This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States" by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

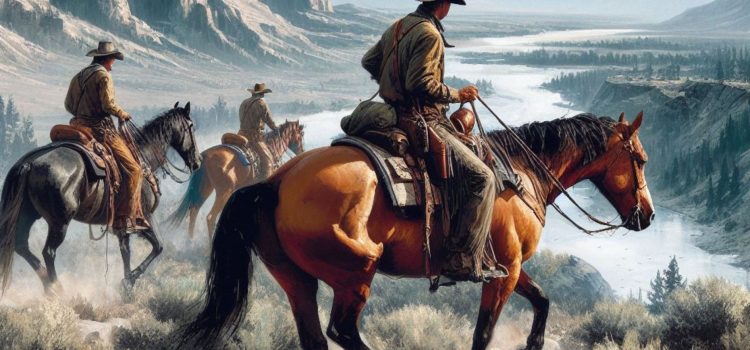

What did the westward expansion of the United States look like? What were its impacts on Native Americans?

The westward expansion of the United States relied on violence towards and removal of Native American nations. An example of this was the Trail of Tears, a forced migration of 16,000 Cherokees where only 50% of the people survived.

Here’s what happened when Europeans moved westward in the Americas.

The Westward Expansion of the United States

In An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, author Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz explains that when the British withdrew from the Americas to focus on colonial exploits in Asia, the colonists won the war for American independence, formally established the United States, and continued the pattern of genocidal violence against Native Americans. In this article, we’ll discuss how the US perpetrated violence against Native Americans during the westward expansion of the United States over the course of its first 100 years.

US Violence Against Native Americans During Westward Expansion

Dunbar-Ortiz says that after the US became an independent nation, it was an immediate priority to expand westward beyond the Appalachian Mountains. (Shortform note: The Appalachian Mountains span nearly 2,000 miles from Alabama in the southern US to Newfoundland and Labrador in northeastern Canada. They served as a natural barrier to westward expansion because they were difficult to traverse; prior to westward expansion, settlers were confined to the east coast region bordering the Atlantic Ocean.)

Dunbar-Ortiz explains that for the purposes of westward expansion, the US government gave itself the Constitutional right to take ownership of native land via treaties. The first presidents sent the newly minted US Army into those regions to terrorize indigenous peoples, confiscate their land, and coerce native leaders into signing treaties that enabled the US government to sell that land for profit. Settler militias also continued their pattern of violence against Native Americans to usurp their lands independently of the government. For example, squatters led by John Sevier expanded into present-day East Tennessee by waging a ruthless total war until the Cherokee ceded land in the Treaty of the Holston.

(Shortform note: As Dunbar-Ortiz says, treaties often followed warfare, but in other cases, US negotiators threatened to wage war if native peoples wouldn’t cede their lands. These threats weren’t empty, but they were reluctant; Native Americans used this fact to negotiate for greater resources and privileges in exchange for peace. Since settlers couldn’t make legal treaties, they vied for land by force and hoped the US would back them up. This was the case, for example, following Sevier’s war against the Cherokee: Governor William Blount negotiated the Treaty of the Holston, under which the Cherokee ceded some land but were empowered to restrict further settlement of remaining lands. However, the US didn’t hold up their end of that bargain.)

Once the US secured lands just beyond the Appalachian region, it decided to expand even further westward. The first step in this process was the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France; the second step was the annexation of Mexican lands after Mexico gained its independence from Spain. In both cases, the US government endeavored to remove indigenous peoples from newly acquired lands so that these regions could be settled by US citizens.

(Shortform note: With the purchase of the Louisiana Territory, the US doubled its landbase, acquiring over 800,000 square miles spanning 14 present-day states between North and South Dakota and Louisiana. The US acquired slightly less land from Mexico—only 525,000 square miles, which spans nine present-day states. Altogether, these lands constitute about 35% of the US’s total landbase.)

Andrew Jackson carried out much of the work in the Louisiana region. As a general, he led a ruthless total war against the Muscogee nation, which he then forced to sign a treaty agreeing to give up their lands and move to designated Indian territory (land set aside by the US government for Native American survivors to live on). According to Dunbar-Ortiz, these events launched Jackson to national prominence and eventually to the presidency, where his administration oversaw the signing of almost 90 treaties laying claim to indigenous lands. This pattern culminated in the Trail of Tears—the forced migration of 16,000 Cherokee (half of whom died during the march) from their homelands to Indian territory.

(Shortform note: The war Andrew Jackson waged against the Muscogee is known as the Creek War. Jackson’s victory in the war destroyed native resistance efforts in the region, and the ceded land amounted to 23 million acres across present-day Alabama and Georgia. Other experts note that it wasn’t Jackson’s idea to remove the Muscogee to Indian territory; it was Thomas Jefferson’s a decade earlier. But as president, Jackson did accelerate the US’s program of Indian removal—he used treaties to usurp 25 million acres across the South, which enabled white settlers to expand slavery. The Trail of Tears was particularly brutal, but experts disagree about how many Cherokee died along the way; some sources claim 4,000 fatalities.)

Dunbar-Ortiz explains that the US viewed newly independent Mexico as an unstable indigenous nation whose lands were destined by God to belong to the US; historians call this belief manifest destiny. A territory could only become a state once there were more Anglo-American settlers than Native Americans living there—so the US was motivated to wipe out indigenous Mexican populations or remove them to Indian territory. As with earlier westward expansion, the US accomplished this via military occupation and progressive settlement of Mexican territories (the Mexican-American War). The genocide escalated during the Gold Rush (an influx of gold miners to California)—more than 100,000 native people were killed in 25 years.

(Shortform note: Experts note that while the US’s victory in the Mexican-American War didn’t bode well for indigenous peoples, a Mexican victory wouldn’t have, either—both nations had genocidal intentions for Native Americans. As Dunbar-Ortiz notes, the genocide of western Native Americans was escalated by the Californian Gold Rush; experts say this and other gold rushes also harmed native peoples via ecological damage, which resulted in reduced resources and ill health. Experts also explain that manifest destiny didn’t end with the Mexican-American War; the US used this concept to justify its annexation of Hawaii and Alaska, and in 2020, President Donald Trump applied it to the exploration and potential colonization of outer space.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz's "An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States summary:

- A retelling of US history from a Native American perspective

- What led Europe to colonize the Americas

- How patterns of genocide and resistance have played out over the course of US history