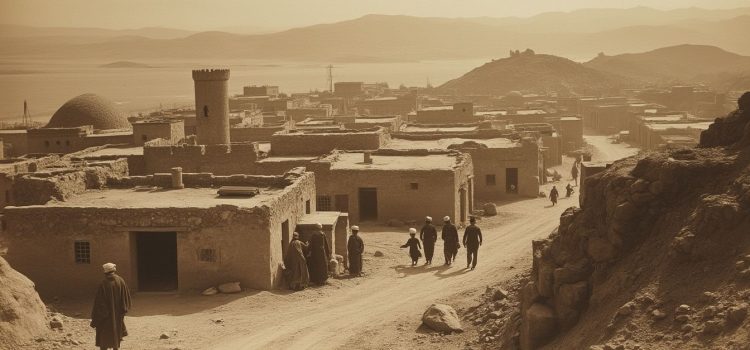

What led to the dramatic reshaping of the Middle East between 1918 and 1923? How did European powers’ decisions after World War I influence the conflicts we see in the region today?

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire led to the emergence of new nations and boundaries. European powers took charge of reorganizing the region through a series of agreements, but their decisions often disregarded local cultures and preferences and sparked over a century of conflict.

Keep reading to learn about the Middle East after WWI from the perspective of David Fromkin in A Peace to End All Peace.

The Middle East After WWI (1918-1923)

By the end of the war, the Central Powers had lost and the Ottoman Empire was dismembered. (Shortform note: The war ended by degrees, just as it began. The Ottoman Empire surrendered in October, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire ended in November. With no allies left and facing unrest from its population, Germany signed an armistice in November 1918. The war officially ended with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919.)

Fromkin discusses the vast changes in the Middle East after WWI, explaining that many countries we think of today as part of the region emerged from the postwar remains of the Ottoman Empire. The period between 1918 and 1923 was one of intense negotiations between European powers as well as unrest and bids for independence from Middle Eastern countries. It culminated in what Fromkin calls the 1922 settlement, a series of agreements delineating new borders for the Middle East. However, Fromkin argues that Europe’s agreements failed to ensure lasting stability in the region it tried to govern.

(Shortform note: Europe also failed to ensure lasting stability within itself. The precarious peace settlements after World War I led to a second global catastrophe a few decades later. World War II also involved the Middle East, with key battles taking place in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon.)

We’ll discuss why Europe failed to stabilize the Middle East after the war. Then, it will explore how Europe reorganized the region and how those agreements defined the lay of the land in today’s Middle East.

Essential Context: Why Europe Failed to Stabilize the Middle East

While Britain and France thought they had solved the Middle Eastern “problem” of who would rule the region after the Ottoman collapse, they created lasting conflict and instability. We’ll describe two of Fromkin’s explanations for Europe’s failure.

Europe’s Self-Centered Choices

Fromkin argues that European leaders based the Middle Eastern boundaries they drew on their interests. They disregarded local preferences, leading to legitimacy issues and opposition. People didn’t identify with their new nationalities, and neighboring countries had competing claims to the lands and peoples the Europeans reshuffled.

In addition, Europe imposed a Western state system on the Middle East without considering local cultures. Fromkin claims European policymakers didn’t understand the regions they were trying to govern. They lacked accurate maps and cultural context about regional divisions and politics.

(Shortform note: Fromkin’s description of Europe’s disregard for local cultures, context, and preferences in the Middle East illustrates Edward Said’s concept of Orientalism. Orientalism is the framework through which Western policymakers have defined Islamic societies. Calling the Middle East “the Orient,” they have framed this region as fundamentally different, exotic, dangerous, and unchanging. This concept of a strange East incapable of progress enabled the West to think of itself as superior and to dismiss regional political movements, like nationalism, as anomalies. Believing the region’s political life was less evolved than Europe’s, Western policymakers decided which states and rulers to establish on behalf of the Middle East.)

New Faultlines in the West

Fromkin explains that the West also reconfigured itself after the war, complicating its ability to stabilize the Middle East. Russia and the US distanced themselves from the Allies during the lengthy period of peace negotiations. This break conflicted with the British goal of sharing the expense and hassle of governing the region.

Sharing the load was important because Europe’s money and manpower were dwindling after the war. Fromkin writes that Allied soldiers were eager to return home, and army occupations were a drain on financial resources. Citizens back home demanded their money be spent rebuilding their countries’ shattered economies rather than governing distant regions. This led Britain to establish puppet governments and rule by proxy to limit the costs of having a physical presence in all the Middle Eastern territories under their influence.

| The End of One Conflict and the Start of Many Others The period after World War I marks the beginning of the end of Western Europe’s imperial dominance. The economic and political chaos—which led to and intensified after World War II—fostered the reconfiguration of the world around the US and Russia. After World War I, while Europe faced the economic turmoil Fromkin describes, the US emerged as a leading force. The victorious Allies, despite winning the war, were economically crippled by the debt they racked up to each other and the US during the war, with the US being the economic winner of the war. Russia’s economy had already collapsed during the war, leading to the Soviet revolution. As it transitioned into the Soviet Union, fears spread across Europe about potential working-class revolutions. The US and the Soviet Union distanced themselves from the Allies but became key players in the Middle East. The Soviet Union consolidated its influence over Central Asia. Meanwhile, the US began its involvement in the Middle East to secure oil access. After World War II, as the region gained independence from Britain and France, US involvement grew to counter Soviet influence, leading to decades of conflict and intervention. |

Key Decision: The “1922 Settlement”

European powers drew up what Fromkin calls the 1922 settlement—a long list of agreements European powers and Middle Eastern leaders arrived at around 1922. The agreements determined which Ottoman Empire territories would become independent countries and which would be absorbed by European empires such as Britain, France, and Russia. The agreements impacted the countries throughout the region, from Egypt—which gained independence—to Afghanistan. We’ll focus on some of the most controversial decisions.

Regarding Russia, the settlement defined its political borders along the Türkiye-Iran-Afghanistan line. Fromkin writes that the Russian proclamation of a Soviet Union in 1922 consolidated its control over Muslim Central Asia, quashing independent movements and integrating the territory into the new Soviet state.

Key Outcome: The 1922 Settlement Unsettles the Middle East

Fromkin describes how Europe reshaped the Middle East post-World War I. Some countries became independent, but Fromkin explains that independence came at a cost, whether it was war or foreign intervention. Greater Syria fell under France and Britain’s direct control, and the European administration of the region led to the creation of several new countries.

We’ll discuss how the 1922 settlement shaped nine Middle Eastern countries and contributed to their instability.

Türkiye

According to Fromkin, the harsh terms Europe imposed on Türkiye as part of the postwar agreements led to the Turkish War of Independence.

Through the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, Europe dismantled the Ottoman Empire and imposed large territorial losses and heavy financial reparations on Türkiye, the empire’s seat of government. The Treaty fueled nationalist sentiment and ignited the Turkish War of Independence, which killed hundreds of thousands of Turkish, Greek, and Armenian civilians. Turkish forces succeeded, leading to the establishment of the Republic of Türkiye and the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, which recognized the borders of the modern Turkish state.

Iraq

The decision to create Iraq by uniting the ethnically and religiously diverse regions of Mesopotamia led to persistent infighting and questioning of the country’s legitimacy. According to Fromkin, the country still grapples with internal conflicts as a result of the rivalries between the Shia and Sunni strands of Islam and with minority ethnic groups such as the Kurds.

Fromkin explains how, after World War I, Mesopotamia became more strategic thanks to its oil reserves. At the same time, it was becoming more difficult for the British to govern it. The population often rose up against the British occupation, resulting in violent confrontations. In 1921, the British government handpicked the first Iraqi king so they could stop governing the region directly while still protecting their commercial interests. However, they chose a Sunni king, which made the Sunni minority into a ruling elite over the Shiite majority population.

During the postwar decision-making period, Europe decided not to facilitate a Kurdish kingdom. Fromkin writes that the discussions on the subject didn’t materialize into any decision, which effectively left the Kurds without a state of their own.

Saudi Arabia and Transjordan (Jordan)

Britain shaped today’s Arabian Peninsula in two ways. They made the Palestinian region of Transjordan into a separate state, and they backed a leader of Transjordan in opposition to the rising leadership of Ibn Saud in today’s Saudi Arabia. We’ll discuss both actions in more detail.

Fromkin explains that Britain’s administrative actions in Transjordan eventually led to the creation of Jordan. To control anti-French and anti-Zionist movements without overextending resources, Britain elevated Abdullah I bin Al-Hussein of the Hashemite royal family to lead Transjordan. This move contradicted Britain’s policy against Jewish settlement near territories led by Arabian leaders, so they separated Transjordan from Palestine to bypass this policy.

Fromkin argues that Britain’s support for Abdullah divided the desert Arabs and created lasting questions about Jordan’s legitimacy. Britain backed Abdullah in the west but tacitly approved Arab political leader Ibn Saud in the east. Ibn Saud embraced Wahhabism, a conservative Islamic movement, to expand his territory, threatening Abdullah’s control.

With British military backing, Abdullah retained some land, but Ibn Saud expanded across Arabia without confronting Britain directly. This rivalry led to the modern borders between Saudi Arabia and Jordan. According to Fromkin, it also encouraged Jordan’s critics to question its legitimacy, since it arguably could not have survived without Britain’s support.

Syria and Great Lebanon (Lebanon)

According to Fromkin, France’s decision to divide Syria-Lebanon into autonomous regions led to conflicts and bloodshed. Arab nationalists opposed French rule and declared Syria-Lebanon independent in 1920. But France was determined not to lose Syria-Lebanon, which was theirs according to Sykes-Picot, and they invaded Damascus.

Between 1920 and 1923, France consolidated its control over the region through military conquest and administrative division. In 1923, the League of Nations confirmed the French Mandate over Syria-Lebanon. During their administration of the region, the French implemented a policy of divide and rule to weaken nationalist movements by worsening sectarian and regional differences. They broke up the region into different administrative areas, making it difficult for the different groups resisting them to collaborate and successfully reject the French.

France divided Syria-Lebanon into several autonomous regions, including Great Lebanon—a precursor to modern-day Lebanon. Fromkin claims that redrawing Lebanon’s borders led to bloodshed in the 1970s and 1980s due to conflicts between the majority Muslim population and the minority Christian groups which were brought together artificially.

Palestine and Israel

In Palestine and Israel, the British government’s decision not to follow through on their promises to either Arabs or Zionists led to a still-unresolved dispute. The British administration committed itself to creating a Jewish home in Palestine without specifying what that meant. Fromkin argues that many British leaders believed it meant an expanded Jewish community within a multinational Palestine under British rule, not a Jewish state. However, the British had given the impression to their Zionist allies that they’d establish a full-blown Jewish state.

Fromkin explains that Zionist leaders felt constrained by the British administration’s wavering stance. They believed that if the British made it clear that the Balfour Declaration was non-negotiable and would be enforced, Arabs would be forced to accept it and even see its potential benefits, like increased economic development in the region.

According to Fromkin, the main obstacle to negotiations among the British, the Jewish settlers, and the Palestinians was the Palestinian delegation’s uncompromising stance. They were worried about losing their land. Some Palestinian groups responded to the increasing Jewish immigration with violence. Deadly anti-Zionist riots broke out against incoming Jewish settlers, leading Britain to suspend Jewish immigration into Palestine temporarily. In addition, Fromkin writes that the British officers in Palestine—not politicians but rank-and-file members of the army—sided with the Palestinians, doing little to suppress the violence. When the British army didn’t react quickly enough to restore order, Jewish militias took up arms to protect themselves.

Finally, Fromkin highlights Britain’s White Paper for Palestine, which Churchill wrote to bring order to the region. The document reiterated support for a Jewish national home in Palestine without making it into a Jewish state. It left Palestinian and Zionist leaders dissatisfied: Zionists wanted more support for their project, while Palestinians wanted to end the project entirely.