When did humans develop consciousness? How did the development of writing fundamentally change the way our ancestors thought and made decisions?

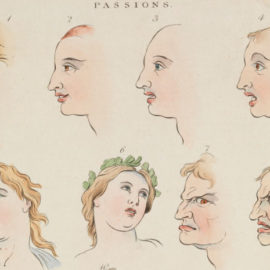

Julian Jaynes proposes that early humans relied on auditory hallucinations—voices they attributed to gods—rather than self-reflection for guidance. He believes that humans developed consciousness gradually as societies became more complex.

Keep reading to explore Jaynes’s theory about how humans developed consciousness as we experience it today.

When Humans Developed Consciousness

Jaynes posits that the bicameral mind served early human societies effectively but that this mental organization eventually proved inadequate for an increasingly complex world. So, when did humans develop consciousness? As societies evolved beyond rigid hierarchies, they faced new challenges: population growth, trade networks that exposed people to diverse beliefs and practices, invasions and natural disasters that disrupted established patterns, and—perhaps most significantly—the invention of writing. The third core idea of Jaynes’s theory is that these mounting pressures demanded more sophisticated ways of processing information and making decisions than the bicameral mind could provide.

Jaynes contends that writing, in particular, catalyzed the breakdown of the bicameral mind. When messages that had previously been experienced as auditory hallucinations could be written down, they became visible, permanent, and—crucially—controllable. People could now access and interpret information independently, rather than relying on hallucinated voices for guidance. As written communication became more prevalent, people gradually relied less on the auditory hallucinations generated by the right hemisphere of their brains. The voices of the “gods” lost their commanding influence, becoming less effective at directing behavior until they eventually faded away.

(Shortform note: Jaynes’s theory that consciousness emerged to help humans cope with increasing social complexity parallels the social brain hypothesis. This theory suggests that living in large social groups drove the evolution of bigger, more sophisticated brains. Evolutionary psychologists have found that the size of a species’ typical social group correlates strongly with the scale of brain regions involved in social intelligence. For humans, this relationship predicts a natural group size of around 150 people—a number consistently found across various cultures and time periods.)

The shift away from the bicameral mind created a fundamental change in how humans experienced their world. As the hallucinated voices became less reliable guides—particularly during times of social chaos when different “gods” might give conflicting instructions—people needed a new way to organize their mental processes. The solution that emerged was consciousness: an internal representation of the self that could create coherent narratives from experience and make independent decisions. This new mental faculty enabled people to reflect on their choices, imagine different possible futures, and take responsibility for their actions.

(Shortform note: Jaynes’s view that writing transformed human cognition aligns with the views of other experts who study how technologies change how we think. Early writing systems like cuneiform allowed people to store and process information outside their minds, fundamentally altering our relationship with knowledge. This pattern continues today: Modern technologies like smartphones and the internet further externalize our memory and cognitive processes, changing how we interact with information just as the advent of writing did.)

Jaynes explains that the shift toward consciousness wasn’t instantaneous but gradual, likely accelerating during periods of social upheaval when traditional ways of thinking proved insufficient. As people learned to rely on their own judgment rather than divine guidance, they developed new capabilities for self-reflection, abstract thinking, and decision-making—the hallmarks of consciousness as we know it today.

(Shortform note: As Jaynes acknowledges, major cognitive and social changes can be disorienting even when we can make sense of them through narrative. Rebecca Solnit (Men Explain Things to Me) suggests that embracing uncertainty and maintaining hope are crucial for navigating such transitions. She compares progress to underground growth that’s invisible until mushrooms suddenly appear—an apt metaphor for how our ancestors might have experienced their gradual evolution toward consciousness.)