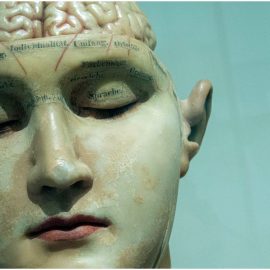

What causes us to make immoral decisions that hurt other human beings? How does the human tendency to seek social approval jeopardize morality?

At its heart, human nature is inherently good and moral because morality has survival value. However, we often make immoral choices because we irrationally base our decisions on what other people are doing rather than on what we think is right.

Keep reading to learn about the psychology behind moral decision-making.

Failing to Make the Moral Choice

According to Peter Bevelin, the author of Seeking Wisdom, one reason we fail to make moral decisions is that we’re afraid having an unpopular opinion will invite criticism. For example, imagine one of your colleagues makes a sexist comment during a meeting. You avoid speaking up because you don’t want others to criticize you for being overly sensitive or disloyal.

(Shortform note: There’s a term for our tendency to conform to others’ expectations of us and make immoral choices: the banality of evil. It’s the idea that ordinary people can do extremely immoral things when there’s pressure to conform or to follow the orders of authority figures. Philosopher Hannah Arendt proposed this idea to explain why ordinary Germans became complicit in the atrocities of the Holocaust.)

The Evolutionary Origins of Our Failure to Make Moral Choices

Bevelin argues that throughout our evolutionary history, our habit of following others’ behavior helped ensure our survival. Cooperating with other people increased our chances of avoiding pain and seeking pleasure. Our hunter-gatherer ancestors hunted in groups, collaborated on building shelters, and treated each other’s wounds. These ancestors learned to strive for social acceptance since inclusion in the group had many benefits. They learned to fear social exclusion, as it would reduce their access to the benefits of group cooperation.

(Shortform note: While Bevelin emphasizes how following and cooperating with others increased our chances of survival, the opposite behavior—distrusting others—also has evolutionary value. In Talking to Strangers, Malcolm Gladwell notes that distrusting others’ intentions helps us notice when others are trying to take advantage of us. However, he adds that we nonetheless evolved the tendency to trust others by default because mutual trust and transparent communication aided our survival significantly more than constant skepticism did.)

A Solution: Recognize the Benefits of Making the Moral Choice

Although our evolutionary past hard-wired us to prioritize social inclusion over independent moral thinking, we can counteract this tendency with rational thinking. Bevelin offers a strategy from Warren Buffet that can motivate you to make the moral choice—even if it’s the unpopular choice.

When you’re faced with a moral choice, ask yourself if you’d be able to live with a critical journalist writing a front-page story about your decision. For instance, consider if you’d be able to live with everyone you know reading this headline: “Worker Fails to Call Out Colleague for Sexist Comment, Claiming She ‘Hoped Someone Else Would Do It.’”

| Make the Moral Choice by Leveraging Your Desire for Social Approval Bevelin doesn’t explain why Buffet’s front page test works, but we can infer that this strategy leverages our ingrained desire for social approval, using it to compel us to do what’s right. This strategy expands our decision’s audience to anyone we imagine reading our front-page story. We may then fear their disapproval of our immoral actions and instead do something moral that they’d approve of. Other experts also offer strategies that, like Buffett’s, utilize our natural desire for others’ approval to motivate us to make the moral choice. For instance, some experts recognize that we’re susceptible to following the commands of authority figures, and these figures can sometimes compel us to make immoral choices. You can overcome this tendency by changing your allegiances: Create distance between yourself and the figure of authority, and align yourself instead with victims. That way, you’re more likely to act morally to gain victims’ approval, rather than act immorally to gain the authority figure’s approval. |