This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "The Tipping Point" by Malcolm Gladwell. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What was the purpose of the Stanford Prison Experiment? What were its findings? What does it say about our tendency to overestimate the importance of personality traits over social pressures?

We’ll cover the purpose and findings of the Stanford Prison Experiment and discuss its implications.

Purpose of the Stanford Prison Experiment

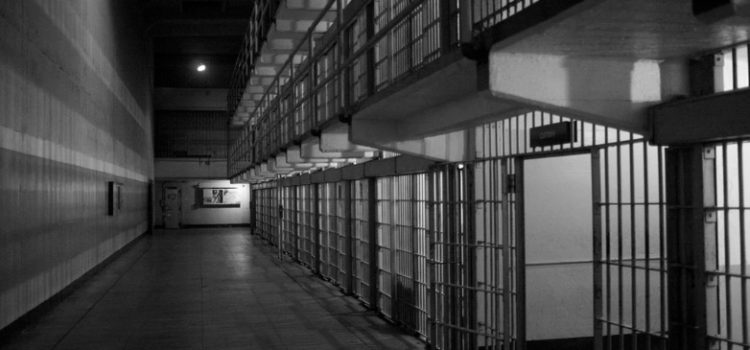

An example of social context impacting our behavior is the Stanford Prison Experiment, in which participants were randomly assigned the roles of either prisoners or prison guards.

The participants assumed their roles to such an extreme that they acted cruelly and completely out of character; the prison guards abused the prisoners, waking them up in the middle of the night to do push-ups and random tasks, spraying them with fire extinguishers, making them march handcuffed and with paper bags over their heads, and even throwing one prisoner into solitary confinement. The behavior was so alarming that the two-week experiment was ultimately called off after six days.

Findings of the Stanford Prison Experiment

After the experiment, participants recognized that they had acted dramatically differently than they ever would have believed possible. The context of the experiment, with their temporary roles as prisoners or guards, was enough to overpower their natural disposition and totally alter their behavior. The fact that voluntary participants in an experiment could be so overtaken by their context suggests that it is entirely possible to create (much less drastic) behavioral changes in a targeted audience in order to tip an epidemic.

This was the purpose of the Stanford Prison Experiment: According to the Power of Context, people are so sensitive to conditions and changes in our environment that context can determine whether or not an epidemic tips.

Subtle, seemingly insignificant changes in our immediate environments can make us more likely to change our behavior; when done on a broad enough scale, this can ignite an epidemic. These changes may be in our physical environment or social context. Demonstrating this was the purpose of the Stanford Prison Experiment.

The Power of Social Context

We tend to think of ourselves as products of nature and nurture, meaning the greatest influences on who we are and how we behave are our genetics and our upbringings. However, context is so powerful that certain situations can eclipse our natural dispositions. This was demonstrated by the Stanford Prison Experiment findings.

The Fundamental Attribution Error is a psychological term for humans’ tendency to overestimate the importance of fundamental personality traits in explaining people’s behaviors, and underestimate the role of context. In other words, when we see someone behave a certain way, we’re more likely to assume it’s a fundamental personality trait, rather than the influence of temporary context.

For example, two comparably skilled basketball players are shooting baskets, but one is in a well-lit gym and one is in a dimly lit gym. The player in the well-lit gym obviously makes more baskets. But when spectators are asked to judge which of the two is more skilled, they choose the player in the well-lit gym, disregarding the conditions (better lighting) that greatly contributed to his success. This is a less severe example than the Stanford Prison Experiment findings, but the study served a similar purpose.

We make this error because human brains evolved in a way that makes us very good at processing certain kinds of information — and bad at processing others. The Fundamental Attribution Error makes the world simpler and easier to understand than considering all the variables of context, but it creates a blind spot in our understanding of all kinds of actions and events, from cheating to committing crime.

Although it’s humbling to admit that we are so inept at judging the causes of most situations, the Power of Context is actually promising: Problematic behavior is not the inevitable actions of inherently bad people, but instead is the result of context and circumstances that can be changed and adjusted for a better outcome. Your character is not a fixed set of inherent traits — as the Fundamental Attribution Error would have us believe — but a collection of habits and tendencies that are subject to change under different conditions and context; many of us appear to have consistent character traits only because we are good at controlling our environments. Showing this was the purpose of the Stanford Prison Experiment.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "The Tipping Point" at Shortform . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full Tipping Point summary :

- What makes some movements tip into social epidemics

- The 3 key types of people you need on your side

- How to cause tipping points in business and life