This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "No Bad Parts" by Richard C. Schwartz. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What exactly is a self? Do we have one self or many?

In psychology, the “self” used to be thought of as singular, unified, and consistent—but this idea is no longer common. While many theories of self exist, most acknowledge that one’s self is complex and multi-layered, a shifting amalgamation of thoughts and experiences informed by various contexts.

Here’s why each of us has multiple selves, according to psychiatrist Richard Schwartz.

Multiplicity Theory

The pervasive theory of the self in psychology proposes the existence of one mind, from which all thoughts and feelings emanate. This theory suggests that everything we think, feel, imagine, and desire comes from a singular, unified self.

Schwartz argues that the “mono-mind” conception of self is not only false, but damaging. The problem with this paradigm, according to Schwartz, is that if we’re only one thing, then any shameful, violent, or otherwise socially unacceptable thought or emotion challenges our core identity. We then feel obligated to suppress or control those parts of who we are, resulting in feelings of self-hate, shame, and anxiety.

(Shortform note: While many psychologists agree that having socially unacceptable or “intrusive thoughts” is a universal experience, the idea of multiplicity is still widely pathologized and most often associated with the identity disorder spectrum, from identity disturbance to dissociative identity disorder (DID).)

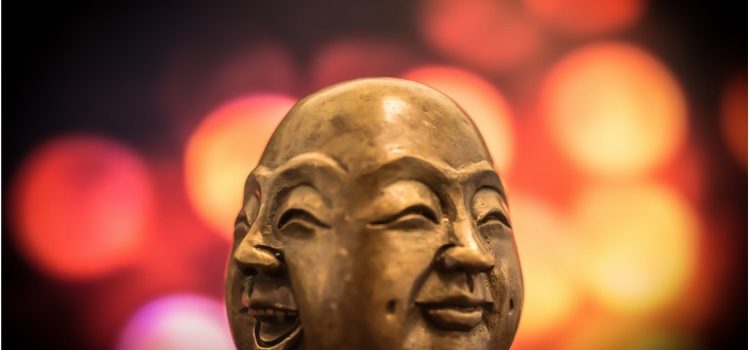

He proposes an alternative concept of self in which we all have a core Self and a “multiplicity” of parts inside of us, none of which are inherently bad, and all of which want what’s best for us. This concept of internal multiplicity flies in the face of longstanding cultural norms that frame the idea of multiple selves as a product of emotional damage or mental illness (for example, Dissociative Identity Disorder, formerly known as Multiple Personality Disorder). Schwartz explains that honoring, instead of pathologizing, our multiplicity allows us to see every part of who we are as deserving of attention and compassion.

(Shortform note: Schwartz is not the first to theorize the idea of multiplicity in psychology. In 1923, neurologist Sigmund Freud introduced his theory of personality, proposing that the mind is divided into three parts—the id, ego, and superego—which work together to form an individual’s personality and influence behavior. Similarly, in the 1950s, Eric Berne introduced the idea of Transactional Analysis in which he suggested that human psyches move between three different “ego states”: the Parent, the Adult, and the Child. So while Schwartz applied the concept of multiplicity in new ways, the concept of multiplicity was not new to psychology when he developed IFS.)

Schwartz emphasizes that our internal parts aren’t metaphors or symbols but beings with their own complex thoughts, emotions, and motivations. If you haven’t explored this concept before, it can be hard to imagine. Imagine you’re debating whether to attend a party. You might notice that one part of you really wants to go–it says you’ll have fun and meet new people–while another part of you might caution you to stay home because you probably won’t know anyone and will feel out of place. These two internal monologues are different internal parts that have conflicting motivations: The first one wants to help you expand your horizons, while the second wants to protect you from rejection.

| IFS vs. Dissociative Identity Disorder For many people, their only understanding of the concept of “being multiple people” is in the context of Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID). So how is the concept of multiplicity in IFS and in DID different? Dissociative Identity Disorder is widely accepted by psychologists as a mental health condition in which people have separate identities (or alters) that act and think independently from one another. People diagnosed with DID often have extended periods of dissociation resulting in lapses in memory or periods where they can’t remember what happened. Unlike alters, the parts described in IFS are subpersonalities of our identity that show up in different scenarios. They aren’t separate, but parts of a related network that make up the whole. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Richard C. Schwartz's "No Bad Parts" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full No Bad Parts summary:

- A detailed look at IFS—a psychotherapy model that challenges the idea of a unitary mind

- Why it's normal to have conflicting voices in your head

- What IFS therapy looks like in practice and its benefits