This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The God Delusion" by Richard Dawkins. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What are theist arguments? What are the main theist arguments, and why don’t they hold up?

Theist arguments present ideas as to why God exists. There’s a whole group of arguments that attempt to do this, and they ignore things like logic and evidence, and depend on abstract ideas.

Read more about theist arguments and why they don’t work.

The Weakness of Other Theist Arguments

Not all theist arguments are based in creationism—although they are all just as flawed and weak as those that are. Let’s look at some of the most famous arguments that theologians have put forward and examine why they fail to achieve their objective.

The Ontological Argument

There is a class of theological arguments known as a priori arguments. These arguments exist independently of observation and are formulated entirely through abstract thought experiments.

The most famous a priori argument for God is known as the ontological argument, first promulgated by the English monk St. Anselm of Canterbury, who lived primarily in the 11th century.

The basic premise of the argument is as follows:

- God is perfect; therefore, nothing can be imagined that is greater than God.

- Such a great being that actually exists must be greater than a being that does not exist, because existence is superior to non-existence.

- If God existed only in the mind (as atheists believe), one could imagine an even greater being—namely, a God that existed in reality, not just in the mind.

- Thus, there is a logical contradiction, because it should be impossible to imagine something greater than God.

- The only way to resolve this contradiction is to accept that God does exist in reality, not just in the mind.

The basic weakness of this theist argument (as was pointed out by 18th-century philosophers like Immanuel Kant and David Hume) is that it proceeds from false premises. The argument falls apart if one does not accept the idea of a perfect God in the first place. And, indeed, atheists do not accept this starting premise. Likewise, the ontological argument suffers from the logical fallacy known as begging the question—in which the premise of an argument already assumes the truth of its conclusion.

Beyond these weaknesses, there is no reason to accept the other pillar of the argument: that an existing God is by definition greater than a non-existent God. By inverting Anselm’s slippery logic, you could argue that a non-existent being is greater than an existing one. A God who overcame the handicap of non-existence to create the universe is surely a greater being than one who created the universe while existing!

The “Beauty by Design” Argument

Another one of the theist arguments is often advanced by theists is the argument from beauty. This states that the most sublime works of human creation, like the plays and sonnets of Shakespeare or the symphonies of Beethoven, are so exquisitely beautiful that they could not have been created by mortal humans. Instead, they could only be products of some divine spark within humans, planted by God.

This is barely an argument at all, as it does not even offer any logic or proof in support of its conclusions. Why does Shakespeare’s Hamlet or Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 require the existence of a deity? Art can be appreciated and celebrated by the religious and non-religious alike; one does not need to accept the premise of a higher power in order to be moved by great artistic works.

This even includes religious art, like the Sistine Chapel ceiling by Michelangelo. An avowed atheist can be struck by the beauty of this work without believing in God. Much European art, in fact, is religious (specifically Christian) in nature, because the Church was the primary patron of the visual arts for most of the medieval and Renaissance periods. Artists like Michelangelo had no choice but to create religious works because they were commissioned to do so by the religious authorities. Left to their own devices, they may well have created secular works of equal greatness.

The Miracle Argument

We often hear of people experiencing religious visions or witnessing miracles. For example, religious people often claim to have heard God speaking to them or to have seen a vision of the Virgin Mary. Before we can accept that these events are miracles—which would be a phenomenally rare occurrence—we must first rule out other explanations that are more likely. The only way we could accept an account of a religious vision or miracle is if rejecting it would be even more implausible than accepting it. This is where a lot theist arguments don’t work.

As it happens, there are multiple more plausible explanations for these so-called miracles. First, the human brain is hardwired to recognize human faces and hear human voices, even where they do not exist. This is most likely an inheritance from evolution. Natural selection would have made it advantageous to be able to quickly identify a potential intruder, even if most of the time this instinct would have generated false negatives (we will cover natural selection in greater detail later in the chapter).

Hallucinations, mass delusions, and simple human error might be rare phenomena—but they are much less rare than direct interventions by God in the physical world. The only reason that we treat hallucinations differently than claims of epiphany is that most people don’t experience genuine auditory or visual hallucinations, but most people do accept the core claims of theistic religion. Religion simply has the numbers on its side.

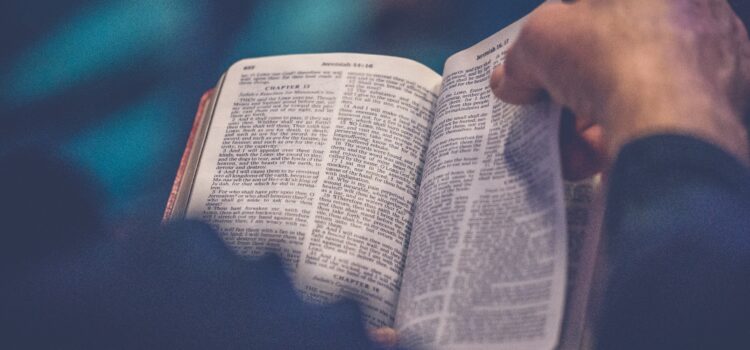

The Argument From Biblical Authority

Many religious people employ the circular logic of appealing to the Bible itself for proof of God’s existence. The Bible is divinely authored, according to this argument, and it says that God exists and regularly intervenes in human affairs. Therefore, there is incontrovertible proof of his existence.

Of course, non-believers don’t accept that the Bible is divinely authored or inspired, so this argument also assumes facts not in evidence. Moreover, the Bible was written and compiled by several different authors, writing centuries after the events they purported to describe.

Thus, the Bible is riddled with inconsistencies and scholars don’t consider it a reliable historical account. For example, the Bible is unclear about whether Jesus was born in Bethlehem or Nazareth. That the Bible is unable to even get the facts straight on where the supposed son of God was born argues strongly against relying upon it as a historical source.

Pascal’s Wager

Pascal’s wager is the last of the theist arguments. The wager, proposed by the French philosopher Blaise Pascal in the 17th century, isn’t an argument that seeks to prove God’s existence, but it does try to make the case that an individual ought to believe in God. The argument goes:

- If you believe in God and he does exist, you are rewarded with an eternity in heaven (according to Christianity at least).

- If you believe in God and he doesn’t exist, you gain nothing but also suffer no penalty.

- Likewise, if you don’t believe in God and he doesn’t exist, you gain nothing but suffer no penalty.

- However, if you don’t believe in God and he does exist, you will suffer eternal torment and damnation.

According to Pascal’s wager, there is no cosmic upside to being an atheist; but there is potentially an enormous downside. Therefore, the only logical thing to do is to believe in God.

However, this thought experiment fails to make an airtight case for belief in God. You can’t be forced to believe something; you either believe it or you don’t. The only thing Pascal’s wager could compel is false belief, pretending to accept the existence of an omnipotent, omniscient God. But wouldn’t this all-seeing, all-knowing deity see through your ruse? Might he then be inclined to punish you further for your attempts to deceive him?

What’s more, how do you know if the God you happen to believe in is the one that really exists? By picking the “wrong” God, you might have damned yourself just as much as by believing in no God at all.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Richard Dawkins's "The God Delusion" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The God Delusion summary :

- Why Dawkins thinks religion has exerted a harmful influence on human society

- How Dawkins concludes that the existence of God is unlikely

- The 3 arguments that challenge the existence of God