This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Mediocre" by Ijeoma Oluo. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

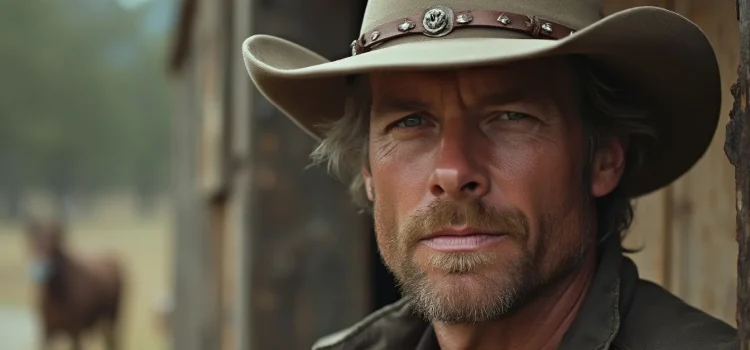

Do you know the origins of white masculinity in America? How does the cowboy myth influence modern-day extremism?

Ijeoma Oluo explores the concept of white masculinity through the lens of the American cowboy archetype. She argues that this idealized image of rugged individualism and conquest has far-reaching consequences, shaping attitudes and behaviors in contemporary society.

Continue reading for a thought-provoking journey through American history and culture.

Origins of White Masculinity

According to Oluo, white American male culture is exemplified by the image of the cowboy—the rugged, violent conqueror who defends his independence at all costs and stands alone as the civilizer of the West. She argues that many white men, wanting to see themselves as heroes, take on the cowboy persona, which in turn causes them to look for enemies to justify their adopted sense of vigilance and aggression. She suggests that this persona of white masculinity explains why some white men are quick to see their Black fellow citizens as criminals or their Muslim fellow citizens as terrorists—sometimes with deadly consequences.

(Shortform note: The mythological cowboy symbolizes the idea of rugged individualism that first emerged in the context of the US’s western frontier. Rugged individualism proposes that each person is fundamentally free, self-directed, and self-reliant. In White Fragility, Robin DiAngelo argues that this brand of individualism tends to affirm white supremacy by suggesting that elite white people are elite through their own efforts and that people of color who are struggling are struggling due to their own failings—thereby ignoring factors such as social inequity, family background, and luck.)

Oluo says that this cowboy persona is based on a myth contrived to gloss over the deliberate genocide of native peoples by casting the victims as brutal savages and the perpetrators as defenders of civilization. She gives the example of Buffalo Bill Cody, a 19th- and early 20th-century showman, hunter, and soldier. Cody initially came to prominence for his skill at massacring buffalo—a practice employed to starve the Indigenous American population who relied on them for food. He later gained widespread fame and success by creating an Old West stage show that celebrated his buffalo hunts and glorified incidents such as his killing and scalping of a young Cheyenne warrior.

(Shortform note: Although Cody was himself a symbol of American expansionism and the subjugation of native peoples, decades after his death, he ironically became a symbol of anticolonial sentiment in what’s now the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). In the 1950s, with the DRC under Belgian rule, a number of young native Congolese people formed street gangs inspired by American Western movies recently imported into the country. These young people dressed like cowboys and called themselves “Bills” after Cody’s stage name. According to one historian, these Bills played a pivotal role in kindling the uprising that led directly to the DRC’s independence in 1960.)

Despite the US’s legacy of expansionist violence, Oluo argues, the cowboy persona is still especially prevalent in the modern-day American West, where it’s evolved into a variety of religious extremist, militia, and anti-government movements that emphasize white male sovereignty. She illustrates this contemporary extremism by pointing to the Bundys, a ranching family who staged several armed standoffs with the US government over their alleged right to graze their cattle on public lands without paying fees or respecting rules.

(Shortform note: Though Oluo presents the Bundys and their followers as a relatively isolated fringe interest, the 2014 Bundy standoff was influential in spreading anti-government extremism beyond the American West. According to a former member of the Oath Keepers—a paramilitary group that was heavily involved in the January 6, 2021 attack on the US Capitol—the 2014 standoff inspired increasingly radical and violent behavior by the group and others like it.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Ijeoma Oluo's "Mediocre" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Mediocre summary:

- Why underqualified white men are in powerful positions

- How toxic white men have reacted to social progress

- The presence of white supremacy in American football