This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Make It Stick" by Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger III, Mark A. McDaniel. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

How do we learn? What are the processes that allow us to encode knowledge into the brain?

Psychologists conceptualize three stages of learning: 1) encoding, 2) consolidation, and 3) retrieval. At the encoding stage, the brain creates mental representations of the information. Then, it consolidates it by transferring it from short-term to long-term memory. Finally, it cements the knowledge to make it available for retrieval.

Learn more about the psychology of learning, what happens at each stage, and how new information is embedded in the brain at the cellular level.

The Three Stages of Learning

1) Encoding: When you learn something new, your brain encodes it by creating memory traces, which are mental representations of the information. The memory traces are stored in the short-term memory, as if your brain were taking notes in a notebook.

2) Consolidation: The memory traces in your short-term memory are still somewhat pliable, so the consolidation process strengthens the knowledge and transfers it to your long-term memory. Scientists believe that during consolidation, your brain rehashes the lesson, fleshes out gaps in the memory traces, and connects the new information to your prior knowledge and experiences. This process requires hours or days, and experts believe sleep aids in consolidation. (Shortform note: Read more about how sleep improves learning in our summary of Why We Sleep.)

Compare consolidation to revising an essay: Your first draft is rough but gets the general ideas down, like the encoding process. Then, as you edit the paper, you fill in the gaps and it becomes more refined. Finally, after you put it away for a while and then come back to write the final draft, your thoughts clarify and you gain a better sense of what your thesis is and how to illustrate it to readers by drawing links to information they already know.

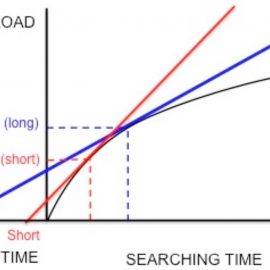

3) Retrieval: The purpose of learning is to have that knowledge on hand when you need it—whether you’re solving a math problem or speaking a second language. This requires that you commit the information to your long-term memory, and that you create retrieval cues, which connect the new information to your prior knowledge and experiences.

For example, a Marine learning to parachute in jump school must learn how to hit the ground to minimize injury. First, trainees practice falling from a standing position and get corrective feedback on their positioning. Then, they do the same from two feet off the ground. The Marines apply their knowledge to each progressive level of difficulty as they fall from higher and higher off the ground, incorporating more complicated skills at each level.

Each time you practice, you create a new experience, creating a new cue and further cementing that knowledge in your memory. Retrieval cues help you pull up the information in different situations, making the difference between retaining static facts and being able to use the knowledge when a situation calls for it. The more retrieval cues you have, the more readily you can recall information.

Additionally, when you retrieve knowledge from your memory, you trigger reconsolidation, which further bolsters the memory traces and allows you to form even more connections with information you’ve learned since the knowledge was first consolidated.

Your Brain Is Built for Learning

Learning is a lifelong process. Your brain is designed with plasticity and flexibility that allow you to learn and adapt—for example, the way a blind person’s brain heightens her other senses to compensate for her lack of vision.

You’re born with billions of nerve cells called neurons. Your neurons sprout axons, which stretch like branches to connect with other neurons’ receiving ports, called dendrites. When an axon connects with a dendrite, this connection is called a synapse. Synapses are the circuits through which signals and information travel.

Some axons have a waxy coating called myelin, which acts like the plastic that’s wrapped around the wires on electrical cords. Scientists believe that the more you practice a skill, the thicker the myelin coating on the associated axons—and the thicker the myelin, the stronger and faster the signals to perform that skill. This explains how, after thousands of hours of practice, professional basketball players’ dribbling synapses are so heavily myelinated that they can do it reflexively.

When skills become habit, experts believe your brain links the motor skill with the cognitive action so that they fire off simultaneously and subconsciously, rather than through a conscious (albeit rapid) thought process. The habit is then recoded and stored deep in the brain, in the basal ganglia, where eye movements and other subconscious acts originate. Many people experience this in the way they type on a computer keyboard without thinking about what their fingers are doing.

Your brain continues to make new neurons your entire life. This process is called neurogenesis, and it happens in the hippocampus—the same area that consolidates new information and memories. Research is ongoing about the connection between neurogenesis and learning and memory, but there is evidence that when you make connections between different types of information, it stimulates neurogenesis.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger III, Mark A. McDaniel's "Make It Stick" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Make It Stick summary :

- How to understand and remember what you learn

- How a little forgetting helps you remember

- Why you’re not a good judge of how much you know