This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat" by Oliver Sacks. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Who was Christina in The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat? Why did Christina suddenly lose control of her own body?

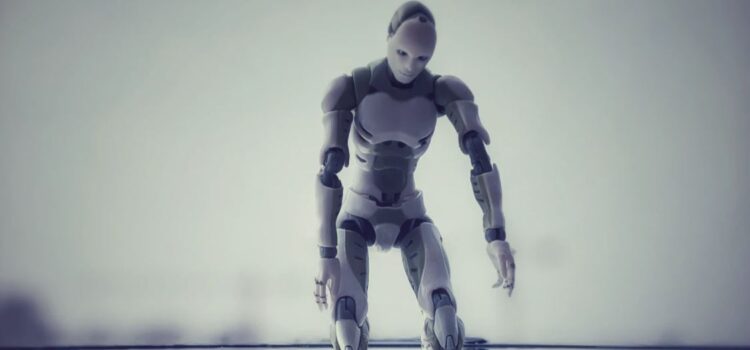

One of Oliver Sack’s patients was Christina, a young woman who suddenly became disembodied due to unknown reasons. At the age of 27, Christina suffered a loss of proprioception, meaning she was basically a brain operating a robot body.

Continue reading to learn all about Christina’s extraordinary case.

Christina’s Loss of Proprioception

So far, we’ve talked about neurological losses as they relate to “internal” functions like visual recognition and memory. But the physical body is, of course, also an essential part of the self. Control and awareness of one’s body are crucial to our sense of autonomy. They are so automatic that we scarcely think about them.

But what happens when we are no longer guaranteed the certainty of our physical selves? This brings us to the unusual and disturbing case of Christina and her loss of proprioception.

A Disembodied Person

Christina was a healthy, 27-year-old woman and mother of two. The night before she was scheduled to have a routine surgery to remove gallstones, Christina had an awful nightmare in which she imagined she had no control over her body. She wasn’t paralyzed in this dream—she could still move, but she had no control over her movement or awareness of where her body was in relation to the physical world.

Although the nightmare was initially dismissed by the hospital psychiatrist as standard pre-surgery hysteria, it soon became Christina’s living reality. She came back to the hospital, claiming that she felt weirdly disembodied, disconnected from her physical self. She had lost any sense of balance; could not hold objects or reach for them; could not stand without looking at her feet; and had suffered a total loss of tone and muscle posture, with her hands wandering freely unless she made a conscious effort to hold them in place.

Loss of Proprioception

When Sacks was called in to examine her, he found that Christina wasn’t suffering from hysteria at all. From head to toe, she had a complete loss of proprioception—her sense of self-movement and body position. Proprioception is a sixth sense, the “eyes” of the body by which we orient and position ourselves in relation to the physical world. It is how we know where our bodies are in space.

For example, even if you close your eyes, you can still touch your finger to your nose, because proprioception tells you where parts of your body are in relation to one another—you don’t need to rely on your sense of sight to tell you where your finger or your nose is.

Without proprioception, we are disembodied, with no innate awareness of our physical selves. Christina found that she could not sense her own body anymore. Whereas she once intuitively knew where her arm was, she now had to rely on her sense of vision to locate it—painstakingly using her eyes to consciously will her body to do what it had once done automatically. Whereas she once knew how to modulate her voice because her sense of proprioception gave her an awareness of her vocal cords, she now had to use her powers of hearing to regulate its volume and tone.

Christina had become a third-party operator of her body, as though it was an object that was no longer part of herself. With great concentration, she could control it, but it was no longer “hers” in any way. She was driven to the deepest despair by her condition, likening it to a “dead veil” that had enveloped her being, telling Sacks, “I feel my body is blind and deaf to itself.”

Reality Becomes Artifice

But Christina managed to regain some mastery over her body, through making extraordinary efforts and compensating for her loss with her other five senses. She regained her balance by maintaining an overly formal and upright sitting pose. Likewise, she learned to modulate her voice by adopting a theatrical, stagy voice. She had to adopt a constant pose of artifice and performance to make up for the lost reality of her proprioception.

Eventually, these mechanisms became second nature to Christina. Life was possible once again—although it would always be disembodied, and never normal.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Oliver Sacks's "The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat summary :

- Neurologist Oliver Sacks' case studies on patients with neurological impairments

- The remarkable complexity of the human brain and its extraordinary capacity to adapt

- How Sacks' work with his patients shows the pitfalls of traditional thinking about neurological disorders