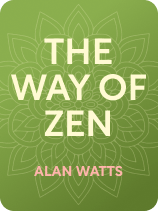

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Way of Zen" by Alan Watts. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Why shouldn’t Zen Buddhism be considered a religion? How is it liberating? How does Zen Buddhism conceive of time?

Though most of us have a passing familiarity with the concept of Zen, few of us really know what “Zen” means or could articulate how Zen Buddhism describes reality and human life. Philosopher Alan Watts explains the major principles and the history of Zen Buddhism in The Way of Zen.

Read on for several The Way of Zen quotes that will give you a taste of the book’s ideas.

The Way of Zen Quotes

First published in 1957, The Way of Zen explains the schools of thought from which Zen originated, breaks down its most foundational principles, and describes how you can experience Zen in your everyday life. (Spoiler alert: Watts thinks that you don’t have to spend your days in meditation or contemplation to make it work!)

We’ve collected five The Way of Zen quotes and provided them along with some context to help you understand what Watts is saying.

“Oddly enough, if we had to decide to decide, we would not be free to decide.”

An idea that’s foundational to Zen comes from the Taoist principle wu-wei, the experience of making decisions naturally and spontaneously. Watts writes that, when you let your mind decide how to act, it moves more naturally and intelligently—not impulsively, but out of the spontaneity of the moment. This leads to the experience of wu-hsin, translated as “no mind,” a kind of “un-self-consciousness” that you can experience when you let your mind work without trying to direct it or interfere with it. You can develop te, or “virtue,” a creative ability that you can only access by acting naturally and spontaneously.

Watts traces this logic a step further and explains that, not only can you act spontaneously, but there’s no other way you can behave. If you realize that even your intentions, purposeful actions, and voluntary decisions arise spontaneously from your natural self (the self that you actually experience, rather than the abstract idea of yourself), then you can stop trying to be spontaneous or worrying that you aren’t.

“If we open our eyes and see clearly, it becomes obvious that there is no other time than this instant and that the past and the future are abstractions without any concrete reality.”

One way that Zen can help change your perspective comes when a Zen understanding of relativity changes your relationship with time. Watts explains that learning to recognize time as relative can help you feel more still and calm no matter what’s happening. When you’re worried about the passage of time, it just seems to pass more quickly. But when you stop trying to hold onto it, its pace seems to slow.

Watts writes that a major idea of Zen is that you don’t have anything except the present moment. He explains that to Zen, the past and future are just abstractions, and the only moment that has any concrete reality is the one you’re living in right now. As long as you don’t label this moment the present—which implies that it’s separate from the past and from the future—then you can be awake and alive to just this moment.

“I have no other self than the totality of things of which I am aware.”

A core idea to Zen’s teachings is the principle of wu-hsin, or “no-mind.” Building on the Taoist philosophy of naturalness, the principle of wu-hsin suggests that, instead of trying to still, empty, or purify your mind, you should let go of your control of the mind itself.

Watts writes that, when you combine wu-hsin, or “no mind,” with wu-nien, or “no thought,” you free your mind to act while thinking, without trying to second-guess or control it. The point of this un-self-consciousness is not to be unaware of what’s happening around you or within you, but to shift your attention away from conscious cognitive processes and toward a spontaneous and creative state. This involves just observing thoughts come and go, without suppressing them, holding onto them, or trying to interfere with them.

According to Watts, Zen became a new school of Buddhism because it took a new and unique view of dhyana, a concept that Watts notes is often but inadequately translated as “meditation.” He explains that dhyana might be better understood as a state of awareness that’s focused on the present and unconstrained by false boundaries between “the knower, the knowing, and the known.” In other words, Zen teaches that when we enter a state of dhyana, we look beyond conventional separations to see the world for what it is.

“To be free from convention is not to spurn it but not to be deceived by it. It is to be able to use it as an instrument instead of being used by it.”

Zen Buddhism is a “way of liberation” from the illusions you believe about the world and yourself. Watts writes that Zen frees you to perceive the world in a more natural way, and you can experience this liberated way of moving through the world when you understand that you’re already enlightened due to your nature as a human being.

The first change that Zen can help you make is to curb your innate desire to constantly improve yourself or your situation. Watts explains that this improvement is often an illusion of dualistic thinking—an illusion we can stop buying into to end the cycle. He writes that we apply the same dualistic (and mistaken) pattern of thinking when we conceive of good and evil or pleasure and pain as opposite states. When you see that not only can one not exist without the other but that you can’t experience one without the other, then you stop striving against inevitable experiences like discomfort, pain, and frustration.

“Zen Buddhism is a way and a view of life which does not belong to any of the formal categories of modern Western thought. It is not religion or philosophy; it is not a psychology or a type of science.”

Watts makes a point of calling Zen a “way of liberation” because it isn’t a religion and isn’t a philosophy, and other writers—including D. T. Suzuki and Carl Jung—have agreed that it doesn’t fit neatly into either of those categories. Suzuki, from whom Watts first learned about Zen, explained that there can’t be a “philosophy” of Zen because “there can’t be a philosophy of suchness,” a Zen term for the true nature of reality that can’t be expressed in language or other forms of abstraction. Instead, Zen is something that you are and something that you do when you express your true nature and engage in disciplined practice.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Alan Watts's "The Way of Zen" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Way of Zen summary:

- The major principles and history of Zen Buddhism

- How to experience Zen in everyday life—without a strict meditation practice

- Why calling Zen a "practice" is a mistake