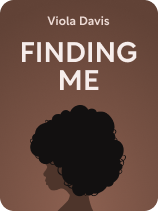

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Finding Me" by Viola Davis. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Do you struggle with self-doubt and feeling unworthy? How did a Hollywood star overcome poverty and trauma to achieve success?

Viola Davis’s memoir Finding Me takes readers on an inspiring journey from her challenging childhood to her rise as an award-winning actress. She shares her experiences with poverty, abuse, and racism while exploring themes of resilience, self-discovery, and the power of dreams.

Keep reading for our overview of Viola Davis’s Finding Me: A Memoir.

Overview of Viola Davis’s Finding Me

Viola Davis’s Finding Me, a memoir published in 2022, recounts her extraordinary journey from the depths of poverty to the heights of Hollywood stardom. In her memoir, Davis explains how acting served as a driving force in her life and a means to self-realization, and she writes candidly about her resilience in the face of poverty, abuse, and racial discrimination. Through her story, Davis addresses broader themes of generational trauma, racism, perseverance, and the challenge of learning self-love in a world that doesn’t always love you back.

Davis is well-known for her work in film, television, and theater. She’s received critical acclaim for her performances in The Help (2011), Doubt (2008), How To Get Away With Murder (2014-2020), and Fences (2016). Davis is the first Black woman to achieve the “Triple Crown of Acting” with an Academy Award, an Emmy, and two Tony Awards. Beyond her acting career, Davis, together with her husband Julius Tennon, runs JuVee Productions, a Los Angeles-based company dedicated to creating and producing stories across film, TV, theater, and digital platforms that showcase a wide range of human experiences from diverse voices.

In this overview, we’ll walk you through a chronological overview of Davis’s life, highlighting the major themes that permeate the memoir. We’ll supplement the story of Davis’s life with historical context and additional details about her life not included in the memoir. We’ll also discuss Davis’s impact on the broader discourse of diversity in Hollywood and the media.

A Journey to Find Self-Love

According to Davis, there’s a representative story from her childhood that’s shaped much of her life. When she was in third grade, she would race home from school every day chased by a group of mostly white boys. The boys would run after her, throwing bricks and stones, calling her the n-word, and telling her how ugly she was. When Viola told her mother, her mom said that Viola had to stop running and stand up for herself. And the next day, she did.

But, as Davis explains, she still sometimes feels like that little girl—always running, trying to fit in, and believing herself unworthy. According to Davis, her life’s work has been about learning to love herself and acknowledging the beauty and strength of her younger self.

According to Davis, her life has been a process of learning how to love herself and accept all of who she is—the successful woman she’s become and the scared and hurt little girl she once was, knowing that who she is now is in large part thanks to the resilience and courage of her younger self.

We’ll describe Davis’s childhood, which was marked by deep love, but also traumatic poverty and abuse.

Childhood

Davis was born on August 11, 1965 in St. Matthews, South Carolina in the same one-room house where her maternal grandparents had lived when they worked as sharecroppers on a plantation. Davis’s mother, born Mae Alice but known to Davis as MaMama, was the oldest of 18 children, only 11 of whom survived to adulthood. Davis’s father, Dan Davis, was also born in St. Matthews, but he ran away from home at 15 before finding work as a horse groomer. Neither of Davis’s parents continued their education past middle school, and Davis suspects her father stopped attending school as early as second grade.

Davis’s parents married young. Their first child, John Henry, was born when Mae Alice was only 15. The couple went on to have five more children: Dianne, Anita, Deloris, Viola, and Danielle. Davis recounts that her father was an alcoholic, unfaithful, and often abusive to his wife and six children. However, Davis’s mother and father remained together until her father’s death from pancreatic cancer in 2006. Davis acknowledges that despite her parents’ flaws and the trauma of her childhood, she learned how to navigate the world from them, and she always knew both her parents loved her deeply.

When Davis was still a baby, her family moved from St. Matthews to Central Falls, Rhode Island, in part because it was home to two of the biggest racetracks in the country—Lincoln Downs and Narragansett Racetrack—where her father hoped to get a job grooming horses.

Davis describes her family growing up as poorer than poor. She explains that their first apartment was nice enough when they first moved, but when the building was condemned it became infested with rats, and the family sometimes went without heat, gas, or hot water. There were also sporadic fires due to faulty wiring in the building. Davis’s family depended on food stamps and the charity of a local grocer to feed themselves, and the girls stole occasionally when necessary.

According to Davis, her parents tried to infuse joy and ritual into their children’s lives whenever possible. However, when Davis describes her time in Central Falls, she says she mostly remembers feeling shame. She explains how the burden of racism and generational trauma, combined with a struggle to meet basic needs, didn’t allow her time or space to think of anything beyond her basic survival. Because of these experiences, Davis internalized the idea that she was somehow bad and didn’t deserve anything more than she had—messages that had a lasting impact on her life, emotional well-being, and future relationships.

According to Davis, her oldest sister Dianne was the one who inspired her to dream bigger than what she knew. When Davis was only five, her sister told her that if she wanted something different for herself, she needed to decide what she wanted to be and then work hard to get there.

The Dream

Davis says she figured out what she wanted to be when she was about nine years old. One night, while watching TV, Davis saw Cicely Tyson performing in The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman. Davis had never seen a dark-skinned actor before—someone that looked like her. It was then that Davis knew she wanted to be an actor.

Not long after, Davis had her first performance for a skit competition hosted by Central Falls Parks & Recreation. She and her sisters wrote an original skit called “The Life Saver Show,” inspired by Monty Hall’s Let’s Make a Deal. The sisters rehearsed endlessly and ended up winning first prize. Davis recalls how proud and excited they all were, as if their winning was proof that they really mattered.

According to Davis, acting was more than something she enjoyed doing. If she became successful, acting could be a way to build a more stable life for herself. But she explains that the process of becoming a character was also healing—a way to use her craft to quietly work through personal issues. Acting became Davis’s path to not only professional success but also personal healing, acceptance, and a sense of self-worth.

Early Career

Davis became committed to becoming an actor, taking advantage of every opportunity she could to pursue her dream career.We’ll describe the early years of Davis’s acting career.

Mentorship

When Davis was 14, she got involved with Upward Bound, a college preparatory program for underserved high school students. She participated in a six-week academic summer program in which she lived on a college campus and took drama as an extracurricular. There she met Ron Stetson, an actor and instructor at Upward Bound, who not only taught Davis the fundamentals of acting but also made her believe that she was a true artist, both capable and worthy of success. Stetson provided Davis, and other students, a space to be themselves where they were fully accepted and supported.

Davis expresses gratitude for Stetson and the other adults in her life who pushed her to take advantage of opportunities to nurture and showcase her talent. For example, her high school science teacher encouraged Davis to apply for the Arts Recognition and Talent Search Competition (ARTS), a national competition recognizing and supporting young artists in the visual, literary, and performing arts. Successful applicants won an all-expenses-paid trip to Miami, Florida.

With support from her teacher and Upward Bound advisor, Davis applied and, to her surprise, won a spot. Though Davis felt out of place at the competition in Miami, her talent was noted by many of the attendees, and she was awarded the title of “Promising Young Artist.”

Rhode Island College

After graduating from high school, Davis received a full scholarship to attend Rhode Island College. Despite her early achievements, Davis still doubted that she could make a living as an actress and took English and education classes instead. Working multiple jobs and still struggling to feed herself, Davis felt lost and out of place. She explains that she fell into a deep depression that lasted until she finally made the decision to switch her major to theater and really give acting a shot. By the time she graduated in 1988, Davis was being recruited for master’s programs in theater all over the country.

Davis notes that, even as others continued to recognize her success, she still felt trapped by the self-doubt and fear that had plagued her childhood. She explains that others’ affirmations of her talent were a poor replacement for true self-love, which she still lacked.

First Paid Acting Job

After graduating from Rhode Island College, Davis continued to pursue acting. She received a full scholarship to participate in a six-week summer program at Circle in the Square Theatre School, which offers programs and training for aspiring actors, directors, and playwrights. Here, she was mentored by Alan Langdon, whom she calls one of her greatest teachers. Davis took whatever jobs she could get to pay for her housing and living expenses. She worked in factories, as a telemarketer, and handing out flyers in Times Square for a friend’s play. After that summer in New York, Davis got her first professional acting job with Trinity Repertory Company, a renowned regional theater in Rhode Island.

The Juilliard School

But Davis wanted to land bigger roles. Following advice from a friend, she decided to apply to Juilliard, a renowned school for performing arts. (She only applied to one school because she could only afford one application fee.) She took the train from Rhode Island to New York, completed a brief 45-minute audition, and was back in Rhode Island the same day to be on time for her evening performance at Trinity Rep. Davis says she knew as soon as her audition was over that she would be accepted to Juilliard.

Davis attended Juilliard from 1989 to 1993. In reflecting on her time at the prestigious institution, Davis emphasizes how challenging it was, not only because of the rigorous coursework and time commitment, but also because Juilliard’s standards for acting were based on white cultural norms. Davis explains that while she was asked to stretch in new ways as an actor, she was also asked to diminish her blackness, to mold herself into the ideal of a white actor. According to Davis, Juilliard only taught a Eurocentric theater canon; any work outside of that scope wasn’t considered worthy of consideration. While earlier experiences of racism had made Davis feel small, her experience at Juilliard made her angry.

Davis was looking for a different kind of experience. She wrote an essay about her experience as a Black woman at Juilliard and earned a scholarship to pursue a professional development opportunity outside of her normal coursework. The summer between her sophomore and junior year, Davis traveled to Gambia with a small group of students to study the dance, music, and folklore of several West African ethnic groups, including the Wolof, Jola, Mandinka, and Sousou.

Davis describes the trip as an awakening. For the first time, Davis saw blackness as something beautiful that should be celebrated. Moreover, as she learned about and practiced the dances and other art forms of West African, she recognized that art didn’t have to be dictated by an enforced and arbitrary standard, but rather could be born out of human experience—the innate desire and need to express oneself. Art, Davis realized, should be an expression of what makes us human.

Upon her return to Juilliard, Davis presented a one-woman performance, which she described as the culmination of everything she’d learned in West Africa. The performance was met with critical acclaim, leading to her recruitment by Mark Schlegel of the J. Michael Bloom Agency. The highly regarded New York talent agency was so impressed that Schlegel offered her a contract even before she had graduated from Juilliard.

Life as a Working Actor

However, even after being booked by a talent agency, Davis’s career didn’t take off. She struggled to get auditions and book parts. Davis reflects that many successful actors talk about not compromising their values, but when you’re struggling to make rent, you don’t always have a choice in the roles you take. She explains that it’s a privilege to be able to choose the parts you play.

Moreover, Davis was coming up against the interconnected forces of racism, colorism, and sexism. The few casting directors who were casting for roles for women of color were looking for “light-skinned” women or women who were more racially ambiguous. More often than not, Davis says, she found herself getting auditions for parts playing crack-addicted mothers or other roles equally steeped in negative racial stereotypes.

Breakout Roles

Davis describes getting her big break when she landed the role of Vera in August Wilson’s Seven Guitars, directed by the renowned Lloyd Richards. The show would travel to Chicago, Boston, San Francisco, and LA before debuting on Broadway the following year.

The show premiered on Broadway on March 28, 1996, and many of Davis’s idols attended, including actresses like Halle Berry and Angela Bassett. According to Davis, her opening performance at the Walter Kerr Theatre was everything she had dreamed of when she first imagined becoming an actress—standing ovations, flowers, and fans waiting at the stage door. Davis’s parents were in the audience on opening night, and Davis could see the pride on their faces. Davis’s performance as Vera also earned her a Tony nomination. Though she wouldn’t win her first Tony for a few years, the nomination gave her further validation of her talent.

Breaking Into TV and Film

Despite her success, Davis couldn’t seem to break into the world of TV and film, which not only paid better but also provided access to better health insurance, which Davis needed as she struggled with painful fibroids. However, to her own surprise, Davis finally landed a small role as Don Cheadle’s girlfriend in the 1998 film Out of Sight, starring Jennifer Lopez and George Clooney.

Once she’d gotten one film role, more started to come. That same year, Davis booked a role in an HBO movie called The Pentagon Wars (1998). She then got a part in the CBS hospital drama City of Angels. Davis hesitated to take the part, as the pay was only about a third of what most series regulars got paid. City of Angels was one of the first all-Black TV dramas and the network was hesitant to invest too much money in it, but Davis decided to take the gig despite the low pay.

Finding Love

Davis was grateful she took the leap to join the cast because she met her future husband, Julius Tennon, on the set of City of Angels three weeks after moving to LA. He gave her his card, but it took her six weeks to work up the confidence to call.

According to Davis, she became happier and more self-confident after she began dating Tennon. In earlier relationships, Davis had never felt like a priority to the men she dated, but Tennon was caring and attentive and made Davis feel wholly loved.

Davis’s relationship with Tennon also allowed her to become financially stable for the first time in her life. The couple moved in together and were slowly able to save enough money to buy a condo. Davis continued to get consistent work, but often in smaller roles and still as the drug-addicted mother (Antwone Fisher) or a white woman’s best friend (Eat Pray Love), but it was enough to sustain her and help out her parents and sisters whenever she could.

Tennon proposed to Davis in 2002 and the two were married at a small ceremony in LA on July 23, 2003. They celebrated their wedding again at a larger gathering with Davis’s whole family in Rhode Island later that year.

Becoming a Mother

Davis explains that she had always wanted to be a mother, but had long struggled with chronic fibroids. After years of pain and the discovery of an abscessed fallopian tube, Davis decided to have an elective hysterectomy.

However, her hysterectomy didn’t stop Davis from fulfilling her dream of motherhood. She and Tennon adopted a baby girl, Genesis, in 2011.

Making It

Davis explains that throughout her career, she was consistently offered roles that were underdeveloped—women who were simply caricatures, stereotypes, or lacking in depth. Therefore, Davis took it upon herself to inject these roles with as much humanity as she could, demonstrating her commitment to bringing authentic, multidimensional characters to life, despite the limitations of the roles she was offered.

At the age of 42, Davis was cast in the relatively minor role of Mrs. Miller in the 2008 film Doubt, starring Meryl Streep, Amy Adams, and Philip Seymour Hoffman. Davis’s portrayal of Mrs. Miller, a mother caught in a difficult moral and personal dilemma, received critical acclaim and showcased her ability to convey profound emotional depth even with minimal screen time. A few years later, Davis was cast as Aibileen Clark, a 1960s housemaid, in the 2011 film The Help. Though many criticized the movie for perpetuating racial stereotypes, Davis’s performance was celebrated for the nuance and humanity she brought to the role. Her performance earned her several nominations and awards, including an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress.

Davis’s career took a monumental turn when she was cast as Annalise Keating in the TV drama How to Get Away With Murder (2014-2020). This role provided Davis an unparalleled chance to portray a complex, brilliant, and flawed black woman, showcasing her acting depth and earning her widespread acclaim. Notably, she made history as the first Black woman to win a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series. The show’s success and Davis’s powerful performance significantly elevated her profile in Hollywood, opening doors to more diverse and complex roles.

On a personal level, playing Annalise catalyzed Davis’s journey towards self-love. The character’s complexities, often absent in Black female roles on TV, empowered Davis to challenge internalized societal norms about Black women. In a significant on-screen moment, Davis removed Annalise’s wig and makeup, embracing her natural appearance—a powerful rejection of Hollywood’s limited beauty standards. In portraying Annalise’s strength and emotional depth, Davis explains how she was also able to celebrate her authentic self, her strengths, and her vulnerabilities.

Paving the Way for Others

According to Davis, her career has never just been about her own success. Davis’s journey through the entertainment industry has been marked by numerous obstacles, many stemming from systemic racism and sexism.

Driven by her personal experiences, Davis has committed herself to challenging these biases. She consciously pursues complex and diverse roles that defy stereotypes, presenting a more authentic portrayal of Black women’s experiences. Through her work, Davis fights against the discrimination that pervades the industry, striving to uplift diverse narratives from marginalized communities. In partnership with her husband, Davis also founded JuVee Productions, a production company that seeks out and develops projects that center on marginalized perspectives, amplifying stories that might otherwise be overlooked.

The Healing Power of Self-Love

While Davis is committed to supporting others, she speaks often about the importance of self-love and prioritizing your own wants and needs. Davis candidly reflects on her struggles with self-esteem and feelings of inadequacy rooted in the racism and trauma she experienced, especially as a young child.

Davis emphasizes the significance of setting boundaries, prioritizing self-care, and embracing vulnerability as key components of self-love. She also discusses the importance of therapy and self-reflection in the healing process. She shares how seeking professional help allowed her to confront and heal from both the immediate and long-lasting effects of trauma. Through therapy, Davis gained tools to address the negative patterns and behaviors that stemmed from her traumatic experiences, allowing her to break free from their hold and reclaim her life.

Davis advocates for the idea that true healing begins from within, encouraging readers to embrace their authentic selves and celebrate their unique qualities. Davis writes that liberation comes when you stop seeking validation and approval from external sources and instead find strength and fulfillment in your inherent worth.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Viola Davis's "Finding Me" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Finding Me summary:

- The story of Viola Davis’s rise from the depths of poverty to the heights of Hollywood stardom

- How acting became a beacon of hope for Davis and a path toward self-discovery

- What Davis does beyond her acting career