This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Leonardo da Vinci" by Walter Isaacson. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

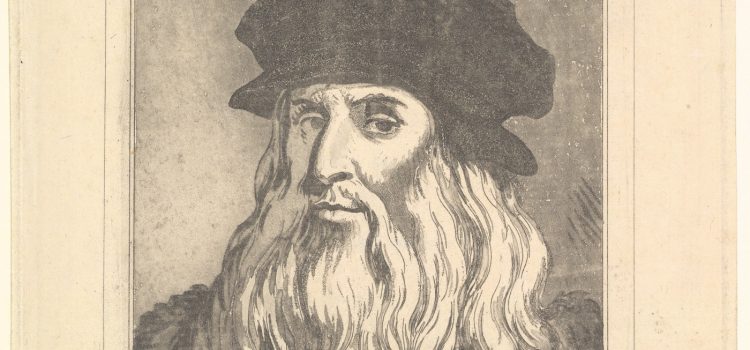

Was Leonardo da Vinci a scientist? Why was Leonardo interested in science?

Unlike other Renaissance intellectuals, Leonardo da Vinci didn’t study the classics. Instead, he based his education on scientific methodologies such as experiments and observations.

Check out why Leonardo da Vinci is technically defined as a scientist, according to his biography by Walter Isaacson.

da Vinci and Science

Leonardo was different from other Renaissance intellectuals because he didn’t base his learning on examining the classics since he couldn’t speak Latin or Greek (although he tried, unsuccessfully, to learn Latin). Isaacson explains that, instead, Leonardo learned by making observations, carrying out experiments, and refining his insights.

Was Leonardo da Vinci a scientist? Isaacson explains that Leonardo became a precursor of modern scientists in many ways:

- He made observations, identified patterns, and conducted experiments to test his ideas. Before drawing conclusions, he conducted further experiments under different conditions so he could be sure his results were valid (an early version of the scientific method).

- He was systematic in his observations. He listed details of an object or scene, then observed one detail closely and committed it to memory before continuing to the next.

- He supported his observations and experiments with theory, but he wasn’t afraid to question accepted theories.

- He didn’t limit his curiosity to specific areas—he made connections across different subjects, using analogies to show the patterns he discovered. For example, while learning to paint perfect curls, he also learned about the movement of water.

(Shortform note: At the basis of Leonardo’s scientific insights was his ability to observe, a learnable skill—except it might be impossible for most people to learn to observe like Leonardo. Scientists are currently working on sequencing Leonardo’s genome to see whether his vision or other senses were genetically different and predisposed to detailed observation.)

Leonardo’s Notebooks

The best testament to Leonardo’s self-directed learning is the notebooks he systematically kept, starting in the 1480s. The practice of keeping a notebook was popular during the Renaissance, but Isaacson argues that no one amassed such extensive and diverse material as Leonardo. (Shortform note: This digitized fragment of one of his notebooks shows some of the variety in his notes. The front page (recto) contains detailed notes on hydrology and hydromechanics, while the back (verso) has drawings he made while dissecting an ox.)

Some of the themes that filled his notebooks include:

- Interesting vignettes he encountered around town

- Sketches and ideas for future paintings, innovative musical instruments, and the theater

- Questions he wanted to investigate, such as “what yawning is”

- Engineering mechanisms, both real and imagined

- Outlines and drafts of treatises on arts and science that he never finished or published

- Calculations and sketches showing how light and shade work from different angles

- Names of people he wanted to have conversations with or ask questions of

- Books he wanted to borrow or buy

- Everyday notes, such as to-do lists and expenses

(Shortform note: Leonardo collected all his valuable ideas and information in one single notebook—like a bullet journal. However, the modern bullet journal method, as Ryder Carrol describes it, can be a lot more organized. For example, you can decide ahead of time what kind of topics you’ll want to write about and customize your journal to have a section for each topic. This will allow you to keep your anatomy and hydrology studies separate, for example, but might prevent cross-pollination of ideas from happening on the same page.)

Hydrology and Geology

As Isaacson explains, Leonardo’s interest in water was second only to his interest in the human body. He explored how water moved and shaped the earth, and he made it a central part of his art and engineering projects. (Shortform note: His interest in hydrology seems to have started when he saw a flood in his childhood.)

Leonardo made several breakthroughs in this area. He invented goggles, floats, and instruments to measure the current and movement of rivers. Also, Isaacson says Leonardo carried out experiments that prompted important discoveries:

- He learned that you can’t compress water.

- He discovered that vortices appear when water flows past an obstacle.

- He discovered how sea waves work.

- He discovered that erosion was the result of water wearing out riverbanks.

- He discovered that mountains were the result of movements in the crust of the earth.

- He was a pioneer in the study of fossils and fossil traces.

(Shortform note: Some consider Leonardo to be one of the founding fathers of hydrology. He previewed a basic tenet of hydrology when he realized that the amount of water that builds up on mountains each year is the same as the amount that comes down through rivers and rain.)

Astronomy

Leonardo’s curiosity about the earth led him to study its place in the universe. According to Isaacson, Leonardo made many astronomic insights that were ahead of his time:

- The earth is not the center of the universe.

- Gravity keeps the waters attached to the earth.

- The moon doesn’t emit light but rather reflects the light of the sun.

- The sky is blue because the sun illuminates the drops of water present in the air.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Walter Isaacson's "Leonardo da Vinci" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Leonardo da Vinci summary:

- A detailed look into the life, accomplishments, and struggles of Leonardo da Vinci

- Lessons from his life and work that you can apply to your own life

- What set Leonardo apart from other artists at the time