This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Skin in the Game" by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What is Nassim Taleb’s book Skin in the Game about? What is the central premise of Taleb’s “skin in the game” philosophy?

Skin in the Game is the fifth book in Taleb’s Incerto series. The main idea of the Incerto is that the world is fundamentally unpredictable, and Skin in the Game is about the ethics of living in that uncertain world.

Below is a brief overview of the key points.

Having Your Skin in the Game Is Having Something to Lose

According to Taleb, our first impressions of how the world works are often not just wrong, but dangerously contradictory to reality. Institutions that ignore the need for skin in the game are doomed to fail, and they’ll likely cause widespread harm along the way.

In his book Skin in the Game, Taleb explains why:

- Explain why skin in the game is so beneficial

- Explore the ways in which skin in the game effectively runs the world

- Critique institutions and industries ruined by the absence of skin in the game

- Discover what skin in the game can tell us about the meaning of life

| Origins of “Skin in the Game” Taleb originally formalized his view of “skin in the game” in his 2012 book Antifragile. The main idea of Antifragile is that a certain amount of stress and chaos makes some “antifragile” things stronger, like how breaking down muscle during a workout triggers growth. “Skin in the Game” was the name of a chapter near the end of that book, in which Taleb applies the idea of antifragility to ethics. People who don’t have skin in the game are essentially stealing antifragility, which is unethical. For example, if a popular finance pundit offered bad investment advice that drove up sales of his book, he would become more antifragile, profiting from uncertainty. It doesn’t matter if the advice works or not—he comes out ahead either way. However, the investors taking the bad advice would become more fragile, as they’re at greater risk of losing money. |

Why Put Skin in the Game?

Taleb believes that an ideal system—whether it’s a country, a company, or even a religion—is made up of as many people with as much skin in the game as possible. Why?

First off, skin in the game allows us to learn from our mistakes. Taleb is adamant that knowledge gained through direct experience is far more reliable than knowledge sussed out through abstract reasoning. Individuals improve by learning from painful failure. An actress could read a million books on acting theory, but if she doesn’t go out and risk falling flat in auditions or on stage, she’ll never improve.

Likewise, systems improve by eliminating components that don’t work. If every failing business were given bailouts in order to continue running—if they carried no risk and didn’t have skin in the game—we would be surrounded by suboptimal businesses.

Secondly, skin in the game inspires better work. People are more engaged when their skin is in the game. They’re less likely to get bored, more likely to put in effort, they’ll make better decisions, and they generally feel more fulfilled. A teenager would be much more engaged during her driver’s license test than during the drive to a friend’s house. This is because she has something to lose if she fails her driving test—skin in the game. Ideally, all jobs would incorporate an element of skin in the game, creating something to lose by tying rewards to results.

Lastly, people behave more ethically with skin in the game. People are less likely to give in to temptation if they know they’ll be punished if they get caught. Telling your four-year-old that he’ll get a time-out if he hits his brother is putting his skin in the game.

An organization whose members lack skin in the game will be unable to learn from its mistakes, will care less about accomplishing its goals, and will foster corruption. This is because without skin in the game, individual agents are separated from the consequences of their actions.

Employees Put Skin in Their Employers’ Game

Taleb argues that employment, the source of most of the wealth in our modern society, is only possible through a very specific kind of skin in the game.

Companies that produce massive amounts of wealth require reliable employees, as any failure in the assembly line comes at enormous cost. Employers ensure reliability by giving employees something valuable that they don’t want to lose—a secure income, benefits and perks, and a sense of personal identity. This is the skin employees have in the game.

Using this example, Taleb establishes the broader principle that freedom comes from bearing one’s own risks. By binding themselves to the company’s “Game,” employees sacrifice their personal freedom, and they can only get it back by embracing personal risk—quitting and finding a new way to provide for themselves.

Skin in the Game Produces the Fairest Economy

Taleb argues that wealth earned through skin in the game contributes to society in a healthy way. What most people resent is not economic inequality, but economic unfairness—that is, earning money without producing value, giving without taking, having no skin in the game.

Taleb states that this economic unfairness can be measured with a metric he calls “dynamic inequality,” or two-way income mobility—how easy it is to earn more wealth or lose the wealth you have. A perfectly Dynamically Equal society would be one in which no individual spends more time in any one income bracket than anyone else. Taleb asserts that, when analyzed dynamically, the United States is far more economically fair than most assume—for instance, more than half of all Americans will eventually spend at least a year in the top 10% of income earners.

Taleb argues that the free market already rewards those who take risks to create value, so the way to reduce inequality is to force top earners to risk their wealth in order to keep it. He asserts that dynamic inequality is worst in places with a large centralized government such as France, where officials actively protect the salaried executives of large corporations without skin in the game.

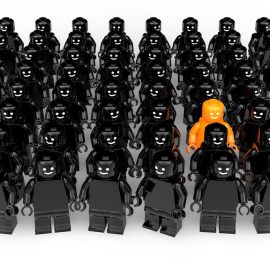

Small Groups With Skin in the Game Shape the World

Another way skin in the game makes the world better is by empowering small groups. Taleb argues that the state of the world is largely the result of minorities passionately fighting for what they want rather than a majority’s consensus. These small groups forcibly put as much skin in the game as possible, making more sacrifices than anyone else is willing to make in order to get what they want.

For example, Taleb credits the original spread of Islam to specific “stubborn” religious rules—anyone who married a Muslim had to permanently convert to Islam, along with any future children. Across many generations, these uncompromising rules overpowered many religions with more lax requirements.

You can be part of a “passionate few” yourself! History shows that no matter what change you want to make in the world, if you’re persistent enough, people less committed than you will bend to your passion.

All Virtue Requires Skin in the Game

Finally, Taleb argues that any action that makes the world better by definition involves some skin in the game. He defines courage as the tendency to put skin in the game—in other words, the willingness to bear risk and make sacrifices. In Taleb’s eyes, this is the highest virtue because anything done to benefit others requires some amount of risk that you must be prepared to bear.

For this reason, the only way for seemingly virtuous action to lack skin in the game is if it also benefits the one doing the virtuous action. The return benefit takes your skin out of the game by offering you a reward independent of the well-being of the person you’re trying to help. If a man only volunteers at soup kitchens as a means of picking up women, it obviously makes his work less virtuous.

Taleb argues that people who make a living in “altruistic careers” outside of the free market—whose income comes from donations or taxes—don’t have skin in the game. As a result, they’re far more likely to inadvertently cause harm than entrepreneurs who are paid directly by those they’re serving.

Why Systems Without Skin in the Game Fail

Systems that involve skin in the game naturally improve over time. When people with skin in the game make efforts to minimize risk and loss, they eliminate whatever doesn’t work, leaving behind only what is useful and effective. Salespeople eliminate strategies that fail, managers fire salespeople that don’t sell, and the competitive market eliminates firms that don’t turn a profit. Given enough time and skin in the game, everything effective will survive and everything ineffective will die out. Taleb asserts that this process is the only inerrant judge of quality.

Taleb wrote Skin in the Game in explicit opposition to an ideology he calls “Intellectualism.” Intellectualism states that rational humans have the capacity to replace skin in the game as judges and reliably distinguish good from bad. Consequently, intellectualists believe that systems should be designed by a select few instead of being allowed to evolve over time. In Taleb’s view, Intellectualism overestimates the reliability of human intellect and underestimates the world’s complexity and unpredictability.

Taleb repeatedly uses the book Nudge as an example of Intellectualism. Economist Richard Thaler argues that those offering choices—for example, a company offering multiple retirement plans—should “nudge” people to make better, more “rational” decisions, without limiting their options. In Taleb’s eyes, any “nudge” that directs behavior is an unwarranted intervention in a complex system that will likely cause harmful side effects.

Intellectualism fails because human judges are fallible. It’s far more likely that humans will make bad decisions than good ones. If fallible human judges within a system lack skin in the game and can’t be eliminated for their mistakes, flaws will pile up, undetected, until the system crumbles. Next, we’re going to look at specific industries and institutions where this is happening.

Science and Academia Lack Skin in the Game

Taleb argues that the world suffers from a lack of skin in the game in science and academia. Ideally, scientific fields would be dominated by skeptical experimenters who are rewarded for devising a more accurate understanding of how the world works by disproving the theories that come before them. Unfortunately, modern science has strayed from this ideal because researchers lack skin in the game.

Instead of judging research by how well it stands up to skeptical experimentation, peer review has become the ultimate judge of quality science. Since peer approval is a reciprocal process, as long as a group of academics reaches consensus, the validity of their ideas doesn’t matter. They can create a feedback loop of approving each others’ research, earning themselves funding and tenure with no penalty for being wrong. Additionally, Taleb argues that misinterpreted data often leads to invalid conclusions—academics don’t verify their knowledge in the real world nearly enough.

Taleb argues that these flaws yield inaccurate conclusions and misguided theories that can cause major harm if applied at a large scale in the real world.

Taleb asserts that the only way to ensure effective scholarship is to stop paying scientists to conduct research. Instead, we should require working professionals to conduct research on their own time. This puts the skin of researchers back in the game—they have to sacrifice time, money, and effort in the name of science if they want the rewards of discovering something valuable.

| Why Do Researchers Lack Skin in the Game? Taleb argues under the assumption that academia lacks skin in the game, but he doesn’t explain how or why this came to be. Only a small fraction of scientific research ends up providing practical benefits to society, and it’s difficult to predict how valuable any given line of research will be until after these discoveries are made. If valuable discoveries were predictable, they would have already been discovered. For example, Alexander Fleming, the scientist who discovered penicillin, initially failed to recognize the practical value of his discovery. It was more than ten years before it was used as a revolutionary antiseptic. Since it’s difficult to predict the value of scientific exploration, the majority of researchers get paid salaries for research that in the end generates little value. Researchers don’t bear the financial risks of their research, and this imbalance between risk and reward is a lack of skin in the game. Thus, fallible human judges are the ones evaluating research instead of the inerrant judge of time, which, as we’ve discussed, causes problems. |

Centralized Government Lacks Skin in the Game

Centralized government is another system that harms the world due to a lack of skin in the game, according to Taleb. In his eyes, centralized government invariably results in mismanagement and corruption at a large scale. Instead, Taleb is a strong advocate of the decentralization of power, as mentioned earlier.

Taleb identifies one common misconception that he believes contributes to many of the world’s biggest problems: Those who support centralization mistakenly assume that the logic and ethics they use to make decisions on a small scale will have the same effects at a large scale. In reality, when those in power make decisions at a large enough scale, the intellect and morals they use on the individual level fail to effectively do good.

(Shortform example: The European Union’s “Common Agricultural Policy” launched in 1962 instituted extreme farming subsidies across the continent. Maintaining a stable food supply for the collective is a rational, moral goal. However, in practice, the policy has failed to do good. It has increased the price of food (which hurts those in poverty the most) and funneled millions of dollars to corrupt government leaders like the Prime Minister of the Czech Republic.)

Human intellect is fundamentally limited. Large governments manage such large, complex systems that their intervention and attempts at restructuring are far more likely to be harmful than beneficial. Ensuring that decision-makers have as much skin in the game as possible protects us from leaders with too much faith in their own intellect and morals.

| Scaling Is the Heart of Taleb’s Politics The cornerstone of Taleb’s political perspective is that groups of different sizes behave in extremely different ways—as stated in Skin in the Game, it’s possible to be “at the Fed level, libertarian; at the state level, Republican; at the local level, Democrat; and at the family and friends level, a socialist.” Since the rules change as groups grow bigger, you need to adopt different philosophies for groups of different sizes.In the Scala Politica, Taleb’s book-length political manifesto published as an academic paper, Taleb argues that borderless globalism is impossible—people naturally care about their own families and sometimes their own nations, but they wouldn’t find the same sense of meaning if they could only relate to humanity as a whole. Additionally, there is no one way of life that will satisfy everyone on earth. This requires a system that allows “tribes” of different sizes (families, nations, religious communities) to coexist and set their own rules. |

Journalists Lack Skin in the Game

Another area in which the absence of skin in the game makes the world worse is the news industry. Taleb argues that because journalists lack skin in the game, news institutions become dominated by a single point of view. They often misrepresent the facts in pursuit of their own interests because there is no penalty for doing so. Errors in the news go undetected by most, and they typically aren’t extreme enough to provoke a libel suit.

Ideally, news flows in two directions—everyone is equally able to send and receive news. This way, those who spread news have skin in the game, as unreliable reporting costs them their reputation. This arrangement was commonplace in the era of village gossip but disappeared when newspapers and radio took over. Now, Taleb asserts that social media has reborn two-way news and is destroying unreliable news sources in the process.

| Internet News Takes Skin Out of the Game In Trust Me, I’m Lying, the Daily Stoic’s Ryan Holiday recounts his experience as a marketing director exploiting flaws in the Internet-based news media. Holiday explains that advertising-driven blogs—which comprise the majority of online news sources—earn income based solely on pageviews, and as a result, they put greater emphasis on sensational, attention-grabbing news and less on balanced perspective and reliable fact-checking. As Taleb points out, journalists’ skin is not in the public’s game. |

War Is Propelled by Institutions That Lack Skin in the Game

Lastly, leaders and institutions that perpetuate war without skin in the game cause the world great harm. Taleb argues that populations with skin in the game tend to fight shorter, relatively non-destructive wars, and that all the bloodiest conflicts in history were driven by third parties.

War puts mass skin in the game, not only for the people doing the fighting, but everyone who bears the risks of war—all civilians who suffer domestic turmoil and a stressed economy. The mutual drain of resources required by war puts constant pressure for peace on both sides. But if the ones ordering the war aren’t personally suffering its dire consequences, it’s more likely to continue.

For Taleb, this is another reason why decentralized states are better than a large unified nation—centralized governments are more likely to participate in deadlier wars because the decision-makers are farther away from the people making the sacrifices.

Additionally, foreign efforts to implement peace by powers without skin in the game cause more problems than they solve. Even if a war is settled on paper among dignitaries, if the people themselves aren’t the ones to reconcile, the underlying conflict won’t go away.

| The War of Peace Taleb has engaged in a lengthy feud with psychologist Steven Pinker on the topic of whether or not violence has declined over the course of history. Taleb’s chapter on war is partially a response to Pinker’s 2011 book The Better Angels of Our Nature, in which he argues that the world is safer and more peaceful than ever before. Pinker credits this in part to powerful democratic human institutions such as the United Nations that Taleb disdains. Taleb argues that the seventy or so years of overwhelming peace we’ve had since World War II could simply be a statistically predictable gap between massive wars, and that centralized institutions intended to create peace often cause more conflict than they resolve. |

Philosophical Implications of Skin in the Game

We’ll conclude by discussing the philosophical implications of skin in the game. It’s a fundamental human truth that skin in the game is at the core of everything valuable or meaningful. How much we value something can be measured by how much we’re willing to risk for it.

By examining what humans universally are willing to sacrifice for, Taleb concludes that everything we do is a means toward one end: our survival and the survival of the human race. We build houses to protect us from nature, we build cities to help us collaboratively fulfill our survival needs, and we create technology to help us live longer and easier lives.

With this in mind, Taleb argues that instead of defining “rational” beliefs as those that align with our understanding of the way the world works, we should see any belief that enables survival as rational. It’s impossible to judge the rationality of beliefs using logic and abstraction. The universe is too incomprehensibly complex—there will always be unknown factors that could lead us to faulty conclusions.

Instead, Taleb judges the “rationality” of beliefs by how long the beliefs (and the populations who held them) have survived. For example, the skin in the game-based principle that criminals should be punished for their crimes has lasted for thousands of years because it helps societies survive.

This leads Taleb to conclude that lasting traditional religions are all rational belief systems because they aid humanity’s survival. The validity of their metaphysical claims doesn’t matter—if they encourage action that leads to survival, they should be respected as rational beliefs. Moral commandments that motivate believers to put skin in the game are one example of this kind of “rational” belief.

| Critique of Taleb’s Rationality This definition of rationality is a recurring point of contention among Skin in the Game’s critics. If we were to totally refrain from abstract judgment of beliefs and instead wait for them to play out over years to see if they survive, truly irrational beliefs could cause massive amounts of suffering—as an extreme example, if the Allied Forces had allowed Nazi Germany’s ideas to play out, they could have destroyed the world. It’s necessary to label some beliefs as irrational.It’s impractical to assume that all new beliefs are inferior to traditional ones. Taleb’s assertion that “everything that survives survives for a reason” doesn’t necessarily prove his more extreme point that every belief that has survived has aided that survival. Sometimes, beliefs survive despite hurting our chances of survival—people believed in medicinal bloodletting for thousands of years. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Nassim Nicholas Taleb's "Skin in the Game" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Skin in the Game summary :

- Why having a vested interest is the single most important contributor to human progress

- How some institutions and industries were completely ruined by not being invested

- Why it's unethical for you to not have skin in the game