This is a free excerpt from one of Shortform’s Articles. We give you all the important information you need to know about current events and more.

Don't miss out on the whole story. Sign up for a free trial here .

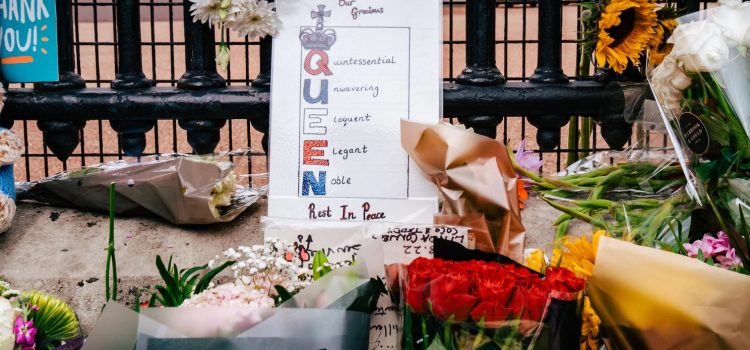

What does the future of the monarchy look like after the passing of Queen Elizabeth II? Is there still a place for the monarchy in Great Britain?

There are some who say that the monarchy—a relic of an imperial era—feels anachronistic. However, the monarchy still serves an important ceremonial and cultural purpose.

Here’s why the future of the monarchy is secure.

Does the Monarchy Still Have a Role?

The passing of Queen Elizabeth II marked the end of an era—one in which the institution of the monarchy arguably mattered. But moving forward, some say, the monarchy will no longer add value either to Britain or to the world, and it will continue to lose relevance until eventually, it’s abolished and the country becomes a full republic.

The Monarchy Will Continue to Be Relevant…

There’s evidence, however, that the monarchy has life left in it. Even before the outpouring of support prompted by the Queen’s death, surveys long indicated that more than 60% of British citizens strongly favor the institution. Though support has fallen a bit in recent years, data indicates it’s remained fairly steady: It’s true that younger people today are less likely to report strong support, but younger generations have always been less likely to do so. In other words, as people age, they’ve historically grown fonder of the monarchy, and overall support has remained relatively stable, despite occasional dips in response to specific circumstances (like the death of King Charles’s first wife, Diana, Princess of Wales).

Further, some observers note that regardless of the monarchy’s popularity at any given moment, the future of the monarchy may be secure for an entirely different reason:

…Because It Serves an Important Purpose

People outside Britain sometimes ask what is the purpose of a purely ceremonial figurehead—but the purely ceremonial aspect might, in fact, be its strongest feature because it separates patriotism from politics.

The monarch is the head of state: Their duties include participating in ceremonies, opening sessions of Parliament, appointing the Prime Minister, and meeting with foreign leaders. As such, they represent the character of the country: its culture.

This role is distinct from the head of government—the person who writes the laws. This distinction allows citizens to feel united under a love of country (their monarch) even while they disagree on its laws and policies.

In most representative democracies, the head of state and the head of government are the same person. In these systems, such as the United States, people often conflate politics with patriotism, leading members of one party to accuse members of another of rooting for the downfall of their country if they disagree on policies.

The monarchy offers a bulwark against this sort of hyperbole; George Orwell described it as an “escape-valve for dangerous emotions” and others note that it provides a sense of continuity that transcends individual administrations. Pro-monarchy advocates maintain, therefore, that the primary benefit of the monarchy is that it unifies the country under a common cause, and thus even if it suffers occasional dips in popularity, it contributes something of value to the country.

The Changing of Hands

There’s debate as to whether current support for the monarchy reflects positive feelings toward the institution in general or toward Queen Elizabeth II in particular, and whether King Charles III will be able to engender the same level of popularity his mother did.

This may depend on how King Charles approaches his role: The Queen’s steadfast refusal to enter into politics or to opine on controversial topics allowed her to present a stable, reassuring front to the public that earned her much affection. Further, her reputation as a representative of old-fashioned values like self-sacrifice, duty, and modesty diverted focus from some of the more problematic aspects of the monarchy, like its history of violence, exploitation, and theft.

Many palace-watchers suspect that King Charles III won’t ever project the gravitas Elizabeth built up over the course of seven decades. He comes across as more aristocratic and petty—a video of him throwing a small tantrum over a broken pen went viral shortly after he assumed the crown—and many British haven’t forgiven him for his treatment of the ever-popular Diana, Princess of Wales. They question, therefore, if he’ll be able to provide the steadying sobriety needed to offset the tumultuous side of British government—and if he can’t, does that render his role pointless?

Some, though, point out that his reign will not be nearly as long as his mother’s, and that his true role may actually be as a placeholder for the younger, more popular generation coming up behind him: William, Catherine, and their son, George. If that’s the case, then it’s plausible that the monarchy will someday again become more popular, and in the long run, will likely survive in some form or another—if not as the head of an extended collection of nations, then at least as an enduring symbol of regional Britishness.

Want to fast-track your learning? With Shortform, you’ll gain insights you won't find anywhere else .

Here's what you’ll get when you sign up for Shortform :

- Complicated ideas explained in simple and concise ways

- Smart analysis that connects what you’re reading to other key concepts

- Writing with zero fluff because we know how important your time is