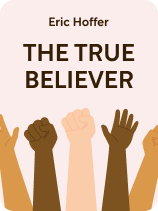

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The True Believer" by Eric Hoffer. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What is a true believer? What types of people are most susceptible to joining mass movements?

In his book The True Believer, Eric Hoffer explores the psychology behind mass movements and their followers. He identifies several groups of people who are particularly drawn to these causes, including the marginalized, the unfulfilled, the guilt-ridden, and the self-interested.

Read more to dive deeper into Hoffer’s insightful analysis of what makes a true believer.

What Is a True Believer?

While mass movements speak to universal human needs, according to Hoffer, there are some groups who are more susceptible to the call of mass movements than others. These are what he calls the “true believers.” So, what is a true believer? Hoffer describes them as people who are dissatisfied with their current state but not completely preoccupied with their own survival. He argues that, if someone is satisfied they have no reason to seek change—and, conversely, if someone is focused only on meeting their basic needs, they don’t have the capacity to put energy toward making change.

(Shortform note: While Hoffer suggests that those most susceptible are people dissatisfied with their current state but not solely focused on survival, real-world examples show a broader range of participants in mass movements. For example, in 1930, Mahatma Gandhi’s Salt March drew thousands of impoverished Indians to protest the salt tax—a critical issue for them. Meanwhile, climate change activists, like Greta Thunberg, show that even those who aren’t personally dissatisfied with their life circumstances can be motivated by broader concerns for ecological impact and future generations. These examples challenge Hoffer’s theory by revealing the diversity and complexity of motives fueling people’s engagement in significant social changes.)

Hoffer identifies several subsets of a population that meet the criteria of “true believer.”

#1: People Who Are Marginalized

People who are marginalized are more likely to be true believers. According to Hoffer, marginalized groups often experience a profound sense of exclusion from mainstream society, whether that’s because of economic hardship, racial or ethnic discrimination, or simply a failure to conform to societal norms. For marginalized people, mass movements offer a sense of belonging and identity that they feel is denied to them elsewhere. The promise of change that these movements offer is appealing because it gives hope for a more inclusive future where marginalized people are recognized and valued in mainstream society.

For example, the Indian Independence Movement was driven by Indians from many different walks of life who faced economic exploitation, racial discrimination, and political marginalization under British rule. These conditions fostered a deep sense of exclusion from the benefits of their own country’s wealth and governance. The movement’s promise of freedom and justice was incredibly appealing, offering hope for a future where Indians could govern their own country, free from foreign domination and exploitation.

(Shortform note: In Caste, Isabel Wilkerson’s discussion of modern caste systems provides a deeper understanding of why marginalized groups, as described by Hoffer, are so drawn to mass movements. According to Wilkerson, the rigid social hierarchies inherent in a caste system foster a sense of alienation and invisibility among those at the lower rungs of the societal ladder. Mass movements, therefore, become not just appealing but essential for these groups, as they offer both visibility and the promise of dismantling or disrupting the very caste barriers that marginalize them. In this context, such movements do more than offer hope—they provide a platform for asserting value and claiming rightful space within mainstream society that the rigid structures of caste would otherwise deny them.)

#2: People Who Are Unfulfilled

People who are unfulfilled or bored are more likely to be true believers. When everyday life lacks stimulation or meaning, the explosive energy and purpose that a mass movement provides can seem irresistibly stimulating—a remedy for ennui. This lack of fulfillment drives individuals toward activities that promise significance beyond mundane routines; mass movements offer not just distractions but the opportunity for grandiose and life-affirming causes.

For example, the Arab Spring, which began in late 2010, was a series of anti-government protests, uprisings, and armed rebellions that spread across much of the Arab world. For many young people in these regions, everyday life was marked by unemployment, political oppression, and a lack of opportunities, leading to a profound sense of stagnation and disconnection. The Arab Spring offered something dramatically different from their daily routines. It presented a potent combination of excitement, purpose, and the possibility of meaningful change. The promise of contributing to a cause that could overthrow dictators, demand democratic reforms, and reshape nations was invigorating.

(Shortform note: Psychological research suggests that boredom is not merely a trivial annoyance but a complex emotional state that can lead to significant behavioral changes. Research shows that when people are bored, they’re motivated to seek out any kind of stimulation, whether positive or negative. For example, in a study where participants were asked to sit quietly with their own thoughts for 15 minutes, many preferred to give themselves an electric shock rather than experience boredom: Nearly half of the participants chose to press a button to produce the shock, even though they’d previously reported disliking the sensation and saying they’d pay to avoid it.)

#3: People Who Feel Guilty

People who feel guilty are more likely to be true believers. Hoffer discusses people who live with guilt over their past actions, whether the transgressions are real or imagined. According to Hoffer, mass movements offer these individuals redemption through renewal: a path away from self-reproach toward absolution. By participating in something they see as pure or noble compared to their past deeds, they find relief from their guilt while contributing to what they perceive as a greater good.

For example, during the Crusades, many Europeans who joined the movement were motivated by the promise of indulgences—the Church’s offer of forgiveness for all past sins to those who took up the cause to reclaim the Holy Land from Muslim rule. The Church portrayed the Crusades as a noble and holy war, a fight not just for territory but for the soul of Christendom itself. Participation was seen as an act of ultimate devotion, a way to atone for sins and achieve salvation.

(Shortform note: Research suggests that the motivating effect of guilt can vary depending on cultural context. A broad international study spanning eight countries, including the United States, Japan, and Indonesia, found that personal and collective values shape the way people feel guilt, shame, and regret after wrongdoing. Researchers found that in places with strong collectivist orientations—where community well-being is prioritized over the individual—people tend to feel these emotions more intensely. Contrarily, individualistic societies might not feel the same level of collective remorse.)

#4: People Who Are Self-Interested

Finally, people who are self-interested are more likely to be true believers. Hoffer points to people who are self-interested as prime targets for the lure of mass movements. Mass movements often promise a significant upheaval in the social order or a redistribution of power and resources. For those primarily focused on their own advancement or personal gain, aligning with mass movements can seem like an efficient way to achieve their goals under the guise of a broader ideological commitment.

For example, the French Revolution (1789-1799) aimed to dismantle the ancient regime of monarchy, aristocracy, and clerical dominance, advocating instead for liberty, equality, and fraternity. While many participants were driven by the genuine desire for societal transformation and the establishment of a more equal society, others exploited the upheaval to seize property, gain political power, or elevate their social status. Figures like Maximilien Robespierre and Napoleon Bonaparte, for instance, began as revolutionaries advocating for change but eventually used the revolution’s momentum for significant personal and political gain, with Napoleon ultimately crowning himself Emperor.

(Shortform note: Hoffer suggests that people who look out for themselves might see an opportunity in mass movements, hoping to climb the social ladder during times of upheaval. But even if the self-interested are initially drawn to the group for personal benefit, they might eventually align themselves with the collective goals due to deeply ingrained human tendencies. As Robert Cialdini points out in his book Influence, we’re often swayed by things we don’t notice, like giving back when someone’s done us a favor (reciprocity) or doing what everyone else is doing (social proof). So these self-interested joiners might, without even realizing it, start to actually believe in and fight for the cause they signed up for just to get ahead.)

Exercise: Practice Critical Thinking

Hoffer suggests that blind faith in any cause or ideology often entails a surrender of independent thought. To guard against this, we can cultivate habits of critical thinking.

- Are there any beliefs or ideas you’ve accepted without question? What steps can you take to gather more information or diverse viewpoints on this issue?

- Describe how you will respond the next time you encounter a viewpoint that opposes your own. What can you do to ensure you give divergent viewpoints a fair and critical evaluation?

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Eric Hoffer's "The True Believer" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The True Believer summary:

- Why people are drawn toward mass political, social, and religious movements

- Four types of people who are particularly susceptible to mass movements

- How mass movements evolve and why they succeed