This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Grant" by Ron Chernow. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Was Ulysses S. Grant an alcoholic? How did Grant overcome his trouble with alcohol use?

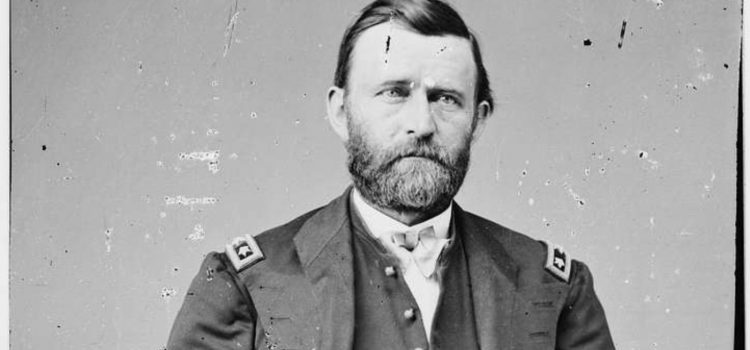

Many historical accounts suggest Grant drank recklessly and was controlled by intemperate desires during his military career and presidency. But, according to Grant by Ron Chernow, Grant fought valiantly against his tendency toward unhealthy alcohol use and attained victory over this tendency in his final years.

Let’s examine Chernow’s account of Grant’s alcohol use.

The Roots of Grant’s Alcohol Misuse

Was Ulysses S. Grant an alcoholic? When did he start drinking? According to Chernow, Grant’s struggles with alcohol misuse had deep roots in his family and his early military service. Chernow points out that, per correspondence from Grant’s father, Jesse Root Grant, Grant’s grandfather misused alcohol. Because alcohol misuse is partially hereditary, this suggests Grant might have been genetically predisposed to unhealthy drinking patterns.

(Shortform note: Though a familial history of Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) doesn’t guarantee someone will develop unhealthy drinking habits, it makes it substantially more likely—50% of individuals whose families have widespread alcohol misuse are themselves disposed toward AUD, even though only 6% of US adults have AUD.)

Chernow contends that the first indications of Grant’s struggles with alcohol misuse occurred during his time as an officer in the Mexican-American War. According to Grant’s friend, Richard Dawson, Grant drank heavily after the war, to the point that his drinking had visibly impacted his health. But, Chernow writes, Grant’s struggles were amplified in 1854 when he was stationed at Fort Humboldt—an isolated fort in Northern California, where Grant was separated from his family and grew increasingly depressed. Interviews with Grant’s fellow soldiers reveal that, during this time, Grant frequently drank to the point of sickness.

However, Grant’s unhealthy alcohol use reached a new low in April 1854. Chernow writes that Grant’s commanding officer—Colonel Robert Buchanan—admonished Grant after a severe drinking incident, telling Grant that he would compel Grant’s resignation if it occurred again. Then, when Grant later turned up intoxicated at his company’s pay table, Colonel Buchanan allegedly told Grant he could resign or face a court-martial and possible dishonorable discharge. Thus, on April 11, 1854, Grant resigned his post as captain, leaving the military.

| Alcohol Use in the US Military Grant’s struggle with alcohol abuse reflects a widespread trend in the US military that persists today. According to a 2017 study from the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), military members drink alcohol more frequently than members of any other profession—they consume alcohol an average of 130 days per year and indulge in binge drinking an average of 41 days per year. Experts point out that this alcohol use is typically a means for soldiers to cope with the stress of combat. According to Bessel van der Kolk, the author of The Body Keeps the Score, combat experience often traumatizes soldiers, leading them to constantly replay these experiences in their heads and inadvertently retraumatize themselves. In Grant’s case, it’s possible that his experience as a combatant in the Mexican-American War caused him to undergo this cyclical trauma as well. For this reason, soldiers like Grant often distract themselves from these flashbacks through alcohol or drug abuse. Moreover, the stigma against getting help for substance abuse in the military often makes it difficult for soldiers to seek treatment. And although the US military does offer treatment for active duty soldiers suffering from substance abuse, the possibility of disciplinary action for voluntarily seeking treatment deters many soldiers from doing so. |

Grant’s Recognition of His Addiction

Although Grant’s unhealthy alcohol use had debilitating effects, Chernow argues that Grant wasn’t the passive victim of his addiction, but actively recognized it and fought against it. To show as much, Chernow points to Grant’s early membership in temperance movements and his later reliance on his aide in the Civil War, John Rawlins, to enforce his sobriety pledge.

As Chernow relates, Grant joined the Sons of Temperance—a national brotherhood advocating abstinence from alcohol—in the late 1840s, even organizing his own division in Sackets Harbor, where he was stationed. In addition to taking a vow of sobriety, Grant’s membership required him to wear a white sash publicly showing his association with the temperance movement. According to an interview with a friend, Grant joined the Sons of Temperance because he was convinced that abstinence was the only protection from his tendency to misuse alcohol.

In addition to joining the temperance movement as a young soldier, Grant also recognized his struggles with unhealthy alcohol use as a colonel at the beginning of the Civil War. Chernow writes that in 1861, Grant appointed John Rawlins—a steadfast advocate of temperance—as his chief of staff, and allowed Rawlins to enforce Grant’s vow of sobriety until the war ended. By making this pledge to Rawlins, Grant showed a willingness to confront his alcohol misuse rather than downplaying its significance.

Grant’s Eventual Victory Over Unhealthy Alcohol Use

Despite Grant’s lifelong struggles with alcohol misuse, Chernow maintains that Grant conquered his addiction during and after the Presidency, before his death in 1885.

Chernow points out that, during Grant’s Presidency, Grant was known to refuse any alcohol at state dinners, and on New Year’s Day, he ordered coffee to be served in lieu of alcohol. Further, according to correspondence from Admiral Daniel Ammen (one of Grant’s closest friends), Ammen never once witnessed Grant inebriated during his eight years as President. And more generally, Chernow argues that the lack of credible accusations of binge drinking during Grant’s tenure as President suggests Grant had remained sober.

(Shortform note: The nature of the Presidency may actually have helped Grant stay sober. In Party Like a President, Brian Abrams argues that two considerations generally deter Presidents from drinking while in office. First, they’re constantly being watched, which provides a powerful incentive to remain sober. Second, they simply lack the time to drink recreationally since their schedules are overloaded. Nevertheless, some Presidents still succumb to temptation—Richard Nixon, for example, famously got too drunk to speak with the British Prime Minister about tensions in the Middle East, leaving Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to cover for him.)

As evidence that Grant continued to conquer his unhealthy alcohol use post-presidency, Chernow points to Grant’s renewed association with temperance movements. In 1880, Grant reportedly met with temperance advocates in Florida, formally declaring his belief that alcohol was the root of evils like poverty and crime. However, the strongest evidence that Grant stayed sober stems from his personal butler, ex-slave Harrison Terrell. According to newspaper interviews with Terrell, who likely spent more time with Grant than anyone but Grant’s wife, Grant exclusively drank in moderation later in life.

(Shortform note: Grant’s decision to drink in moderation departs from the advice of popular Alcoholics Anonymous 12-step plans, which often view total abstinence as the goal for people recovering from AUD. According to one study, people with AUD who set a goal of total abstinence are less likely to relapse (10%) than those who set a goal of moderate consumption (50%). However, other experts argue that drinking in moderation has advantages over pursuing total abstinence, as you’re less likely to have counterproductive shameful thoughts after an occasional drink. In any case, if, as Chernow suggests, Grant made voluntary and lasting positive changes to his lifestyle regarding alcohol, he meets the modern standard of recovery.)

Taken together, Chernow argues, these pieces of evidence indicate that Grant overcame his addiction toward the end of his life. And in Chernow’s assessment, for the man who had conquered the Confederates and reunited the country, the victory over unhealthy drinking might have been Grant’s greatest victory of all.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Ron Chernow's "Grant" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Grant summary:

- A biography of Ulysses S. Grant that paints him in a new light

- Grant's role in the Civil War and as president of the United States

- How Grant fought valiantly against alcohol addiction