This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Cynical Theories" by Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What are critical theories? How are they a new take on postmodernism? Why are they popular?

Authors, academics, and cultural critics Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay dive into the history of social justice in their book Cynical Theories. They believe the movements started out on a positive note but eventually became corrupted through critical theories.

Read on to understand what critical theories are, including their methods and doctrines.

Critical Theories

The authors explain that deconstructive postmodernism was the second phase in the history of social justice. Pure deconstructive postmodernism, which began in the 1950s, wore itself out after only a few decades. Because early postmodernists didn’t believe in objective truth, they couldn’t make any arguments about how things are or should be, causing the mostly academic movement to stagnate. However, a newer generation of academics, artists, and activists in the 1990s through the 2010s modified postmodernism into critical theories.

So, what are critical theories? The authors explain that academic fields aim to “critique” culture by noticing and challenging specific hierarchies. For example, the academic field of critical race theory “critiques” the idea of race as a whole, challenging those who believe in it.

Pluckrose and Lindsay suggest critical theories became popular because many of the main political goals of past activists were achieved—homosexuality was decriminalized, workplace sexual harassment was made illegal, and so on. Modern social justice activists, therefore, turned away from material approaches and flocked to the culture-and-language-based approach of postmodernism.

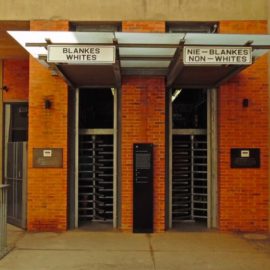

(Shortform note: To show how critical theorists abandoned and critiqued past approaches to social justice, we can look to legal scholar and critical race theory founder Derrick Bell’s view of Brown v. Board of Education. The case is a good example of a liberal approach to social justice since it used an existing institution—the US Supreme Court—to achieve a specific legal goal—outlawing racially segregated schools. But according to Bell, Brown v. Board of Education failed to truly provide equal education to all races. He argues that using the law to further integrate schools is the wrong approach to equality. Instead, he says society should invest more in both desegregated and majority-black schools to improve both.)

The authors outline two main components of critical theories:

#1: Postmodern Methods

While critical theories don’t subscribe to the total deconstruction of pure postmodernism, they still use methods influenced by postmodern thought. Critical theories still deconstruct dominant narratives and look for hierarchies within language, culture, and everyday interactions at all levels of society.

(Shortform note: While postmodernism has heavily influenced how critical theories study aspects of culture, it doesn’t limit what critical theories study. Instead of being confined to a specific discipline like postmodernism is to philosophy, critical theories can serve as a sort of lens or framework to examine and critique a vast number of different disciplines. Critical theorists have used this general framework to examine topics from film to psychology to economics.)

#2: New Doctrines

Critical theories differ from pure postmodernism in that they establish their own “truths” instead of trying to tear down the concept of truth entirely. Instead of being content with questioning or deconstructing a dominant cultural narrative, they argue using that cultural narrative is morally wrong. Non-dominant cultural narratives—usually the views and experiences of minority groups—therefore must be morally correct truths.

For example, a pure postmodernist deconstructs the femme fatale trope, arguing it represents a dominant narrative of the danger of women in control of their sexuality. They are content just to point this out, though. A critical theory, on the other hand, might go further and argue that using the femme fatale trope is morally wrong because it enforces this dominant narrative. Therefore, the critical theory suggests people shouldn’t put femme fatales in fiction.

(Shortform note: While the concept of truth changed massively during the development into and out of postmodernism, one component remained consistent: an emphasis on the individual. Liberalism, modernism, postmodernism, and critical theories alike all place individual perceptions at the center of what it means for something to be true—whether those perceptions are the “empirical evidence” behind science or the “lived experiences” behind critical theories. This contrasts with more community-focused philosophies like Ubuntu or communitarianism, which argue the world can be understood only through the lens of different communities of people.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Helen Pluckrose and James Lindsay's "Cynical Theories" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Cynical Theories summary:

- How and why modern advocacy has gone too far

- How social justice scholarship and activism has become dangerous

- Why freedom of speech and belief in science are more important than ever