This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Gulag Archipelago" by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

How did propaganda in the USSR operate? What tactics succeeded in misleading the masses?

From the 1930s on, the Soviet Union had an extremely robust and powerful propaganda system, exerting near-total control over how the government was depicted in the media, literary fiction, and education. This was done primarily through historical revisionism and the use of euphemisms.

Continue reading for insights from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn on Soviet propaganda.

A Powerful Propaganda Machine

Propaganda in the USSR operated through two primary mechanisms. Historical events that threatened to embarrass the government were covered up, while successes were exaggerated. The government also used language to obscure reality.

(Shortform note: While Solzhenitsyn focuses on how propaganda was used to cover up political scandals, the strength of Soviet propaganda can also be seen in how economic developments were covered, such as the reporting on the Five-Year Plans, a series of government programs begun in the 1930s to overhaul the USSR’s struggling economy. While the first two Five-Year Plans were successful in modernizing the country’s agricultural and industrial systems, the propaganda machine glossed over delays and claimed inflated production levels.)

Historical Revisionism

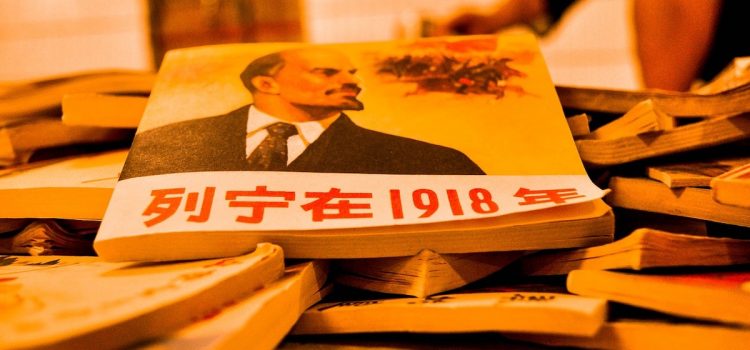

The government continually revised official histories, erasing past events or figures in order to serve current political needs. Solzhenitsyn notes that many Soviet politicians and security officials were imprisoned or disgraced after decades of service, despite having been previously depicted as heroes. The purges of the 1930s, in which Stalin had dozens of his political rivals removed from power and scrubbed from the historical record, were the most famous example of this practice.

(Shortform note: Interestingly, historical revisionism could sometimes act to make society more open and progressive by ending the veneration of authoritarian figures. For example, in 1956, Soviet leader Nikita Khruschev delivered a “secret speech” in which he publicly condemned Stalin’s leadership and the “cult of personality” which had formed around him. This sudden change from universal worship of Stalin to open criticism was a shock to the country, but it opened the door for greater ideological freedom and reform—at least until Khrushchev himself was replaced by Leonid Brezhnev.)

Euphemism

Another aspect of the propaganda system was the widespread use of euphemism or deliberate mislabeling to obscure the realities of mass deaths or human rights abuses. For example, when public news media reported on the widespread use of prison labor, it often called prisoners “volunteers” and downplayed the physically demanding nature of their work.

(Shortform note: Prison labor is widespread in the United States today, and while information about this practice is publicly available, many people remain ignorant of just how many industries rely on prison labor, how poorly prisoners are paid (often cents per day, if at all), and how dangerous their working conditions are. Anti-prison activists argue that prison labor isn’t just economic exploitation, but a direct outgrowth of American slavery—the 13th Amendment, which ostensibly outlawed slavery, includes the exception that forced labor may be used as “punishment for a crime.”)

Mislabeling could also be used to demonize prisoners, thus discouraging people from sympathizing with them. For example, it was common to refer to those arrested for counter-revolutionary or anti-Soviet activity—the crime for which Solzhenitsyn was imprisoned—as “fascists.” Former Red Army soldiers who wound up in the gulag were often depicted as Nazi collaborators, despite the fact that most of them had been arrested for crimes totally unrelated to their military service, and some were even former POWs who had been liberated from concentration camps.

(Shortform note: There were some genuine Nazi collaborators in the gulag. During the war, the Nazis captured and recruited a number of Russian POWs in order to organize them into a makeshift “Russian Liberation Army” led by former Red Army General Andrey Vlasov. After the war ended, those “Vlasov men” who failed to escape to Western Europe were either executed or imprisoned in the gulag. Controversially, Solzhenitsyn defended them by arguing that they were victims of Soviet exploitation who joined the Nazis to survive or to fight against communism, not because they agreed with Nazi ideology.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's "The Gulag Archipelago" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Gulag Archipelago summary:

- A book that was banned for exposing human rights abuses to the world

- A work of historical nonfiction that describes life in Soviet prison labor camps

- How the Soviet government used violence, paranoia, and repression to control their citizens