This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Story of My Experiments with Truth" by Mahatma Gandhi. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

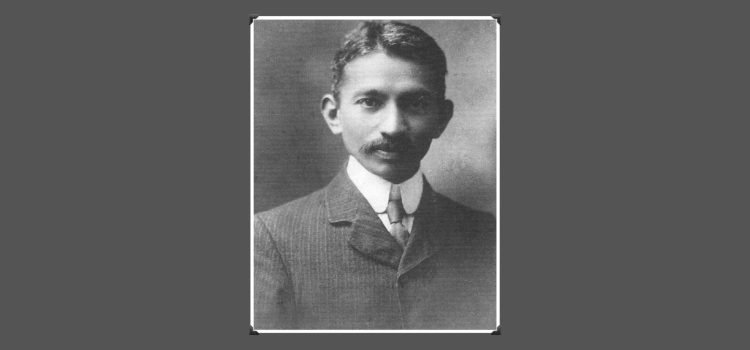

How did Mahatma Gandhi’s journey as a civil rights leader begin in South Africa? What steered him toward a fight against discrimination?

For Mahatma Gandhi, South Africa offered a transformative experience. He encountered racism firsthand and became an advocate for Indian rights. His time there laid the foundation for his later work in India.

Keep reading to discover how Gandhi’s South African years molded him into the leader we remember today.

Mahatma Gandhi in South Africa

For Mahatma Gandhi, South Africa wasn’t part of the career plan. In his autobiography, he relates that he passed his law school exams in London on June 10, 1891, and he was on a ship back home to India by the 12th. Back in India, Gandhi didn’t have much success as a lawyer. He was shy and felt uncomfortable charging his clients for his work. His brother, who’d paid for his education, worried that Gandhi couldn’t contribute to the family’s finances.

(Shortform note: Some of the traits that became part of Gandhi’s leadership style also made it difficult for him to practice law. As he shares in his autobiography, he was so shy that his first court appearance was a disaster because he couldn’t get a single word out in front of the judge. But he transformed that shyness into soft power as he came into his own as a leader. He also had revolutionary views about the legal profession, even by today’s standards: Elsewhere, he wrote that lawyers and doctors should receive a salary from the government instead of charging fees to their clients or patients. He believed that would ensure everyone received quality legal and medical services, regardless of how much they could afford.)

Amid these worries, Gandhi received a job offer in South Africa from one of his brother’s wealthy business partners. The job was to provide legal counsel to an Indian-owned company. The offer was enticing: It paid well and offered the chance to leave India and have new experiences.

Despite his excitement for this new adventure, Gandhi says he was sad to say goodbye to his wife once again, especially as they’d welcomed their second baby since his return from England. So, when he set off to South Africa in April 1893, he was filled with both excitement and sadness.

(Shortform note: Gandhi’s choice to move to South Africa without his wife and children was an example of him putting his career—whether as a lawyer or as a public leader—before his family. Gandhi’s biographers found that his two eldest sons had a difficult relationship with him, even becoming estranged at one point, as a result of the way Gandhi prioritized his pursuit of Truth and justice over being an involved father and husband.)

Experiencing Racism

Gandhi’s experience in South Africa was eye-opening. He experienced racism as an immigrant of color in a European colony. He narrates several noteworthy experiences, including:

- Suffering discrimination on the train. Due to his race, Gandhi couldn’t travel first class. On his first train trip, he was kicked off the train for complaining. He completed the trip by coach, and the coach leader hit him when he refused to sit outside.

- Being referred to as a “coolie barrister.” The Indian community was made up of several cultural, geographic, and religious groups, but the Europeans referred to all Indians as “coolies,” a derogatory term for Indian laborers.

| Gandhi’s Attitude Toward Black South Africans Gandhi’s critics note that the native population of South Africa faced the same or worse racism, but Gandhi didn’t seem to care as much about their suffering as he did for that of his fellow Indians. In fact, critics argue he participated in it. For example, while Gandhi resented being called a “coolie barrister,” he used the derogatory term “kaffir” to refer to Black South Africans. Additionally, he thought Indians should have the same freedom of movement as the Europeans, but he didn’t want the same for the native population. For example, the post office in South Africa had separate entrances for Blacks and whites—and Indians had to use the entrance for Blacks—but Gandhi fought for Indians to have a separate entrance instead of advocating for integration that would benefit Black South Africans. |

Starting Public Work

Gandhi’s experiences of discrimination led him to become an activist for Indian national dignity. During his time in South Africa, he became a leader of the Indian community. After seeing they were divided along religious and ethnic lines, he advocated for coming together as Indians. He proposed establishing the Natal Indian Congress to bring the problems Indian settlers faced to the authorities, and he volunteered his time and effort for this cause.

These are two of the key moments of Gandhi’s leadership journey in South Africa.

The Natal Franchise Bill

In 1893, the Natal Legislative Assembly proposed the Franchise Bill to take away Indians’ voting rights. Gandhi and his friends drafted a petition and collected signatures opposing the bill. It passed, but Gandhi argues that their resistance united the Indian community in their commitment to defending their political rights.

The £25 Tax

In 1894, Gandhi advocated for the rights of Indian indentured laborers in South Africa. These laborers were taken to South Africa to work in sugarcane farming on five-year contracts, after which they were free to do other work and purchase land. Many had become independent farmers and merchants. However, Gandhi says that the Europeans in South Africa resisted their competition in trade and rejected the Indians’ lifestyle, from their hygiene habits to their religion.

To stop former indentured laborers from working freely in Natal, the government enforced a yearly tax of £25 on any contracted Indian laborers who stayed in South Africa to work independently. After the Natal Indian Congress campaigned against the tax, the government reduced it to £3.

| The Shared History of Indians and South Africans The origins of Indians in South Africa date back to the Dutch colonial era when Indians arrived as enslaved people in 1684. The Indian community in South Africa grew through indentured laborers arriving in the 19th century and later as free Indians seeking new opportunities. The political struggles against discriminatory laws helped forge a common South African Indian identity, with organizations like the Natal Indian Congress playing a key role. The movement for national dignity in South Africa also contributed to the push for Indian independence. And decades later, a free India contributed to the dismantling of apartheid in South Africa: India confronted the racist South African government and advocated for African sovereignty at the United Nations. Today’s Indian South African community maintains its cultural ties to India, as well as the religious diversity that characterized it in Gandhi’s time. Many Indian South Africans still speak Indian languages such as Hindi and Gujarati, and they still practice their ancestral religions, including Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, and Sikhism. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Mahatma Gandhi's "The Story of My Experiments with Truth" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Story of My Experiments with Truth summary:

- Gandhi’s life story from childhood until adulthood

- How Gandhi became a world-famous activist

- A look at Gandhi’s commitment to a nonviolent, austere lifestyle