This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Story of My Experiments with Truth" by Mahatma Gandhi. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What does ahimsa mean, and how did Mahatma Gandhi apply it to his life? Can we truly avoid causing harm to others in our daily existence?

For Mahatma Gandhi, ahimsa goes beyond simply avoiding violence. It encompasses kindness, empathy, and a deep respect for all living beings. Gandhi’s approach to nonviolence influenced his daily choices, from his diet to his political activism.

Read more to explore the complexities of ahimsa and how it shaped one of history’s most influential figures.

Mahatma Gandhi on Ahimsa (Nonviolence)

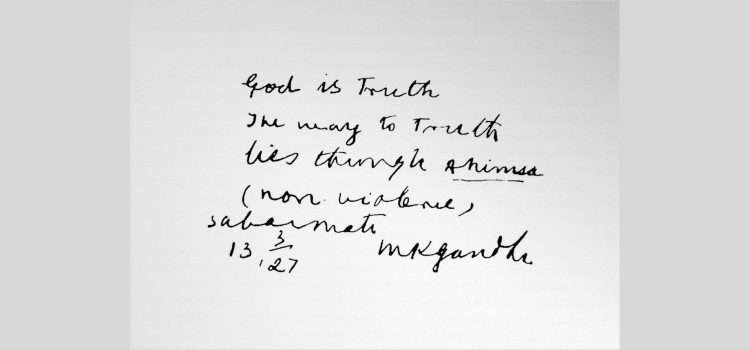

According to Mahatma Gandhi, ahimsa (nonviolence) is the only way one can reach Truth because violence is antithetical to Truth. Gandhi explains that humans can’t avoid causing harm—himsa—to others. For example, we harm animals and plants to eat, and we participate in societal himsa, like war.

We’ll first discuss how for Gandhi, practicing ahimsa meant being kind and not harming living beings. Then, we’ll explore how Gandhi handled a situation when it was impossible to be completely free from himsa.

Practicing Ahimsa

Gandhi sought to practice nonviolence in every aspect of his life, including the following ways.

Nursing the sick and wounded

Gandhi enjoyed taking care of others. He believed this service should be provided gladly—not by obligation. He happily nursed family members and strangers when they were sick or hurt.

Not harming insects or dangerous animals

Gandhi believed in protecting the lives of all living creatures. For example, he founded an ashram, a home for families who wanted to practice ahimsa and live simply off the land. There were snakes on the land, but he never allowed anyone to kill them, even though they lived in tents with young children while they built their houses. The snakes never bit them, which Gandhi attributed to God’s protection.

Being a strict vegetarian

Safeguarding animals also meant not eating meat. Gandhi was raised vegetarian, and he later decided to stop eating eggs—which he equated to eating meat. He also stopped drinking milk due to the violent way farmers extracted it from animals.

| The Connections Among Ahimsa, Empathy, and Mental Health It’s possible that Gandhi had depression, and this illness may have played a role in his commitment to ahimsa. In A First-Rate Madness, psychiatrist Nassir Ghaemi argues that Gandhi experienced depressive episodes throughout his life and that his struggles with this illness gave him the necessary empathy to cultivate his nonviolent approach. Ghaemi highlights Gandhi’s approach to campaigning for India’s independence from British rule, in which he encouraged his followers to understand their enemy’s perspective. This connection between depression and empathy was arguably present in Gandhi’s efforts to avoid himsa. He explains in his autobiography that he contemplated suicide as a teenager because he felt trapped by the restrictions adults imposed on him. He ate poisonous seeds but changed his mind before eating enough to make him seriously ill. It’s possible that the despair he felt made him feel others’ suffering deeply and practice ahimsa in his everyday life, such as nursing others or committing to a strict vegetarian diet. However, Gandhi’s empathy seemed more present in some of his choices and beliefs than in others. For instance, he failed to empathize with the children in his ashram who might have been seriously hurt by the snakes he refused to kill. |

Dilemmas of Ahimsa

Despite his profound commitment to ahimsa, Gandhi admits his efforts were imperfect. For instance, he describes the challenges of practicing ahimsa when volunteering for the British Empire’s ambulance service during the South Africa War and World War I. (Shortform note: Gandhi refers to the South Africa War as the Boer War because it pitted the English and the Boers—early European colonizers of South Africa of Dutch, German, and French origin—against each other for control of what we know today as South Africa.)

Gandhi explains that he was caught between two duties: pursuing ahimsa and improving the situation of his people. Pursuing ahimsa would’ve meant trying to stop the conflict, which he felt he wasn’t strong enough to do. Simply staying out of the conflict wouldn’t count as practicing ahimsa because, by living under the protection of the British Empire, he was already participating in its violence.

Since he was already involved in the himsa, he used the opportunity to further his goals for India. He believed that volunteering in the war would help him improve the situation of the Indian people. At that time, he thought that being part of the British Empire was good for India and that the British government would treat Indians better if they supported the war.

| Facing Moral Dilemmas With Integrity Gandhi’s actions when facing the dilemmas of ahimsa are an example of practicing personal integrity. In The Six Pillars of Self-Esteem, Nathaniel Branden explains that when you act with integrity, your behavior reflects your values. You might not choose the perfect option every time, Branden notes, but you still strive to find and follow the option that best reflects your values. If your values point to opposing behaviors, you weigh your options and select what seems best. This is what Gandhi did when he was confronted with his options regarding Britain’s wars. He weighed them and selected the one that aligned best with his search for morality and justice. Branden also cautions that you can only choose to live by your values—to practice integrity—in situations you can control. As such, it’s important to understand the difference between what you can and can’t control. For example, Gandhi couldn’t control whether Britain started or ended a war, or the fact that he was, as a British subject, participating in the war whether he agreed with it or not. However, he could control how to participate. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Mahatma Gandhi's "The Story of My Experiments with Truth" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Story of My Experiments with Truth summary:

- Gandhi’s life story from childhood until adulthood

- How Gandhi became a world-famous activist

- A look at Gandhi’s commitment to a nonviolent, austere lifestyle