This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Story of My Experiments with Truth" by Mahatma Gandhi. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

How did a simple piece of clothing become a symbol of Indian independence? In what way did Mahatma Gandhi use everyday items to challenge British rule?

Mahatma Gandhi’s Khadi movement was a powerful strategy in India’s fight for freedom. By encouraging Indians to make their own clothes, Gandhi aimed to boost economic autonomy and national pride. This grassroots approach laid the groundwork for future campaigns, including the famous Salt March.

Discover how Gandhi transformed ordinary objects into extraordinary tools for change.

Gandhi’s Khadi Movement

Mahatma Gandhi’s Khadi movement was part of his efforts for India to become less dependent on the British Empire. Gandhi’s activism gradually led him to the conclusion that they needed to be free of British rule. However, India’s economy was tied to the British Empire, and political independence would require economic autonomy, too.

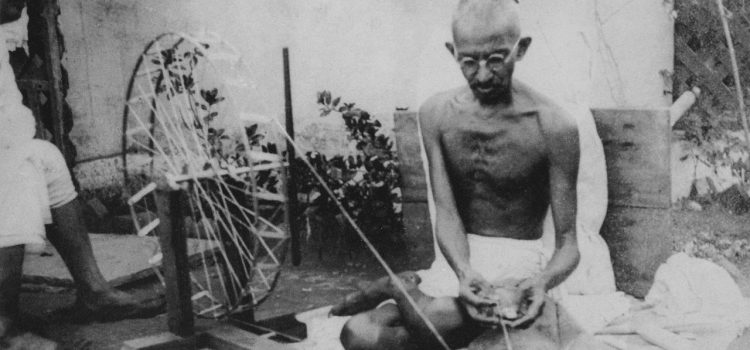

Gandhi believed that one way for Indians to become autonomous was to start making their own clothes instead of relying on mills that traded with the British and imported much of the cotton used in India. Gandhi saw the khadi, a traditional Indian garment made of spun cotton, as the perfect vehicle for Indians to exercise their autonomy. Women could make khadis at home using spinning wheels, and it would be a source of income for them. In addition, it would invigorate the national textile industry, which would have to supply enough finely spun cotton for them to make their khadis. As part of his khadi activism, Gandhi learned to use the spinning wheel and dressed only in Indian-produced khadis.

| The Power of Everyday Things and Regular People The Khadi movement, which began in 1918, was a precursor for one of Gandhi’s most well-known Satyagraha campaigns: the 1930 Salt March (also known as the Salt Satyagraha). The Satyagraha movement was a form of peaceful opposition to the British Empire’s mistreatment of Indians. The term Satyagraha combines the Sanskrit words “sat” (truth) and “agraha” (firmness). Both the Khadi movement and the salt march focused his activism on a specific material that people needed for daily life, using it to highlight the injustices the government was committing and the power of regular people to take back economic control through organized action. In Salt, Mark Kurlansky explains that the British government established a monopoly over salt made by Indian saltworks, requiring Indian salt producers to sell all their salt to the British. Indian salt harvesters rebelled against this monopoly in 1817 by attacking British-controlled saltworks in India. Indian resistance to Britain’s control of salt production reached new heights in the early 1900s when Indians grew upset about the high tax Britain required them to pay on salt. The Indian Legislative Assembly demanded Britain reduce this tax, but Britain refused. In response, Gandhi and his followers walked nearly 250 miles along the Indian coastline, gathering sea salt—illegal under British law. The campaign worked: In the early 1930s, the British signed a pact promising to release political prisoners and permit Indians to collect sea salt. According to Kurlansky, this pact and Gandhi’s campaign paved the way for Indians to secure their independence in 1947. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Mahatma Gandhi's "The Story of My Experiments with Truth" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Story of My Experiments with Truth summary:

- Gandhi’s life story from childhood until adulthood

- How Gandhi became a world-famous activist

- A look at Gandhi’s commitment to a nonviolent, austere lifestyle