This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Blink" by Malcolm Gladwell. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Have you ever misjudged someone based on superficial qualities, like her clothes, her hair, or even her voice? Appearances often mislead us. This is the Warren Harding error.

Learn why we call this the Warren Harding error, and how to avoid letting surface details keep you from making smart decisions about people.

The History of the Warren Harding Error

The Warren Harding error was made popular by Malcolm Gladwell in the book Blink. This is a cautionary tale about what happens when we’re deceived by appearances.

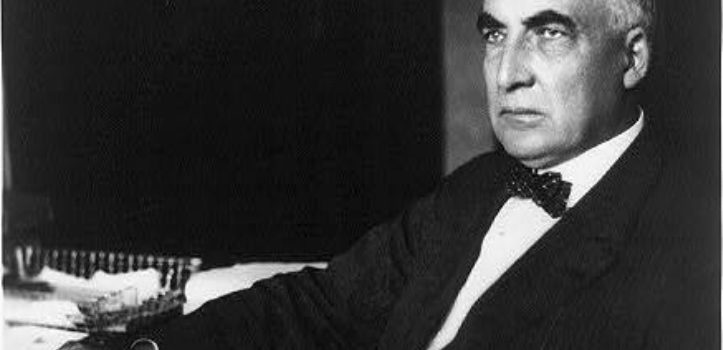

In the early 1920s, Warren Harding looked so presidential that voters were fooled into thinking he’d make a good president. Their unconscious bias for a leader that was handsome and dignified-looking led them astray. This bias interrupted the process of thin-slicing (when you make quick, unconscious decisions), producing an unreliable snap judgment. They based their decision on surface details, voting into office one of the worst presidents in American history. This was the Warren Harding error.

Superficial Thin-Slicing and the Warren Harding Error

Thin-slicing doesn’t always serve us. Sometimes, we make superficial snap judgments.

Usually, thin-slicing helps us get below the surface details of a situation to find deep patterns. But stress, time pressures, and ingrained associations can interrupt this deep dive, leaving us with a snap judgment made on irrelevant surface details.

The Case of Warren Harding

Before he became the 29th president of the United States, Warren Harding had an undistinguished political career. He wasn’t particularly smart, rarely took a stance on (or interest in) political issues, gave vague speeches, and spent much of his time drinking and womanizing.

Still, Harding climbed the political ranks and became president. He’s widely regarded as one of the worst presidents in history. How did he get the position in the first place? The Warren Harding error.

He looked like a president. His distinguished appearance and deep, commanding voice won voters over. They unconsciously believed good-looking people make competent leaders. Harding’s handsomeness triggered associations so powerful they overrode voters’ ability to look below the surface, at his qualifications (or lack thereof). These associations are, by their nature, irrational. This is how the Warren Harding error works, and it can lead to disaster.

Conscious Versus Unconscious Attitudes—Explaining the Warren Harding Error

Sometimes, our snap judgments aren’t only the product but the root of prejudice and discrimination. Our attitudes about race and gender, for instance, operate on two levels.

- Our conscious attitudes are what we choose to believe and how we choose to behave. They are the source of our deliberate decisions.

- Our unconscious attitudes are the unthinking, automatic associations we have regarding race and gender.

The Warren Harding error is the result of unconscious attitudes. We can’t choose our unconscious attitudes. We may not even be aware of them. Our experiences and schooling, the lessons we were taught as children, and the media all form our unconscious attitudes. These attitudes may differ dramatically from our conscious ones.

For example, we would never say that we believe tall people make better leaders than short people. But the numbers indicate that being short is as much of a stumbling block to corporate success as being a woman or a minority. We believe tall people make good leaders, even if we don’t know we believe it. This is an example of the Warren Harding error. Consider these statistics:

- In the U.S., 14.5% of men are six feet tall or taller; 3.9% are six foot two or taller.

- In Fortune 500 companies, 58% of CEOs are six feet tall or taller; 33% are six foot two or taller.

We have an unconscious association between leadership and tallness. We make snap judgments about our leaders based on their height. That stereotype is so strong that it overrides other qualities or considerations. We make the Warren Harding error all the time, and because we do it unconsciously, we don’t know it.

The Disadvantages of Snap Judgments

1) They can’t be explained: When we try to explain how we arrive at an unconscious decision, our explanations are inaccurate and sometimes problematic.

For example, when we attempt to solve insight puzzles (puzzles only the unconscious mind can solve), explaining our strategies hurts us. As soon as we try to elucidate the mystery of our unconscious processes we disable them.

2) The process of thin-slicing can get interrupted: Usually, thin-slicing uncovers the deep truths and relevant details needed to make a wise decision. But stress, time pressures, and biases can interrupt the usually efficient and deep process of thin-slicing, leaving us with snap judgments made on irrelevant surface details.

In order to recognize the power of the unconscious mind’s thin-slicing (and perhaps avoid the Warren Harding error), we need to accept both its light and dark sides:

- Light side: Thin-slicing allows us to judge a person or situation from a first impression. We don’t need long hours or months of study.

- Dark side: Thin-slicing can act on deep-seated biases, leading us disastrously astray.

Can We Change Our Unconscious Attitudes?

Yes, but it takes effort. It’s possible to fight the Warren Harding error, to retrain your implicit assumptions by being aware of them and actively using your conscious mind to counter them.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "Blink" at Shortform . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full Blink summary :

- How you can tell if a marriage will fail, within 3 minutes

- Why your first impressions are usually surprisingly accurate

- The dark side to making first impressions, and how to avoid the,