This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Distracted Mind" by Adam Gazzaley and Larry Rosen. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What is the marginal value theorem? Why is technology so distracting?

To explain technology’s impact on interference and the brain, The Distracted Mind by Adam Gazzaley and Larry D. Rosen looks to the marginal value theorem. The MVT is used to examine food habits in animals but can be applied to humans’ excessive use of technology.

Find out more about the marginal value theorem here.

Why Does Technology Make Interference More Common?

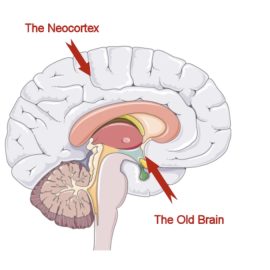

Broadly speaking, the authors argue that technology leads to widespread interference because we’re evolutionarily wired to consume information, and technology provides easy access to such information. They use the marginal value theorem to explain this phenomenon.

(Shortform note: Gazzaley and Rosen don’t explicitly explain why we’re wired to consume information, though they cite an article with a potential explanation. The article’s author argues that information is predictive of resources that are crucial to survival—like food, water, and shelter. For example, sensory information about high humidity in the air might be suggestive of crops nearby. So, because the evolutionary process selects for traits that help us survive and reproduce, it encourages us to consume information that makes it easier to do so.)

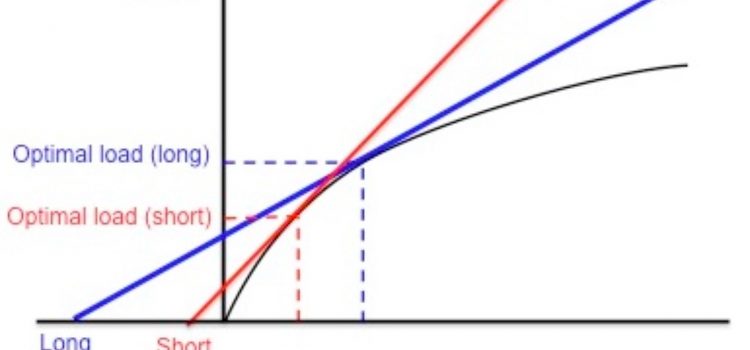

To explain why our drive for information makes us more susceptible to interference, the authors first discuss the marginal value theorem (MVT)—a theory that predicts when animals will shift from one food patch to another to maximize food consumption—and then suggest that its insights can be applied to our information consumption.

The Marginal Value Theorem Applied to Food Foraging

Roughly put, the MVT states that three factors determine when an animal will leave its current food patch and forage elsewhere: the amount of food in its current patch, the ease of access to nearby patches, and the amount of food in those nearby patches. In other words, animals are likely to stay in patches rich with food—especially if nearby patches aren’t easily accessible—but will be quick to leave patches with fewer resources—especially when nearby patches are accessible.

To see how the MVT functions in practice, imagine that you go apple-picking and find a tree full of apples that’s surrounded by barren trees. In this case, you likely won’t leave the tree full of apples until you’ve picked all the apples—the prospects of foraging elsewhere aren’t good enough to justify leaving. On the other hand, imagine that you start picking apples from a rich apple tree in a forest full of similarly rich trees. In this case, you’ll be more likely to quickly leave your current tree once you’ve picked its low-hanging apples because you can easily access more plentiful trees once you’ve picked the accessible apples from your current tree.

| A Deeper Dive Into the Marginal Value Theorem Multiple experimental studies have demonstrated that certain animals’ foraging behaviors conform to the MVT. For instance, one study found that, in a laboratory setting, the foraging behavior of guinea pigs and screaming hairy armadillos matches the predictions made by the MVT. Similarly, a field of study of great and blue tits—two species of birds—found that the birds’ foraging behaviors in their natural environment were roughly in line with the MVT. Nonetheless, other experts have pointed out that the MVT has several shortcomings. For example, ecologist Peter Nonacs has argued that the MVT is too simplistic in its exclusive focus on foraging because it fails to consider other activities that animals engage in concurrently—such as seeking mates and avoiding predators. In turn, he contends that many animals’ behavior does not square well with the MVT, since these other considerations influence their foraging behavior. |

The Marginal Value Theorem Applied to Technological Interference

Crucially, Gazzaley and Rosen argue that the MVT can be adapted to explain our vulnerability to technology-induced interference. Treating different information sources—such as social media, emails, and text messages—as “information patches,” they contend that technology has made us more vulnerable to interference for two reasons:

1) Per the MVT, animals more quickly move to another patch of food when that patch is easily accessible. As we’ve discussed, smartphones, social media, streaming platforms, and work group chats have made new patches more accessible than ever. (Shortform note: Though information is becoming more accessible, another factor complicates the situation—information is also becoming lower quality. For example, experts note that the deluge of information on social media often creates widespread “fake news” because it’s more difficult to verify information when we’re exposed to so much of it.)

2) Per the MVT, animals more quickly move to another patch of food when it becomes too costly to stay in their current patch. In our case, technology has increased the costs of focusing on one source of information by inducing anxiety and boredom when we do.

Regarding the second point, Gazzaley and Rosen point to studies showing that, when students concentrate on work-related screens, their cognitive engagement quickly decreases; by contrast, cognitive engagement spikes when they switch to entertainment-related screens. For example, students writing an essay might quickly become disengaged, causing them to switch to Twitter, where their brains are more stimulated. As Gazzaley and Rosen hypothesize, this quick onset of boredom is likely due to the faster reward cycles associated with media multitasking—for instance, teenagers are rewarded with new information whenever they switch social media apps, which can create boredom when remaining on one app.

(Shortform note: Some experts contend that the concept of boredom is a recent phenomenon. In Boredom, literary scholar Patricia Meyer Spacks argues that the concept of boredom arose in the 18th century as leisure time became more common; she observes that, at the time, boredom was even considered sinful because it allegedly indicated a lack of faith in God. Moreover, she argues that the emphasis on personal experience that accompanies individualism made boredom all the more salient. So, it stands to reason that although technology may have exacerbated boredom, there are multiple causes at work.)

Finally, to illustrate the increased anxiety caused by technology, the authors cite their study of individuals born in the 1990s. They note that of these individuals, approximately half report feeling anxious if they can’t check their text messages every 15 minutes, with similar numbers for other forms of technology, such as social media and email. Moreover, they note that other studies have shown similar results, confirming a link between increased smartphone usage and increased anxiety. In turn, humans are more likely to frequently check their phones—often interrupting other tasks—to mitigate this anxiety.

(Shortform note: Smartphones aren’t the only anxiety-inducing form of technology: Researchers have also found a strong correlation between social media usage and increased anxiety among adolescents. However, the causes behind social media-induced anxiety might differ from those behind smartphone-induced anxiety. Indeed, some experts hypothesize that social media fuels social anxiety in particular because it causes fear of being judged and makes us more self-conscious.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Adam Gazzaley and Larry Rosen's "The Distracted Mind" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Distracted Mind summary:

- How technology has made us more prone to distractions and interruptions

- How to modify your environment to reduce distractions and boredom

- How to minimize your susceptibility to interference and improve cognitive control