This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Republic" by Plato. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What kind of a person should lead a society? What makes someone an ideal ruler?

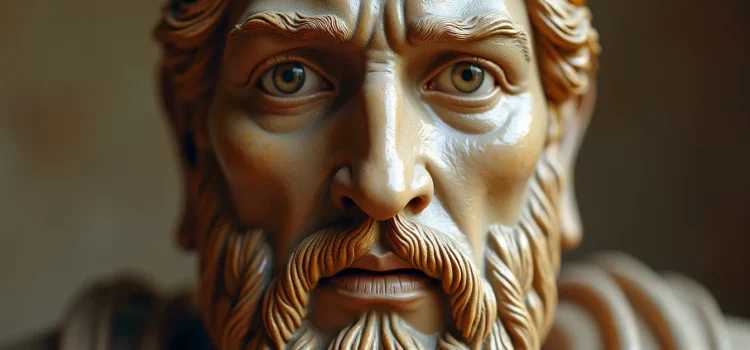

In Plato’s Republic, philosopher-kings are presented as the type of people who are best suited to rule over others. He uses three powerful (and well-known) metaphors to illustrate his point.

Keep reading to discover why wisdom might be the ultimate leadership quality.

The Philosopher-Kings (Plato’s Republic Books V-VII)

In Plato’s Republic, philosopher-kings are described as select protectors who act as the moral leaders and guides of the ideal city. These rulers are emblematic of the city itself and provide a model of a perfectly just life—the kind of life Socrates must prove is preferable in order to win the challenge.

In books V through VII of The Republic, Socrates uses three allegories to show why philosophers are ideal rulers:

- The allegory of the ship shows why philosophers have the character of an ideal ruler.

- The allegory of the divided line explains why an ideal ruler needs philosophical knowledge.

- The allegory of the cave describes how a philosopher uses their knowledge to rule.

(Shortform note: The way Plato describes ruling is closer to moral or spiritual leadership than our modern idea of a high-ranking politician. Philosopher-kings don’t spend all their time on technical management of law and state. Instead, they provide the ideals and goals that those beneath them should strive toward.)

Allegory #1: The Ship

To illustrate the philosophical character and why it’s ideal for ruling, Socrates uses the allegory of a ship and its crew. There are three types of people on the ship: 1) The captain of the ship isn’t a good seaman, but he’s physically strong and charismatic enough to keep everyone else in line. 2) The sailors aren’t much better than him at seafaring, but they desire power—constantly scheming to trick or force the captain to hand over his role. 3) The navigator avoids petty power struggles and instead dedicates himself to learning about weather, astronomy, and other seafaring skills. This makes him an excellent seaman, but nobody listens to him because he can’t help them gain power.

Understanding the Ship

This ship serves as an allegory for Athens. The incompetent captain and power-hungry sailors represent politicians and orators, while the navigator represents the philosopher. Just as the navigator has the necessary seafaring knowledge to guide the ship, the philosopher has the necessary moral knowledge to guide society. And just as the navigator avoids petty power politics and is ignored as a result, philosophers aren’t interested in power and wealth and are therefore ignored.

Socrates argues that just as the navigator is the ideal leader of the ship, the philosopher is the ideal ruler of society. The philosopher’s lack of interest in power and wealth means they’ll be less corrupt, while their focus on knowledge makes them the most competent. Their dedication to knowledge also requires self-control and the courage to keep searching for answers to abstract, universal questions—all ideal qualities in a ruler.

Allegory #2: The Divided Line

To further elaborate on why philosophical knowledge is superior for guiding society, Socrates outlines his theory of human thought and knowledge.

According to Socrates, there’s a hierarchy of human thought—some thoughts or claims are better than others. He argues that the more provable, universal, and unchanging a thought is, the better it is because these criteria determine how certain we can be of its truth. To further illustrate this hierarchy of truth, Socrates compares thoughts to objects in the world. He categorizes them in a line divided into several sections.

Each row of the divided line represents a different category of thought. Let’s explore the hierarchy of these categories in more detail.

Lowest Level: Illusions and Images

Illusions are beliefs not backed by evidence. Socrates says these are therefore the lowest form of knowledge, as very little suggests they’re true. For example, the popular idea that “sunflowers always point toward the sun” is an illusion; it’s commonly repeated and believed even though it has little to no evidence behind it. Socrates compares illusions to our perceptions of images or shadows in the world around us—you see your reflection in a mirror, but there isn’t another real copy of you behind or within it.

Second Level: Opinions and Objects

Opinions are beliefs backed by evidence. They’re therefore superior to illusions but still don’t provide concrete knowledge. For example, there’s plenty of evidence that gravity exists, but we can’t be certain it does or that it always will. Socrates compares opinions to our perceptions of physical objects. We can see and touch a table to see if it’s there, but those perceptions are still founded on assumptions—that we know what a table is, that our faculties are working correctly, and so on.

Third Level: Knowledge and the Forms

Knowledge is provably universally true and unchanging. Socrates explains that we can arrive at knowledge through mathematical and philosophical reasoning. For example, we can use mathematical reasoning to prove that two plus two always equals four and will never stop equalling four. Therefore, we know that two plus two equals four. Similarly, Socrates suggests that philosophical reasoning and debate can provide provable, universal, and unchanging definitions of concepts like justice and beauty.

Socrates explains that knowledge is to thought as forms are to reality. The forms, he explains, are unchanging, universal, perfect versions of objects and concepts that exist in a separate realm. Objects imitate or derive from these forms in the same way that images derive from objects. For example, we understand what a perfect circle is in theory, but all existing circles in the world have flaws, however minuscule, that make them imperfect. The theoretical perfect circle is the form of a circle, and existing circles all derive from that form. All objects—from tables to fish to rocks—derive from their corresponding forms. They can also derive from the forms of concepts—a beautiful table derives from the form of beauty, for example.

Highest Level: The Form of the Good and the Sun

Socrates argues that all forms—and the objects and images that derive from them—derive from the form of the good. Since the forms are perfect ideals, they must be good. You wouldn’t call a perfect circle a bad circle, for example.

Moreover, knowledge—the way we determine what is true and how we grasp reality—comes from an understanding of the forms. Therefore, the form of the good is the ultimate source of all knowledge and truth. Socrates compares the form of the good to the sun: Just as the sun provides the warmth for things to grow and the light for us to perceive them, the form of the good provides the reality for us to study and the truth for us to make sense of it.

Allegory #3: The Cave

After explaining the superiority of philosophical character and philosophical knowledge, Socrates describes how these elements combine to create an ideal ruler. He does so through an allegory of a cave, which describes the education and leadership of the ideal city’s philosopher-king.

Inside the cave, people are restrained so they permanently face the back wall. A fire is lit behind them, and various items are placed in front of it to project shadows on the wall. Because they’ve never seen anything else, the people in the cave believe these shadows are actual real objects. But one day, a man frees himself from his restraints, turns around, sees the items in front of the fire, and realizes the shadows are just images cast by them. Then, as his eyes adjust to the light, he’s able to ascend from the cave, see reflections and objects outside, and then eventually look up to see the sky. There, he’ll finally see that the sun provides the necessary light for all objects and shadows to be visible.

If he returns to the cave, his eyes will struggle to adapt to the darkness, and everyone inside will assume he’s delusional if he tries to explain what he’s seen outside. While he would prefer to spend all his time outside and see the true world, he knows he must return for the good of everyone in the cave—his community. When he does, he’ll understand the shadows far better than anyone else inside because he’s seen the objects that create them. He’ll therefore be far better suited to educating and guiding everyone else.

Understanding the Cave

Combined with an understanding of the divided line, the allegory of the cave represents the role of a philosopher-king in society. In mundane society, people are focused entirely on conventional wisdom and worldly affairs like wealth and petty politics—just as people inside the cave are focused on shadows.

But those with a philosophical character find worldly affairs insufficient to explain the nature of the world around them. In the ideal city, they’re selected from the protectors and educated to become philosophers. This education mirrors the ascent from the cave, going from basic, universal education (illusions and objects) to mathematical reasoning, philosophical reasoning, and the form of the good (the sky and sun). This process lasts several decades, allowing the philosopher-king’s mind to adjust to this new understanding of reality just as the cave man’s eyes adjusted to the light.

Because of their love of knowledge, the philosopher-kings will want to keep studying the forms indefinitely. However, they’ll recognize that they must rule because they’re best suited to the task—refusing would be placing their desires over the well-being of the city as a whole. Therefore, they’ll “descend” back into the cave to educate those still within it about the best, most moral ways to live their lives and run society.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Plato's "The Republic" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Republic summary:

- Plato’s concept of justice

- Why living a moral life is good for its own sake

- How later philosophers interpreted and responded to the ideas in The Republic