This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "TED Talks" by Chris Anderson. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What makes a good public speaking voice? Is it better to speak in a flat or oscillating voice? Where should you put emphasis as you speak?

The best speech in the world will fall flat if the speaker doesn’t appear and sound genuine and passionate. According to Chris Anderson, the author of TED Talks, there are three things you can do with your voice and body to be as enigmatic as possible when speaking.

Here’s how to bring your best to stage using voice and movement.

Technique #1: Speak With Inflection

When it comes to public speaking, voice and inflection are extremely important. Nobody wants to listen to a robot. Anderson argues that a speech without emotion and inflection will accomplish the same (if not less) than if you emailed your words to the audience. To inspire your listeners, use your voice to show them which parts are important. When should they be angry? When should they feel sympathy? Guide them with your voice. If, while rehearsing, you struggle with where to add inflection, Anderson offers a strategy:

- Underline the most important sentences in your speech. When you’re practicing your speech and see this, put a stronger emphasis into your voice.

- Double underline the most important words and put even more emphasis there.

- Draw a wavy line under the less important sentences. These ones you can breeze through casually while speaking.

- Put a blob of ink before the biggest moment in your speech and use it as an indicator to add a dramatic pause.

Anderson suggests that you record yourself using these strategies, listen to how you sound, and make adjustments accordingly.

| The Power of Voice in Communicating Emotions Anderson says that speaking is more powerful than written communication as long as there is emotion and emphasis in your voice. One study supports this notion by showing that when it comes to communicating emotions, sound carries as much weight as words. A 2019 study conducted at UC Berkeley determined that humans can identify at least 24 emotions via sound without any words being used. The researchers used nonverbal exclamations that they titled “vocal bursts” and found that listeners could easily distinguish emotions between similar sounds—for example, a sigh of relief and a sigh of disappointment, or a surprised gasp and a scared gasp. They created an interactive sound map to display their findings. This study shows how much power our literal voices hold when we speak. If the sounds you make support your words, the audience will trust you. However, if they don’t align, your audience will be confused at best and distrustful at worst. |

Avoid Orating

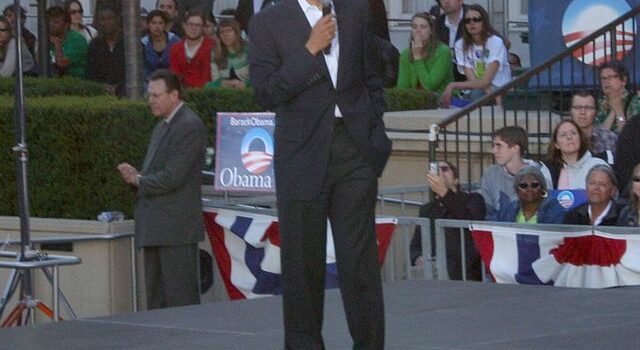

While emotion and emphasis are important in a speech, Anderson strongly warns against oration. To “orate” is to speak in a grandiose manner—slowly, loudly, and with many dramatic pauses. Anderson says many people believe this type of speaking is authoritative and inspirational, but there are few occasions when it’s appropriate.

Some of the most famous speeches in history were orations. For example, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream,” and John F. Kennedy’s “Why Go to the Moon?” speeches were both recited in this manner. Anderson explains that some situations are primed for orations—church sermons or social justice rallies, for example. He adds, however, that most topics don’t warrant this type of speaking and will come across as arrogant or gimmicky. This is especially true if the audience doesn’t know who you are.

Anderson recommends you opt instead for a more conversational tone. It’s relatable to the audience and forges a genuine connection. Casual speaking also translates better on video, so keep this in mind if your speech is going to be recorded.

| Too Much Drama Can Weaken Your Message Anderson says that orating when it’s not appropriate can negatively impact the way your audience sees you. Besides the risk of coming across as arrogant or gimmicky, another reason to avoid orating is that it can cause the audience to miss or forget your message entirely. When done in excess, your displays of emotion can overshadow the content of your speech. How much emotion is too much? If your passion for the subject inspires your audience, then you’ve used the correct amount; if your passion distracts the audience from your message or topic, then you’ve used too much. If the audience is feeling uncomfortable or embarrassed for you (for example, if you burst into tears on stage), then they’ll be distracted from your message. If your gestures are so over the top that the audience laughs when you’re trying to solicit a serious response, this is another sign that your behavior is distracting. An example of distracting behavior is Tom Cruise’s infamous couch jumping on The Oprah Winfrey Show. Afterward, all anybody talked about was his behavior—whatever he actually said during that interview was quickly forgotten. Bottom line: When the audience leaves, you want them talking about the content of your speech, not about you and your performance. |

Technique #2: Vary Your Speed

Anderson disagrees with the conventional wisdom to slow down when you’re giving a speech. Between speaking too quickly and speaking too slowly, he says the latter is more dangerous because you risk boring your audience and losing their attention. Speaking too slowly can also insult their intelligence, he adds. So rather than trying to slow down, focus on changing up the speed of your speech. The fluctuation will help keep your audience’s attention and will also help them comprehend the content.

If you’re not sure which parts of your speech should be fast or slow, Anderson offers some general rules:

- When you’re telling an anecdote, speak more quickly because the information is easy to take in and process.

- When you’re explaining a concept, slow down so the audience has time to digest and comprehend the information.

- Add a few pauses to highlight important points or to allow the audience time for laughter.

| Analyze Your Spoken Words Per Minute Anderson says that speaking too quickly is better than speaking too slowly, but it is possible to speak so quickly that you lose your audience. Extremely fast speech often sacrifices enunciation, so words can slur in an incomprehensible jumble. In addition, if listeners have to concentrate to keep up, they are likely to miss information and be irritated at the same time. How fast is too fast? If you practice your speech on an audience or record yourself and listen, you should get an idea whether or not you need to slow down. If you prefer concrete data, you can calculate your spoken words per minute (WPM). Elizabeth Gilbert, who is known for speaking very quickly, spoke 187 WPM during her TED talk. Al Gore (known for being a slow talker) spoke 135 WPM during his TED talk. To calculate yours, record a few minutes of your speech in a “talk to text” app, run a word count, and then divide that number by how many minutes you spoke. |

Technique #3: Move (Or Don’t) in a Natural Way

Anderson acknowledges that some people feel more comfortable moving while speaking, and others feel less so. For this reason, he doesn’t prescribe one or the other, but he does give some tips to try and pitfalls to avoid for both.

If you prefer to walk, Anderson recommends you do so in a relaxed and natural way. When you make an important point, it’s a powerful method to stop walking, face the audience, and pause for a moment before resuming. This variety of walking and stopping can be an effective way to use your body. (Shortform note: Experts warn that too much walking can be distracting, but they encourage crossing the stage during the lighter moments of your speech and transitions between segments.)

If you prefer to stand, Anderson recommends keeping your weight evenly distributed between both feet. Avoid leaning to one side, continually shifting your weight, or rocking forward and backward. Those movements can be very distracting. Keep good posture in your spine and shoulders and use your hands to gesture to the audience from time to time. (Shortform note: This isn’t to say that you should stand still like a statue. Natural shifting of your weight is okay; rhythmic movement will draw the eye. You can also gesticulate with your upper body to keep from looking and feeling stiff.)

If you prefer to sit (or need to because of a physical constraint) this is okay as well. Anderson emphasizes that there are no hard and fast rules about standing or sitting during a speech. Whichever method of movement (or stillness) that you choose, he stresses that it only be done in a natural way. (Shortform note: With the recent increase in video conferencing, it’s more common than ever to sit while presenting. In this instance, focus on posture (sitting straight with shoulders back) to display confidence, and use hand gestures and facial expressions for emphasis and emotion.)

Anderson suggests you record yourself giving your speech and pay specific attention to how you move your body. Ask your practice audience if anything you did with your body was distracting or off-putting, and make adjustments accordingly.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Chris Anderson's "TED Talks" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full TED Talks summary :

- A nuts-and-bolts guide to public speaking that takes you from the initial idea to your final bow

- TED curator Chris Anderson's public speaking advice on everything from scripting to wardrobe

- A comparison of Anderson's advice to that of other public speaking experts