This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Steve Jobs" by Walter Isaacson. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What was Steve Jobs’s leadership style like? Why did he only see things as black or white?

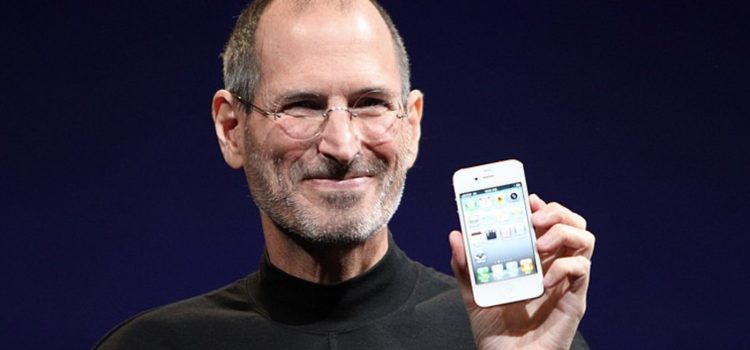

Walter Isaacson’s book Steve Jobs is a raw depiction of the entrepreneur’s life. Isaacson didn’t hold back and wrote how Jobs sometimes had a controversial approach to leadership at Apple.

Continue reading to learn more about Steve Jobs’s leadership style.

A Black-and-White View

Was Steve Jobs’s leadership style harsh? Despite the brilliance of Jobs’s leaps of insight, his belief in the power of his own intuition let him fall into the trap of binary “either/or” thinking. Isaacson argues that this temperament colored not only Jobs’s vision of the future but the way he treated the people around him. In Jobs’s eyes, every person he met was either a genius or an idiot. Every idea was either brilliant or rubbish. Every product was either the best or it was garbage.

(Shortform note: Binary thinking has a certain value in “winner-take-all” scenarios, but it blinds you to situations where solutions require trade-offs. In A New Way to Think, management expert Roger L. Martin argues that truly successful leaders are able to consider opposing ideas at the same time and synthesize new ones with the best qualities of both.)

Jobs was vocal about his opinions and would use them to build people up or tear them down, sometimes on the very same day. This type of behavior was particularly manipulative—Jobs would berate a hapless colleague, then later put them on a pedestal. This made people eager to please him and terrified of failing to do so. (Shortform note: The idea of tearing someone down in order to build them up may have some, albeit controversial, value in strengthening a person’s self-esteem. However, when it takes place in interpersonal relationships, it’s more often a sign of narcissistic manipulation.)

Those who worked with Jobs the longest learned to reinterpret his extremist opinions. For example, if Jobs said an idea was stupid, they decided that he was really saying, “Explain your idea. Why is it good?” In one incident that Isaacson recounts, Jobs verbally accosted an engineer on the Mac team about a design he wasn’t happy about. The engineer then had to go on at length about why he’d developed the design the way he had. Because of the way he had to spell out his thoughts, the engineer then discovered an even better solution than the one he’d originally shown Jobs.

However productive, Jobs’s angry tirades were needlessly hurtful to staff and morale. His “tantrums,” as Isaacson calls them, could extend to anyone he might interact with—waiters, hotel staff, and even business associates. His colleagues found that the only way to deal with him at times was to push back against him just as hard as he did.

A Tyrannical Taskmaster

Jobs was driven by a singularity of vision when it came to anything he had a hand in designing. Once he knew what it was he wanted, whether it was a photo for an ad campaign, the layout for an Apple Store, or a particular shade of blue for a computer, he wouldn’t stop until he’d got it just right. (Shortform note: A demanding, no-holds-barred leadership style can certainly produce positive results, such as when Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla drove his company to produce its Covid vaccine. However, it can also negatively impact productivity and morale. In The 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership, John Maxwell identifies serving and empowering the people you work with as vital characteristics of good leaders—traits where demanding CEOs like Jobs fall short.)

The intensity of Jobs’s creative vision, coupled with his lifelong desire for perfection, caused him to lead others with a very heavy hand, inadvertently creating many of the pitfalls that plagued his first tenure at Apple and at NeXT. Isaacson says that Jobs’s laser focus on minute details would often result in delays, cost increases, total redesigns, and overworked employees. Taken to extremes, his perfectionism led to ridiculous demands, such as that the NeXT computer be a perfect cube, regardless of its engineering needs.

Isaacson points out that Jobs’s need for control is what defined Apple’s stance in the debate between open and closed computer systems, which led to Microsoft’s greater market share. This same conflict resurfaced in the 2000s when Google released its open Android system to compete against the iPhone’s closed OS.

While Jobs’s vision often led him to act as a dictator, his colleagues learned that they could challenge him if they had better ideas than his. (In fact, the team that designed the Macintosh instituted an annual award for the employee who pushed back against Jobs the best.) Many of the people who worked with Jobs grew into tougher, more visionary people themselves.

Despite Jobs’s often tyrannical behavior, he had a skill for fostering group collaboration. Many companies in the corporate world are fractured, split into divisions that compete against each other. Jobs would not let that happen, either at Pixar or at Apple. When Jobs designed a new building for Pixar, Isaacson says that he deliberately set it up so that teams working on different film projects weren’t segregated; they’d be forced to interact, even if by accident. At Apple, instead of having engineering, production, and marketing work on their facets of any project separate from each other, Jobs would insist that all divisions work in tandem, allowing for a cross-pollination of ideas.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Walter Isaacson's "Steve Jobs" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Steve Jobs summary:

- A no-fluff look into the life of Steve Jobs

- How Jobs changed the technology landscape

- What it was like to work with and for Steve Jobs