This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Wired for Story" by Lisa Cron. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Why do people like stories? What answer can we find in the reason why storytelling developed in the first place?

Stories aren’t just entertaining; they also satisfy a neurological need that humans evolved over millennia. That’s the view of Lisa Cron, who argues that our brains evolved to absorb important survival information through stories.

Read more to understand why Cron urges writers to write in a way that satisfies our brains’ expectations of story.

Why People Like Stories

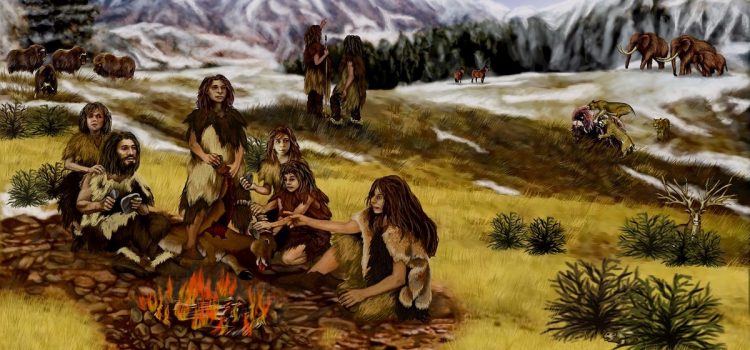

Why do people like stories? To answer that question, Cron goes back way in time and takes a neurological perspective. She explains that storytelling was developed to help us remember important information and use that information to make predictions. This allowed us to survive difficult challenges by preparing for them without having to experience the dangerous situations firsthand. For example, an ancient hunter-gatherer who had a close call with a bear might regale their community with that harrowing tale, giving them important survival knowledge, like where they might expect to encounter bears and tips for how to get away unscathed (don’t run from it, and don’t try hiding in a tree either!).

| Ancient Storytelling Some experts argue that the majority of stories that ancient people told while gathered around the fire were not necessarily adventure stories but were instead family stories that helped to establish and pass down a familial and cultural identity. They suggest that these stories were particularly impactful for children, noting that children of families that tell more intricate stories tend to have better self-esteem and emotional well-being (which also helps prepare us to survive difficult challenges in life). Because of the oral nature of early storytelling, it’s not possible to know when fictional storytelling arose, but the earliest known fictional story was The Epic of Gilgamesh, believed to be around 4,000 years old—more than 300,000 years after humans evolved to our current level. |

In order for us to pay attention to these stories, they had to be presented in a way that appealed to how our brains process information. This caused us to develop expectations for what a story should be like, and, if a story doesn’t meet these expectations consistently, we won’t keep listening—or reading. Cron explains that because these expectations are so hardwired, they’re instinctive, and so we’re not able to easily explain what makes a good story, which is what makes writing one so difficult.

(Shortform note: Our expectations of stories are so powerful that storytellers who’ve mastered the art can sometimes use them to manipulate or mislead us. By presenting harmful ideas in a way that taps into our brains’ instinctive expectations, some people can convince us to view certain groups as enemies or make poor business decisions, among other things. Some experts suggest that this was the case with Theranos, a company that promised an unattainable medical technology but used a compelling story to sell investors on the idea and convinced them to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in the company.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Lisa Cron's "Wired for Story" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Wired for Story summary:

- How humans have a neurological need for stories

- The formula that the human brain expects to encounter in a story

- How to build a protagonist that engages your reader