This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Inspired" by Marty Cagan. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

How do you test new products? What are the four major risks that need to be addressed?

A crucial part of the product development and discovery process is new product testing. There are four major risks that need to be addressed during these tests: value, usability, feasibility, and business viability.

Keep reading to learn how to assess the four risks of new products.

Testing New Products

New product testing is the final step in the discovery process—it’s meant to once and for all separate the good ideas from the bad. It should address the four risks of product discovery:

- Value: Does the product have a market niche?

- Usability: Can users understand the product?

- Feasibility: Can the company reasonably build the product?

- Business viability: Does the product make sense for our larger business strategy?

The answer to all of these questions must be “yes” before a company moves on to creating the product. A company can’t know whether the product has a market niche, or whether people will buy it, with 100% certainty—which is why some products flop. But tech companies can validate many ideas during the discovery process. Most of these ideas won’t work out, but failures won’t be a large blow if companies use prototypes and focus groups to limit the time and resources spent. Transparency and communication are critical to the testing process as well—a sales executive might realize that an idea doesn’t meet the standard of business viability, whereas an engineer might conclusively say that building a product isn’t feasible.

1. Value

Determining whether a product has value or a market niche (commercial viability) is one of the most important tests. Customers will generally only buy a new product if it’s significantly more valuable than what they’re currently using. There are three ways to test for value: the fake door demand test, the qualitative value test, and the quantitative value test.

Fake Door Demand Test

The fake door demand test determines whether there’s a demand for your product. The test works like this: You add your idea for a product to your company’s already-live system. If it’s a new feature on your company’s app—you’d put the feature link where it would be if you were to launch it. But clicking on it would take the customer to a page recruiting test subjects for the feature. Similarly, for a new product, you’d build a landing page that links the potential customer to a recruiting page. You can track the number of clicks on the feature or product to see if demand exists, and you can find some new test subjects.

Qualitative Value Test

This type of value testing will show why a product has value or doesn’t. If the latter is the case, it will also show what a company can do to fix its value problem (if it’s fixable). You’re not proving that your product is good here. Rather, you’re learning quickly. This type of testing, according to Cagan, is the most important part of the discovery process. Here’s how it works:

- First, interview the test subjects to make sure that they have the problems that you screened them for, and determine what might convince them to switch from their current product to yours.

- Then, perform a usability test (explained in the next section) to see whether customers can figure out how to use your product.

- Next, determine whether they perceive your product as having value:

- Ask whether they’ll buy the product on the spot. You won’t sell it because it’s a prototype, but you’ll learn whether they’re willing to pull their wallet out for it.

- Ask how likely they’d be to recommend the product to their friends (use a 1-10 scale).

- Ask whether they’d spend time on more tests.

It’s almost certain you’ll get different answers from different test subjects. Figure out why they feel differently from one another. Product managers should be at every qualitative test to help understand the differences. Some people are bound to be uninterested in the product. But if most test subjects aren’t interested, it might not work. Even if many test subjects are interested, it’s useful to listen to those who aren’t so you can understand what to fix.

Quantitative Value Test

The third type of value testing—quantitative testing—is generally done with live-data prototypes, which allow the company to acquire enough data for statistically significant results. While qualitative testing is about learning, quantitative testing is about building evidence. Generally, larger companies do more quantitative testing because they have more resources to do so and they’re more risk averse. They may also have more site traffic to build their quantitative tests around.

The best type of quantitative test is an A/B test. In this test, 99% of users use the “A” version of the product, or the version that’s already publicly available. The other 1% uses the “B” version, or the product that’s in the discovery stage. The company then collects data on the behavior of the two groups.

Some companies that don’t have enough traffic for an A/B test will use an invite only test. This is similar, but instead of selecting a random and small group of users, they invite users to use the “B” version. Unfortunately, though, the data isn’t as reliable because subjects opted in to using a new version.

Advanced analytics have changed the way companies can go about their product discovery. They help companies measure progress and understand much more about customer behavior, and for this reason, more companies are using them.

(Shortform Note: Michael Lewis’s Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game explores the differences between qualitative and quantitative analytics through the lens of baseball. Read the Shortform summary here.)

2. Usability

Usability is the second of the four risks that testing must address in the discovery process. Usability testing tests whether users understand how to use your product by putting an early prototype in front of them and asking them to use it. This gives companies an idea of how potential users approach the product, how they understand the UX design, and whether they have functionality concerns that you may not have spotted. The usability testing process is as follows:

First, recruit a group of test subjects. If you have a customer discovery program (as described earlier), use that for your subjects. Otherwise, you can advertise via Craigslist or your company website, or send emails to an email list for current customers. Trade shows can also be useful for finding test subjects. Generally, especially if you’re doing the testing in your office, you’ll pay the subjects for their time.

Next, prepare the test. As you might expect, most usability testing happens using a high-fidelity user prototype, because the test subjects should have most of the experience of using the product before they make a judgment on whether or not they understand it.

Before administering the test, decide what you want out of it and what you want the test subjects to do. If you’re designing a betting app, for example, you’ll look for test subjects navigating the app, placing (fake) bets, depositing money, and so on.

One person should administer the test and another should be responsible only for notetaking. Once again, the product manager, product designer, and an engineer should be present to see the results. If you don’t have an office that works for this sort of testing, it’s easy to do in a coffee shop, or even in your test subject’s office. This can sometimes even be useful, because you’ll better understand the computer/phone setup that your test subject has and how they’d interact with your product on their own time.

Now, you’re ready to administer the test. Here are some steps to do so:

- Tell the users they’re using an early prototype and not the real product.

- Ask the users whether they can tell just from the first (landing) website page what your product is/does. This is useful information for the product designer.

- Make sure that during the test, the subjects are only using the product and not looking for ways to critique it. The testing environment makes people think they should provide critiques, but you’re just looking to see how they’ll use the product.

- Look for whether the user:

- Used the product with no trouble.

- Had a little trouble but ultimately figured out the product.

- Couldn’t figure out the product.

- Don’t help the test subjects figure anything out, but if you feel the need to talk to them, simply ask what they’re doing with the product. This can give you some insight into how they’re understanding it.

- Look for places the users are having trouble or places where they give up. These are the spots in the product to fix.

After the test, a team member should immediately write a summary of what happened using the notes. The more information from the test the better.

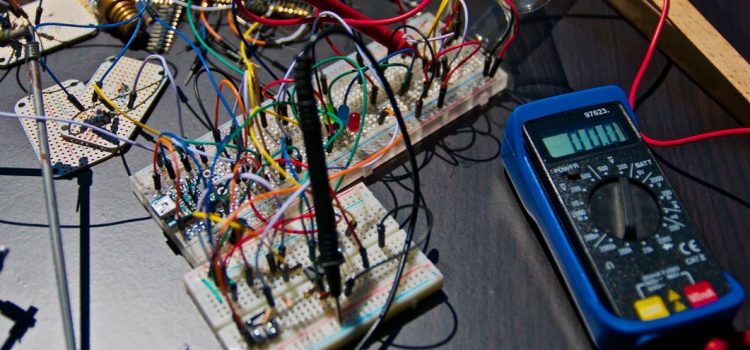

3. Feasibility

The third risk to be explored by testing is feasibility, or whether engineers can actually build a product. Feasibility testing asks engineers to determine whether it is possible for a product to be built either by building a feasibility prototype or by building enough of the product that they are confident they can build the rest. Feasibility testing is also asking whether the current engineers on the team have the skills to do so, whether the company has enough time and resources to build the product, whether the product can be scaled, and even whether the company has the raw materials to build the product if it’s hardware.

Feasibility testing is essential because if a product team devotes significant time and energy to a product and then finds out it can’t be completed, they’ve wasted all of that time.

At this stage in discovery, most engineers will decide that the answer to the above is “yes, this is feasible.” Occasionally, though, if engineers are not sure if something is feasible, they need time to investigate it. In this instance, engineers build a feasibility prototype to answer any outstanding questions. As we’ve learned, these prototypes don’t take much time or energy generally, but the product manager still has to decide whether it’s worth the effort. Generally, the answer will be yes, and often, while considering the question of feasibility and dealing directly with the product without other distractions for a day or two, engineers come back not only saying it’s feasible, but offering ideas to make the product better.

4. Business Viability

The fourth risk that testing explores is business viability, or whether the product will be profitable. This is the final hurdle before moving on with product creation. The product manager shows departments throughout the company the business model they have created of the product, and these departments in turn analyze the business model for any potential problems. If they don’t see any, they will sign off on the project. Many stakeholders need to sign off before a product has business viability—here are some of the most common.

Marketing

The marketing department is concerned primarily with driving sales. They will be looking for a product that they can easily explain to customers and one that will have a lasting impact and relevance in the marketplace.

Sales

While the marketers are the ones trying to drive people to the product, the sales team are the ones getting pen to paper (or hand to credit card or keyboard) and completing sales. Especially if your company has a direct sales team, they will be interested in whether they have a product that they can get off the shelves and one that they can make good money on.

Customer Service

Product managers should be aware of a company’s customer success strategy while they are building their product. A customer success strategy is how companies have decided to help their customers through using the product. Some companies use a high-touch strategy, meaning that they provide significant support for their customers, while others provide a low-touch strategy, which is hands off. The product needs to fit with the company’s strategy.

Finance

The finance department will ask whether the company can afford to produce and sell the product. Additionally, they’ll have a good sense of investor expectations—it’s useful to talk through the costs associated with the product (and the benefits) with someone in the finance department.

Legal

Project managers must address legal concerns before they can launch a product. Companies that don’t consider whether there are potential privacy violations, intellectual property violations, or compliance violations may be opening themselves up to legal action that can cost the company money and reputation.

Security

The product manager needs to be clear that the product is secure before launch. The easiest way for a tech company to enter into a downward spiral is to compromise the security of its users’ information.

Leadership

Finally, the product manager needs to get approval from leadership. The leadership of the company has to be satisfied that all of the previous business viability conditions have been met before they give their sign-off. Hopefully, they’ve been involved for much of the process, but no matter what, they’re always aware from experience of the risks associated with launching a product.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Marty Cagan's "Inspired" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Inspired summary :

- A two-step plan for creating and sustaining successful technology products

- Why product managers are so important in product development

- How to avoid some of the biggest pitfalls that most tech companies fall into