This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Crucial Accountability" by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, et al.. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What is toxic communication? How does toxic communication first arise in a relationship?

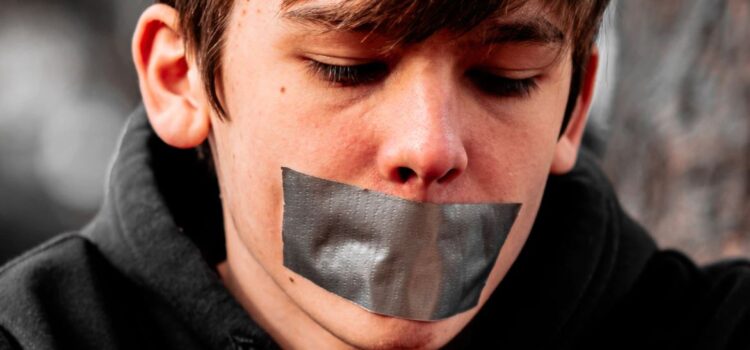

You don’t want to start a fight, but saying nothing might end your relationship. According to the book Crucial Accountability, toxic communication first occurs when people choose to stay silent. Often, people don’t speak up because they either downplay the costs of silence, exaggerate the risk of speaking up, or consider themselves helpless.

Keep reading to learn more about toxic communication and the three reasons people choose to stay silent.

1. Downplaying the Costs of Silence

The authors explain that when we choose to remain silent rather than address an issue, it’s often because we downplay the negative consequences of letting the issue stew. But, silence can lead to a number of bad outcomes, the first of which is that when we stay silent, the original accountability issue will likely persist and possibly get worse.

Furthermore, when we stifle our emotions through silence, we can unintentionally cause more problems, resulting in toxic communication. The authors explain that when we stifle our emotions, we think we’re suffering in silence, but how we really feel is leaking out through our body language, tone of voice, and passive-aggressive behaviors. These passive-aggressive behaviors cause new problems because when others pick up on them, they’ll likely become offended or uneasy. Consequently, they’re likely to behave badly toward you in return, which will continue or even exacerbate the original problem.

| The Four Horsemen of a Relational Apocalypse The authors use original research and insights throughout Crucial Accountability to explain how we can make problems worse by not properly addressing them, but it’s likely that their argument was inspired by John Gottman’s interpersonal communication theory, “The Four Horsemen of a Relational Apocalypse.” Gottman’s theory asserts that there are four primary toxic communication behaviors that lead to relationship termination—contempt, criticism, defensiveness, and stonewalling. This theory is the foundation of the majority of modern interpersonal communication research on relationship maintenance, which is the basis of Crucial Accountability. The authors’ discussion adds to Gottman’s research by addressing each of the four horsemen in different places throughout Crucial Accountability—either encouraging the reader to avoid the behaviors or explaining how we might unintentionally cause the other person to engage in them. In the section above, the authors explain that choosing silence over speaking up can result in passive-aggressive behaviors that leak out unintentionally, such as snarky comments, a rude tone of voice, or rolling your eyes. These behaviors indicate Gottman’s second horseman, contempt, which is a loss of respect for the other person that results from long-simmering, unspoken issues. Gottman makes the same argument as the authors: These contemptuous forms of communication can seriously damage relationships, but they can be avoided by effectively voicing our concerns instead of trying to stifle them. |

2. Exaggerating the Risks of Speaking Up

The authors explain that people also may choose to remain silent because they exaggerate the risks of speaking up—that is, they imagine severe negative consequences that are unlikely to actually materialize. For example, people tend to think that if they bring up an issue, the other person will get angry, resent them or look down on them for speaking their minds.

When we focus on these possible negative outcomes, we often remain silent in order to avoid confrontation.

| How to Avoid Exaggerating the Risks The authors explain that people tend to choose silence because they imagine the worst-case scenario occurring—experts refer to this as catastrophizing. We do this because our brains categorize uncertainty as danger. Psychologists recommend avoiding catastrophizing by first focusing on the present moment rather than the past or future, second considering the facts of the situation (like that the other person is rational and supportive), third thinking about the best and worst-case scenarios, and then finally rationalizing that the most likely situation is somewhere in the gray area between the two. Once you’ve gone through this rationalization process, create a plan that will help you exact the outcome you desire. In the context of Crucial Accountability, that would be determining the key issue, whether or not to address it, cooling your emotions, and then following the steps later on in this guide that will lay out how to best execute the conversation. |

3. Feeling Helpless

The authors explain that a third reason why people choose silence is that they feel helpless, as if bringing up the problem won’t resolve it. This can be especially true when the problem involves difficult people or circumstances. If the people or circumstances seemingly make the problem unsolvable, why bother bringing it up?

People tend to fall into this belief because of failed accountability conversations in the past. If we’ve had past toxic conversations where the other person was resistant or we failed to achieve the desired change, we’re likely to become discouraged, thinking the same outcome will happen every time.

The reality is that we’re not completely helpless when someone refuses to change. In fact, the authors contend that the other person’s inflexibility is likely the result of our ineffective and toxic communication. For example, you may have brought up the conversation in a way that made the other person aggressive, or failed to plan the discussion and identify the correct key issue.

Ultimately, the authors argue that we always have the ability to effectively handle accountability issues. With effective communication, we have much more control over the situation and the other person than most people think. Consequently, feeling helpless is never a sufficient reason to put off having an accountability conversation.

(Shortform note: The authors explain that people tend to consider themselves helpless due to past failed accountability conversations—psychologists call this phenomenon learned helplessness. This mindset often arises due to situations from our childhood. For example, if your parents responded aggressively or ignored you every time you expressed a concern or a desire for change, you will likely enter adulthood with the belief that you are incapable of enacting changes or solving problems in your relationships.)

When the Issue Isn’t Worth Addressing

The authors assert that sometimes, what we perceive as serious accountability issues aren’t actually worth bringing up. Sometimes, what you think is a justified accountability discussion might actually be an unnecessary complaint.

To determine whether or not you’re jumping the gun, consider (1) your intent for the conversation and (2) the consequences the conversation will have on your relationship with the other person.

Your intent should be to maintain a positive and productive relationship with the other person. If your intent for the conversation doesn’t match this definition, or you expect that the consequences of having the discussion won’t achieve this goal, you probably shouldn’t bring up the issue.

- For example, if you’ve had a problem with someone but you don’t expect to ever work with them again, there’s no benefit to bringing up the issue. In this situation, your intention won’t be to improve the relationship—since the relationship won’t continue anyway—and thus the consequences of the conversation don’t justify having the discussion.

| How to Let Go When the Issue Isn’t Justified The authors argue that sometimes what we think is an accountability issue isn’t actually justified, and instead, we need to simply expand our comfort zone; however, they don’t offer advice on how exactly to do this. If we’re not justified in bringing the issue up but are still upset by it, we could end up damaging our relationship with the other person by unintentionally acting out our feelings (as we discussed earlier in this section). In Difficult Conversations, Douglas Stone, Bruce Patton, and Sheila Heen explain that when we find ourselves in one of these situations, we can help get over the issue by: 1. Releasing the negative feelings we have about the situation, the other person, or ourselves. 2. Telling ourselves a different story to explain what happened. For example, your daughter isn’t irresponsible because she dyed her hair, rather she’s expressive, creative, and proud of her identity. 3. Accepting who we were when we got upset and who we are now, after the fact. Being upset by the situation may have been a reaction we couldn’t control; however, after reflecting, we’re in a different mindset and can recognize that our previous impulses weren’t justified. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, et al.'s "Crucial Accountability" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Crucial Accountability summary :

- How to broach sensitive conversations with loved ones and coworkers

- How to prepare for, execute, and follow up on accountability conversations

- How to solve issues while improving your relationships