This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Caste" by Isabel Wilkerson. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

In what ways are the lowest caste often mistreated in hierarchical social class systems? What are some examples of mistreatment from United States history?

In order to maintain their power, the dominant caste will often mistreat the lower castes in order to keep them in their place and maintain power. Two major ways they go about doing this are by giving the lower caste members menial and subordinate tasks, and by terrorizing them physically and psychologically.

Continue reading to understand how the lowest class in a caste is mistreated.

The Mistreatment of the Lowest Caste

One aspect of the American, Indian, and Nazi German caste systems is the rampant mistreatment of the lowest castes. Wilkerson argues that this mistreatment often manifests in two ways: the division of labor and widespread terror and violence.

Division of Labor

The building of a society requires labor; according to the author, in a caste structure, the division of labor determines who will build the foundation and who will use that foundation to thrive. The menial tasks required to lay the foundation for progress are given to the subordinate caste, solidifying their place as the backs on which everyone else steps. This is true in both India and the United States.

(Shortform note: The author doesn’t go into detail about how this tenet applied in Nazi Germany. The Nazis established forced labor camps where Jews and other prisoners worked for no pay under inhumane conditions. This served two purposes for the Nazi regime: It created a constant supply of laborers to do the nation’s most backbreaking jobs, and it was a tool of the “Final Solution” because prisoners were often literally worked to death.)

The author describes how, for most of American history, Black people were relegated to the lowest-regarded and most backbreaking labor positions. Even when the country became more progressive, the dominant caste found ways to control the professional ranks of the subordinate caste. According to Wilkerson, by the mid-20th century, more Blacks became educated and worked in highly skilled occupations. But they couldn’t rise above a member of the dominant caste. Top-level executive positions were out of the question because a Black person couldn’t be a white person’s superior.

(Shortform note: Wilkerson doesn’t mention it here, but we can infer that this caste tenet in particular explains the violent backlash to the election of Barack Obama: a Black man who some white people may have believed to have “risen above his station”. We’ll discuss Obama’s rise to power and the subsequent backlash more in Chapter 9.)

The Rise of Black Talent

One area where the racial division of labor is especially prominent is the entertainment industry. According to Wilkerson, the presence of subordinate caste members in the entertainment industry started during the era of slavery. She describes how slave owners demonstrated their dominance by forcing slaves to merrily entertain them and their guests (a humiliating prospect considering their lot in life). They arguably felt entitled to their slaves’ performance. According to Wilkerson, this early need to entertain helped develop a tradition of performing in the subordinate community, which translated over generations into a prowess for the arts and athletics. Wilkerson argues that these roles are not threatening because the performers are pleasing the dominant caste, and the dominant caste still controls the related industries.

(Shortform note: This is still largely true today—the dominant caste occupies most leadership roles in the sports and entertainment industries. For example, while people of color make up 43% to 81% of the three largest professional sports leagues in the U.S., there were still only six team owners of color (including just one Black person—Michael Jordan). The same is true in the arts: One study found that 93% of film studio senior executives are white; and while the number of Black music executives has increased recently, industry insiders are skeptical whether this represents lasting change or a passing trend.)

| Dominant Caste Audiences Feel Entitled to Subordinate Caste Performance While Wilkerson discusses white entitlement to performance in the context of slavery, this trend arguably continues today: Even in the 21st century, members of the dominant caste often feel entitled to be entertained by Black artists and athletes. This sense of entitlement helps to explain the intense backlash that elite athletes Naomi Osaka and Simone Biles received when they pulled out of high-level competitions in 2021 to protect their mental health. In a podcast interview, sports journalist Jemele Hill argued that, “What’s really bothering people when they are reacting so vehemently and angrily toward [Simone Biles and Naomi Osaka] is the fact that these two women have said, ‘I choose me over your entertainment, over your ability to watch me perform.’” |

The Rigidness of Hollywood

Wilkerson argues that even with the success of musicians and athletes in the early parts of the 20th century, Black actors didn’t enjoy the same success as white actors. Because film and television emulate real life, the industry relegated Black actors to roles that emphasized their subordinate status. Much of this had to do with the legacy of minstrel shows, in which dominant caste members played caricatures of subordinate people in what is known as “blackface.” The minstrel shows involved slapstick routines portraying Blacks as jolly jesters unaware of their inferior nature and suffering.

(Shortform note: While Wilkerson primarily focuses on the American South throughout Caste, including the historic South’s fondness for minstrel shows, some sources say minstrel shows were actually more popular in the North. These shows often featured the character “Jim Crow,” who ultimately gave his name to the suite of post-Reconstruction segregation laws that kept Black people relegated to the lowest caste.)

The author describes how, as a result of the minstrel shows, Black actors only received roles as silly, ignorant, and melodramatically loyal servants. For example, Hattie McDaniel became the first Black actor to win an Academy Award for her role as the plump and devoted maid in “Gone With the Wind.” In the film, her character was so fiercely loyal to her owner, Scarlett O’Hara, that she turned against her own caste. (Shortform note: It’s worth noting that “O’Hara” is an Irish surname, and the protagonist of “Gone With the Wind” is canonically Irish. This shows that people of Irish descent were firmly considered “white” by the 1930s (when both the book and movie were released), despite Irish immigrants having uncertain racial status in the previous century.)

According to Wilkerson, the dominant caste found these roles acceptable and comforting despite being historically inaccurate. Black slaves were anything but plump considering the rations they were forced to live on, and few would have been tasked to work in their owners’ homes instead of in the fields. But the image of fat and happy slaves belied the ugliness of that dark period. (Shortform note: For this reason, Black activists have consistently protested “Gone With the Wind.” When the film was first released, activists outside one theater held signs proclaiming, “You’d be sweet too under a whip!” and “‘Gone With the Wind’ HANGS the free Negro!”)

| “Gone With the Wind” and America’s Attitude Toward Black Actors “Gone With the Wind” is a clear example of the dominant caste’s contradictory attitude toward Black entertainers. For example, while McDaniel won an Oscar for her performance as “Mammy,” she was barred from attending the Atlanta premiere of the movie. A studio employee clarified that, while Southerners wouldn’t mind seeing McDaniel join the film’s other stars on stage before the premiere, she wouldn’t be welcome to sit in the audience during the showing or use the all-white theater’s restrooms or dressing rooms. In other words, the dominant caste saw Black actors as tools for their own entertainment, not as fellow human beings. |

The Lasting Effects

As time has passed, the dominant caste has eased restrictions just enough to serve their needs in some way while still maintaining supremacy. Although successful subordinate caste members today have been able to achieve fame and wealth, thereby raising their class status, the cap on how high they’re allowed to rise is still in place because of the original occupational narrative. (Shortform note: This is especially true in business. By July 2021, only three of the Fortune 500 companies had Black CEOs. The same is true in politics, despite efforts to increase diversity: In 2021, there were just three Black senators and zero Black governors. However, there is some reason to hope. The House of Representatives is now 13% Black, which accurately reflects the demographics of the general American population.)

Terror and Violence

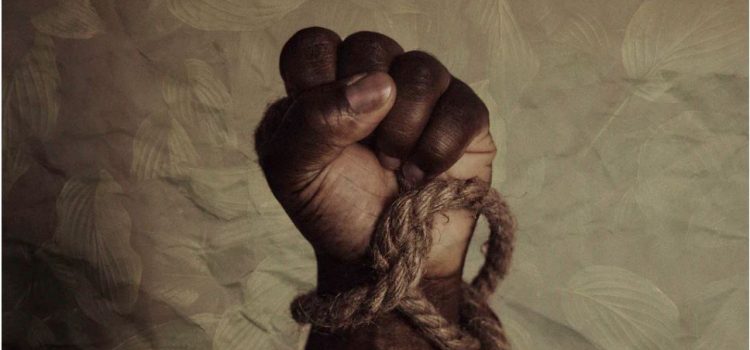

In addition to relegating them to the lowest jobs, Wilkerson argues that physical violence and psychological terror are two strategies dominant castes use to keep the subordinate caste in line. With both behaviors, the dominant caste reminds the subordinate caste of their place in society and their power over them.

(Shortform note: The science of trauma supports Wilkerson’s point here. In The Body Keeps the Score, psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk describes how trauma (such as enduring constant violence and terror from the upper caste) creates a sense of learned helplessness. In other words, in the face of unrelenting violence, members of the lower caste may feel too trapped and hopeless to fight back.)

According to the author, both the Nazis and Americans relied heavily on violence and terror to dominate their subordinate castes. Whippings and hangings were common in both Nazi Germany and the American South. These punishments were often for minor infractions or in response to seeming insolence by a subordinate caste member.

(Shortform note: Wilkerson doesn’t describe how this tenet applies to the Indian caste system. According to a 1999 Human Rights Watch report, members of the Dalit caste are often the target of violence. This is especially true for Dalit women—according to official sources, 10 Dalit women experienced sexual assault for every day of 2019.)

Physical Violence and Psychological Torture

People in the American dominant caste lynched, hung, sexually assaulted, and burned at the stake subordinate members from the moment they brought them to the new world and well into the 20th century. According to Wilkerson, these actions were unlawful when the victim was from the dominant caste, but there were no restrictions on the level of violence directed toward the subordinate caste.

(Shortform note: While there were some laws designed to protect Black Americans from violence, these laws were often ignored in practice. For example, in most states, it was technically illegal for an enslaver to kill a slave. However, in practice, enslavers were almost never prosecuted for killing an enslaved person—in the century leading up to the Civil War, the states of Virginia, South Carolina, and Texas each only executed one slaveholder for the crime of killing a slave.)

As Wilkerson describes, the dominant caste also kept subordinates in a consistent state of psychological terror to further diminish their spirit. According to the author, dominant castes in both America and Nazi Germany took this subjugation further by uplifting one member of the subordinate caste to a power position. In the concentration camps, the kapo was the head prisoner in charge of the other Jews in their cell block. On the plantation, the head slave was called the slave driver. Both positions were given enough power to discipline the other prisoners if necessary, which created dissension among the subordinate castes.

(Shortform note: While upper caste enforcers often used this practice to sow division and turn lower caste prisoners against one another, Wilkerson doesn’t mention how their strategy sometimes backfired. For example, in Liebe Mutti, concentration camp survivor Jerzy Pindera describes how the head prisoners in his camp also led the underground resistance effort. They used their special privileges to ensure that food and medicine were distributed fairly among the inmates while working to undermine the Nazis at every opportunity.)

The Lasting Effects

Wilkerson believes violence and terror reminded the enslaved of how little power they had over their bodies and warned others to stay in line. But when slavery was abolished, the investment the dominant caste had in those black bodies disappeared, and the nature of the violence and terror changed.

The favored action against blacks after Reconstruction changed from whippings to lynchings, often from highly visible trees that townspeople passed by every day. The author describes how, until the 1950s, there was a lynching in America every three or four days. The time of physical imprisonment was over, but the psychological imprisonment continued, as Black people had to live with the terrifying knowledge that they could be murdered at any time at the slightest whim of a white person.

(Shortform: Lynching was such an impactful trend in American history that in 2018, the Equal Justice Initiative created a stirring memorial to the victims. The National Memorial for Peace and Justice features one column for every county where a lynching took place, with the names of the victims inscribed on the column. The columns are suspended from the ceiling; as visitors progress through the memorial, the floor slopes downward, so that the columns eventually appear to be dangling above visitors’ heads just as the bodies of lynching victims would have. The sheer number of columns illustrates what a present threat lynching was and gives insight into the constant terror it inspired in Black communities.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Isabel Wilkerson's "Caste" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Caste summary :

- How a racial caste system exists in America today

- How caste systems around the world are detrimental to everyone

- How the infrastructure of the racial hierarchy can be traced back hundreds of years