassion—which involves being kind (instead of judgmental) to yourself, realizing that everyone procrastinates, and avoiding identifying strongly with a negative self-image—can help you decrease your distress and increase your motivation to get the task done. Even though it’s irrational, everyone procrastinates occasionally, and researchers estimate that about 20% of adults in the US procrastinate chronically. We justify our procrastination with all kinds of excuses. But clinical psychologist David Ballard explains that the first step to solving procrastination is taking a hard look at why you’re really putting off a task, as Meurrise suggests. Once you have a clearer picture of which tasks you tend to postpone—and whether you tend to have issues with scheduling, feel overwhelmed by big tasks that could be broken into smaller pieces, or struggle with delayed gratification or distraction—you can start addressing that underlying cause. |

Why Do We Procrastinate?

Though we all know what procrastination feels like, few of us have thought about why we’re so easily tempted to put things off. Meurisse contends that procrastination is a holdover from earlier stages of human evolution where it served a purpose: When we lived in dangerous environments, our brains needed to protect us from expending energy and taking risks on tasks that weren’t vital to our survival (or our ability to reproduce).

He writes that when you feel compelled to put off a task, it may be because your brain perceives the task as either an unnecessary use of your limited energy or as a potential risk to your physical well-being. After all, your brain has evolved to maximize your chances of survival: Its goal isn’t necessarily to motivate you to take actions that will help you thrive. Meurisse notes that while procrastination served a purpose earlier in human evolution, it can hold you back from accomplishing your goals if you let it get the better of you.

| Is Procrastination an Effective Survival Mechanism? If procrastination evolved to help us survive, as Meurisse contends, then how well did it serve that purpose? Quite well, evidence suggests. Physician Sharad P. Paul, author of The Genetics of Health, notes that procrastination has been passed down through generations of humans (and still plagues modern humans today), which indicates that procrastination was effective in helping our ancestors to survive longer. Early humans who spent time in the safety of their caves, sharpening their tools or perfecting their battle strategy, probably stayed out of conflict and out of harm’s way. That made them more likely to live long enough to reproduce and to pass the trait of procrastination along to their children. Some scientists understand procrastination as the result of a conflict between two parts of your brain, including one that evolved to protect early humans from danger. When you face a difficult or unpleasant task, the limbic system (an evolutionarily older part of your brain involved in your emotional responses) and the prefrontal cortex (an evolutionarily newer part of your brain involved in decision-making) compete to determine how you’ll behave. When the limbic system wins, you tend to put the task off until later. And it turns out that the limbic system wins a lot: That’s because its responses are almost automatic, and that speed helps it make sure you survive to see (and procrastinate) another day. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Thibaut Meurisse's "Immediate Action" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Immediate Action summary:

- How procrastination was useful in early human evolution—but not anymore

- How to face your procrastination habit head-on and build healthier habits

- Why we tend to do nothing when we have too much to do