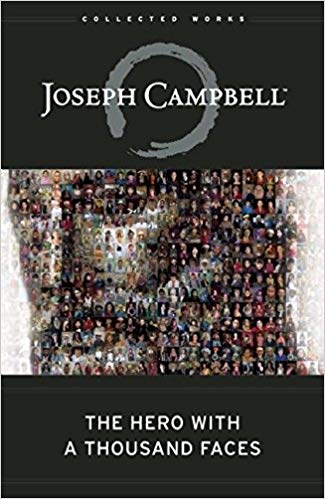

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "The Hero with a Thousand Faces" by Joseph Campbell. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What are some of the most popular Maori myths and legends? How do these Maori legends fit into the template of Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey?

We’ll cover some Maori myths and legends and discuss how they align with stages of the hero’s journey, as laid out by Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

Maori Myths and Legends and the Hero’s Journey

Although the hero’s journey is often filled with daring exploits, the slaying of fantastical monsters, and unions with strange and beautiful goddesses, it is at heart a deeply introspective and inward-looking adventure, one with profound spiritual and psychological implications. We’ll see this through our examination of Maori myths and legends. Through their arduous trial, the hero learns new things about himself or herself and discovers hidden strengths that were dormant within them the entire time—in fairy tales, this is often made literal by the revelation of the hero to have been “the Chosen One” or “the King’s son.” These new (but latent) powers enable a thorough transformation of the hero’s outward being and psyche.

The Monomyth

The core structure of mythology is called the monomyth. It involves three rites of passage—separation, initiation, and return. From the myths of the ancient Egyptians and the medieval Arthurian legend to the Maori myths and legends of New Zealand, the pattern of the hero’s journey usually follows this cycle: a separation from the world he or she has always known (embarking on the quest), gaining some spiritual or other-worldly power, and a return in which they share the boon of the new power with humanity.

There are familiar beats throughout world-legend—the call to action; the initial reluctance of the hero; the aid of a supernatural helper; the crossing of the threshold into the world of the unknown; union with the mother-goddess; the slaying of the father-god; the return to the land of the living; and the sharing of the ultimate boon. We’ll look at how one, in particular, is exemplified in Maori myths and legends.

The Ultimate Boon

In this stage of the hero’s journey, the hero achieves their goal and is reborn as a superior being. This is often shown by the ease with which the hero is now able to obtain the things that they seek.

The Ultimate Boon is variously represented across mythological traditions, including Maori myths and legends—the inexhaustible milk of Jerusalem in the Book of Isiah, the Olympian gods feasting forever on ambrosia, the Japanese gods drinking sake, the Aztec deities of pre-Columbian Mexico consuming the blood of humans. The hero seeks the grace of the gods, their energy substance, their elixir of impenetrable being.

But the gods may also be jealous in guarding the power of this elixir from the hands of the hero. They may only be willing to release it to those who are truly worthy. And sometimes, the hero must resort to trickery to obtain this bounty. This is the case in many Maori myths and legends.

The Pursuit

If the hero has won the Ultimate Boon through trickery or manipulation of the gods, their return home may be marked by a chase as the gods seek to regain the elixir that has been stolen from them.

Sometimes, the hero will use decoys to delay or confuse the pursuer. In one Maori myth, a fisherman’s wife swallows the couple’s two sons. He uses magic to force her to vomit the boys out, then uses other spells to further hamper his ogre/wife. When she goes to fetch water, he causes the water to retreat away from her. When she calls out for the man and his sons in pursuit of them, he causes the trees and huts of the village to speak back to her, causing great bewilderment on her part. This distraction enables the man and his sons to escape in a canoe.

Creation Myths

Creation myths are another kind of Maori myth or legend. All cultures have their creation myths—the stories that tell us how the earth was formed, how we came to be here, and what we are meant to do with our existence. As with the heroic cycle, there are endless variations of the creation myth, but there are common elements throughout.

The universe is an emanation of some sort of divine will from a supreme creative entity. The creator first establishes the frame of the universe, the setting in which all subsequent action will take place. Next, the creator puts living creatures into the frame—often, these creatures have the capacity for self-reproduction or contain within them both the male and female aspects (like Adam, as we’ve seen, in the Book of Genesis).

Maori myths and legends of New Zealand have their variation on this theme. According to their legend, in the beginning, there were two elements—Te Tumu (the male) and Te Papa (the female). The universe was an egg that contained both. When the egg burst, it created three layers of existence, one on top of the other. Te Mumu and Te Papa were at the lowest level, where they created birds, plants, and fish. After several failed attempts, they also created the first perfectly formed man, Hoatu. Eventually, the lowest level of existence became overcrowded, so the humans burrowed their way into the next two levels, taking with them plants and animals, so that man came to inhabit three dwellings. This idea of the cosmic egg is seen in many other mythological traditions, including Japan, Finland, Egypt, and Greece.

After the creation of the initial being, there is the great division, the creation of many from one. Sometimes, the creator actively supervises this process and directly implements the ordering of the universe. In other myths, living beings themselves direct the shaping of the world. The latter scenario usually entails a harsher, more arduous unfolding of events than the former. Often, the created being will need to war with or even slay their creator-parents in order to begin shaping the world, as in the Greek story of the Olympians overthrowing the Titans, or in the Babylonian myth of the sun-god Marduk slaying Tiamat, the terrifying personification of chaos and the abyss. In yet another Maori legend, the cosmic parents (Rangi, the Sky, and Mother Earth) lay so closely on top of one another that the children are unable to be born and escape Mother Earth’s belly. The children conspire to separate their parents, vaulting the Sky up high while pressing nurturing Mother Earth down to the ground.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "The Hero with a Thousand Faces" at Shortform . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Hero with a Thousand Faces summary :

- How the Hero's Journey reappears hundreds of times in different cultures and ages

- How we attach our psychology to heroes, and how they help embolden us in our lives

- Why stories and mythology are so important, even in today's world