This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "You're Not Listening" by Kate Murphy. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Why don’t people listen? If listening is so important and beneficial, then why aren’t people doing it?

Everyone would agree that listening is a critical skill. But, many people aren’t stellar listeners. When you understand why people don’t listen, you’ll be in a better position to work around and perhaps even overcome the roadblocks.

Continue reading to learn about common barriers to listening.

Why People Don’t Listen

Why don’t people listen? Murphy identifies four common barriers to listening: distracting technology, discomfort, a culture of self-centeredness, and assumptions about other people.

Barrier #1: Distracting Technology

Murphy argues that people don’t listen well because they’re distracted. She explains that people are prone to distractions because the human brain thinks much faster than people speak. Therefore, you can easily get bored with someone speaking and focus on something else.

While listening without distraction may be difficult under normal circumstances, Murphy suggests that two recent developments in technology have made this problem even worse: increased background noise and technology designed to distract.

1) Increased background noise breaks the listener’s concentration. Murphy contends that we live amid higher levels of background noise than ever before. In public and private spaces, people are used to constant music or television playing in the background. This pulls people’s attention away from their conversations.

2) Technology is designed to distract. Murphy states that many software companies use information about psychology and neuroscience to design apps that are hyperstimulating and addictive. This distracts people because they’re always tempted to check their apps. Furthermore, these apps condition people’s brains to crave a higher level of stimulation. This makes it even harder to pay attention as normal conversations won’t be as stimulating.

| The Science Behind Distraction Murphy identifies three core reasons we have such a hard time with distraction: boredom, background noise, and overstimulation. Here we’ll review scientific key findings on each of these problems and discuss how they relate to disrupted attention. 1. Boredom: Psychologists have defined boredom as an experience when 1) people have difficulty paying attention or engaging in an activity, 2) they’re aware of it, and 3) they consider the environment responsible for their situation. People find boredom so distressing that it’s linked to adverse outcomes in life like anxiety, depression, binge eating, drug and alcohol abuse, and gambling addiction. However, researchers argue that how people react to boredom determines how much it will distract their attention. Those who find ways to keep their mind stimulated while staying on task can overcome this powerful feeling. 2. Background noise: Unfortunately, you may not have much control over how distracting you find background noise. Research has shown that some people are much more sensitive to background noise than others, which may be genetic. Noise-sensitive people who are often exposed to excessive loud background noise are also at greater risk for health problems like sleep disturbances and heart disease. 3. Overstimulation from technology: There are conflicting views on whether technology diminishes people’s attention span. Some mental health practitioners report that patients struggle to control their focus if they become too used to the immediate gratification of electronic media. However, some studies have shown no difference in attention spans between frequent and infrequent users of social media, suggesting that this correlation may be overhyped. |

Barrier #2: Discomfort

Murphy points out many people have trouble listening because they find it uncomfortable. She highlights two distinct ways listening makes people uncomfortable: It forces them to deal with uncomfortable silences and it exposes them to views that challenge their beliefs.

1) Uncomfortable Silences

Murphy explains that listening causes discomfort because it requires you to be silent—and many people find that silence distressing. Therefore, many people try to fill up the silence by talking. The pressure to avoid silence creates two problems for effective listening.

- To avoid silence, listeners will often think about how they’ll respond when the other person finishes talking instead of paying attention.

- Listeners will also jump in and speak as soon as they notice a pause coming up—whether or not the other person has finished speaking. This prevents the speaker from finishing their thoughts and sharing what’s on their mind.

(Shortform note: Researchers may have pinpointed why silences in conversations can be so uncomfortable. Studies show that when conversations flow naturally without awkward pauses, people feel a greater sense of belonging, validation, and self-esteem. Conversely, when awkward pauses break up conversations, people fear exclusion and incompatibility. Therefore, people may rehearse their responses and interject prematurely because they fear exclusion and incompatibility. However, by charging ahead with the conversation instead of listening, they may actually increase the likelihood of an awkward, incompatible conversation.)

2) Views That Challenge Your Beliefs

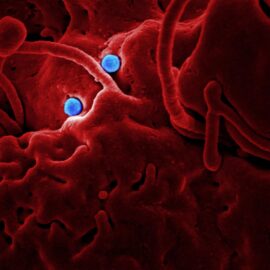

Murphy asserts that listening can also be uncomfortable because it exposes you to views that challenge your beliefs. Citing research, she says confronting views contrary to your own activates the same parts of the brain as physical danger. Therefore, listeners may steer the conversation away from uncomfortable topics or avoid listening to certain individuals altogether. This leads people to listen to each other less on topics they find uncomfortable.

(Shortform note: To ease the discomfort of political debate, experts on political dialogue recommend finding common ground with someone before talking about politics. They argue that forming close personal ties creates trust, and trust enables people to listen to each other when they disagree politically. Therefore, if a subsequent political conversation gets heated, you can fall back on that shared trust and mutual respect.)

Barrier #3: A Self-Focused Culture

Murphy explains that people also don’t listen to each other because their culture encourages them to be self-centered. Society teaches that in order to belong and to deserve others’ attention, people need to prove their worth by displaying it to others. This encourages people to talk more about themselves during conversations instead of listening to others.

Murphy notes that, paradoxically, talking about yourself all the time may diminish your feelings of worth. Recall that listening to others creates a sense of empathy and connection. Many people derive their sense of self-worth and belonging from these feelings—but if someone always talks instead of listening, that essential feeling of connection can’t happen. Therefore, in trying to display their worth all the time, someone may feel less self-worth and belonging than if they gave others a chance to speak.

(Shortform note: Similarly, psychologists have found that people overestimate how much fun they’ll have talking about unique experiences that set them apart and underestimate how much fun they’ll have talking about mundane experiences they have in common with others. In studies, participants felt more satisfied after talking about a mundane experience that everyone shared than after talking about an extraordinary experience that only they had. This happens because points of commonality lead to richer experiences of mutual engagement.)

Barrier #4: Making Assumptions

Murphy states that people also fail to listen effectively because they’ve formed assumptions about the person speaking. When you rely on your assumptions about others, you become less curious about who they are and what they have to say. This will lead you to listen less—there’s no need to listen if you already know what they’ll say. Therefore the assumptions listeners hold about the person speaking become an obstacle to effective listening. Murphy identifies two main reasons why people make assumptions: stereotyping and personal familiarity.

- Stereotyping occurs when someone makes assumptions about another person based on external characteristics or social categories. Murphy points to a common modern example of this: assuming that someone has bad morals or character because of the political camp they fall into.

- Paradoxically, knowing someone really well can make you listen to them less. This happens because when you feel you know someone very well already, you become less curious about them and believe that you have less to learn. This lack of curiosity leads listeners to “tune out” when someone is speaking and therefore listen less effectively.

| Why We Tune Others Out—and How to Stop It We can overcome the negative impact of our assumptions on listening if we have a clearer sense of why this happens and what experts recommend. Neuroscience has shed light on why we’re so likely to tune out things when we believe we understand them. Because the brain’s attention is a limited resource, we’re hardwired to spend it on the information we need most to survive. Therefore, our brains naturally look for changes in our environment and new developments that we need to process and understand. This is why people can naturally ignore the sound of fans or clocks. Their brains don’t notice the sounds because they’re so consistent. There are a couple of strategies to help break through this automatic tuning out: To overcome stereotypes, experts advise first educating yourself on possible stereotypes you may hold about others. They also recommend individuating others, that is, elevating their individual traits over group ones. Finally, they recommend staying in contact with people from the stereotyped group. A lack of experience with a group makes it easier to maintain stereotypical views. To overcome familiarity in your relationship, experts advise trying a new activity together, going to a new place together, or even talking about something you don’t usually discuss. Any new stimulation has the power to wake your brain up again to attentiveness. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Kate Murphy's "You're Not Listening" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full You're Not Listening summary:

- A look at how listening skills are disappearing throughout society

- How to become a better, more effective listener

- Why it's easier to listen to strangers than to those close to you