This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Gut" by Giulia Enders. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What happens in the small intestine? What is the role of the small intestine in the digestive process?

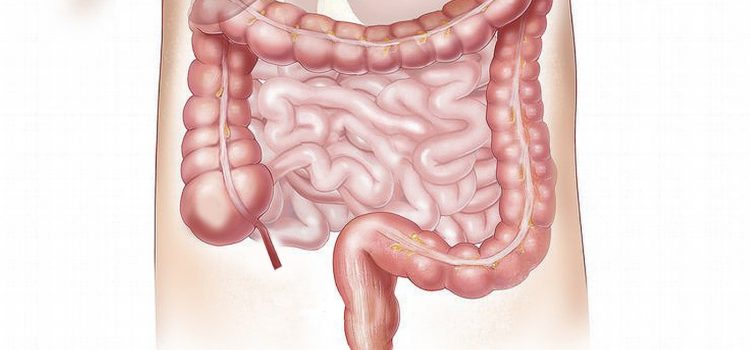

The small intestine’s job is to absorb the food particles found in chyme into the bloodstream. From there, the particles travel throughout the body, providing fuel for our cells and building important structures.

Keep reading to learn how the job of the small intestine.

The Small Intestine

What happens in the small intestine during digestion?

There are three important parts to the small intestine’s job: 1) breakdown, 2) absorption, and 3) cleanup. Let’s look at each in turn.

Step 1: Enzymes and Digestive Juices Break Down Chyme

Enders explains that as the chyme enters the small intestine, the liver and pancreas release enzymes and digestive juices through a small hole called the duodenal papilla. These juices break down any food that wasn’t fully broken down in the stomach.

Step 2: Villi and Microvilli Absorb Nutrients

Once digestive juices and enzymes have broken down the chyme even further, what happens next is that the small intestine begins to absorb macronutrient molecules.

To do so, Enders explains, the small intestine has a massive surface area, full of twists, turns, and folds. Tiny, fingerlike protrusions called villi pepper its surface, joined by their smaller relatives, microvilli. Enders claims that if all of these folds, villi, and microvilli were ironed out into a straight, smooth line, it would measure four and a half miles in length.

(Shortform note: Enders’s presentation of this statistic is slightly misleading. Her point is that the small intestine has a massive surface area. However, in doing so, she conflates surface area and length. Most estimates place the length of our small intestine at around 22 feet, or 0.004 miles.)

Synchronized by bioelectric pulses, the villi and microvilli move the chyme through the small intestine. They also absorb carbohydrate and amino acid molecules into the bloodstream. These molecules then travel to the liver, which filters out bad particles such as toxins.

Whereas carbohydrates and amino acids directly enter the bloodstream, fat must take a different route. Enders explains that our villi and microvilli can’t absorb fat because it’s not soluble in water. Instead, our lymphatic system brings fat from our gut directly to our heart, which then pumps it to the liver for screening.

(Shortform note: Fat going “directly to the heart” sounds scary given the connection between the overconsumption of unhealthy fats and heart disease. However, the structure of our lymphatic system is not the reason that fat can cause heart disease. Instead, a recent study suggests that food high in saturated fat makes us more susceptible to harmful bacteria. These bacteria can damage our small intestine and make it harder to absorb saturated fat, increasing the risk of heart disease.)

Step 3: A Wave of Leftovers Cleans the Small Intestine

About an hour after digestion, the stomach happens to send whatever leftovers remain into the small intestine. Enders describes this as a wave that cleans the gut, creating the gurgling sound that we often associate with hunger. (Shortform note: The technical term for this gurgling sound is “borborygmi,” and it can be louder or more frequent depending on the amount of gas in the gut.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Giulia Enders's "Gut" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Gut summary :

- How your digestive system works and why it’s important to keep it healthy

- How tiny organisms in your intestines influence your immune system (and possibly your mood)

- What your appendix actually does