This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Nudge" by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What is the spotlight effect? How does the spotlight effect relate to social influence?

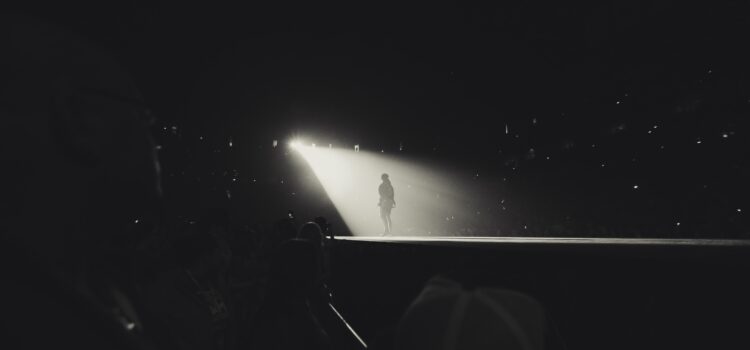

The spotlight effect is the usually mistaken belief that others are watching and judging you. You feel like you’re in the spotlight, and this changes how you behave.

Read more about the spotlight effect and how it alters behavior.

What Is the Spotlight Effect?

Another ingredient in the human compulsion to conform is the spotlight effect: our (largely mistaken) perception that others are (1) paying close attention to us and (2) judging us.

In one experiment about the spotlight effect, researchers had student subjects wear a Barry Manilow t-shirt—after determining that Barry Manilow was the most embarrassing celebrity to advertise on a t-shirt—and fill out a questionnaire alongside fellow students. The researchers then made up an excuse to remove the student from the room and, outside, asked the student to estimate how many of his or her fellow students could identify the person on the t-shirt. The average estimate was just under 50%, but the researchers found the actual number was closer to 20%. (The researchers also had subjects watch the classroom on videotape, and these dispassionate observers estimated around 20% as well). In other words, actually wearing the shirt increased the student’s self-consciousness or the impact of the spotlight effect.

Social Influence

Humans are highly motivated by the behavior of their peers, and choice architects can achieve surprising results simply by framing certain beneficial choices as the social norm.

An experiment conducted in San Marcos, California, illustrates the point. Working with a sample size of 300 households, the researchers informed each household of its energy use over the previous several weeks and also provided the average San Marcos household’s consumption. In the subsequent weeks, the researchers found that the households whose consumption was above the average reduced their consumption. (Unfortunately, they found that social cues work both ways: Households under the average increased their consumption.)

Social influence affects not only what entertainment and politicians we prefer, but also how we spend and invest our money. Sometimes the financial advice of our neighbors can be helpful, but herd thinking in the economy can also result in major problems.

The 2008 financial crisis is a case in point. According to economist Robert Shiller, who was one of the few analysts to predict the crisis, speculative booms—like the one in the housing market that preceded the crash—are largely the product of “social contagion.” That is, people become overly optimistic about a particular investment, which drives up prices. The rise in prices is then covered by the media, and more people begin to invest in that area, attracting more media attention, and so on. In a speculative bubble, prices are a product of social consensus rather than actual value. (Shortform note: Read more about the 2008 financial crisis in our summary of The Big Short here.)

Libertarian Paternalism

Given Humans’ innate propensity to make poor choices, whether through cognitive bias or social conformity or animal desire, are good decisions simply beyond us? Is there any way, other than severely restricting the number of choices available to us, that public and private entities can help us help ourselves?

Thaler and Sunstein’s answer is the embrace of a new movement: libertarian paternalism.

Libertarian paternalism seeks to preserve liberty—that is, our freedom to do what we like, as long as it doesn’t infringe on another’s opportunity to do the same—while using techniques suggested by behavioral economics and psychology to point us in the most beneficial direction. In a libertarian paternalistic world, the public and private entities that present us with choices —“choice architects,” in Thaler and Sunstein’s terminology—use subtle strategies to push us toward the “right” choices. These “right” choices are the ones we would make for ourselves if we weren’t susceptible to cognitive bias, temptation, or social influence.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein's "Nudge" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Nudge summary :

- Why subtle changes, like switching the order of two choices, can dramatically change your response

- How to increase the organ donation rate by over 50% through one simple change

- The best way for society to balance individual freedom with social welfare