This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "A Theory of Justice" by John Rawls. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What is John Rawls’s definition of justice? How does Rawls’s conceptualization of justice differ from other theorists’?

According to John Rawls, justice is a generally held idea of the most moral way of organizing society. Thus, Rawls doesn’t focus on justice on an individual level, which separates him from many other theorists of justice, who view social justice as an extension of individual justice.

Keep reading to learn about Rawls’s concept of justice.

Rawls’s Definition of Justice

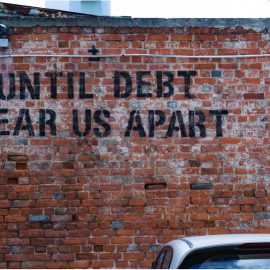

John Rawls defines justice as the dominant ideology or goal underlying the rules of society—in other words, why people create and follow a society’s rules. Rawls says there’s no universal sense of justice that all societies agree on; different societies have different theories of what’s just and unjust. Members of each society try to make specific political and economic rules that are just—according to their own theory of justice.

These rules then determine how that society distributes “primary benefits”: things that help people achieve their goals in life no matter what they might be. Rawls says the main primary benefits are rights, liberties, opportunities, wealth or income, and a sense of self-worth (not being treated as inferior by society).

(Shortform note: One consequence of Rawls’s definition of justice is that he doesn’t concern himself with justice on an individual level—in a specific court case or moral dilemma, for example. For example, 18th-century Prussian philosopher Immanuel Kant uses the principles of the categorical imperative (a pair of universal moral laws) not only to judge what’s just for an individual, but also what’s just for a nation—both on a domestic and international scale.)

Here’s an example of how a principle of justice informs a rule, which in turn informs the distribution of a primary benefit:

| Capitalism Under Justice as Fairness From its very beginnings, liberalism has been closely tied to capitalism, or private ownership of industries for individual profit. Early liberals like John Locke viewed the right to own private property as a fundamental human right, arguing that a just government could not and should not interfere with it. In addition, liberals like 18th-century Scottish philosopher Adam Smith argued that people acted as rational, self-interested individuals in a capitalist free market, an idea that liberals also apply to the political realm. Rawls himself uses the ideal of the rational, self-interested individual in his construction of the original position as seen above. Rawls justifies his own version of capitalism—he claims that inequalities of wealth (private ownership) allow a state to function more efficiently than in a state of complete equality. However, Rawls argues for a far more limited conception of capitalism, one regulated by the state to try and ensure fairness and general well-being. This is a middle ground between right-wing classic liberalism and its critics on the left: Classic liberals like Smith believe government interference in the market disrupts the generation of wealth in society and therefore disrupts general well-being, while leftist critics of liberalism like Karl Marx argue that capitalism is built on exploitation and therefore cannot work for the common good in the way Rawls wants it to. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of John Rawls's "A Theory of Justice" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full A Theory of Justice summary:

- John Rawls's 1971 theory of justice as fairness

- A breakdown of Rawls's Original Position theory and framework

- The three duties every citizen has in a just society