This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Shallows" by Nicholas Carr. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

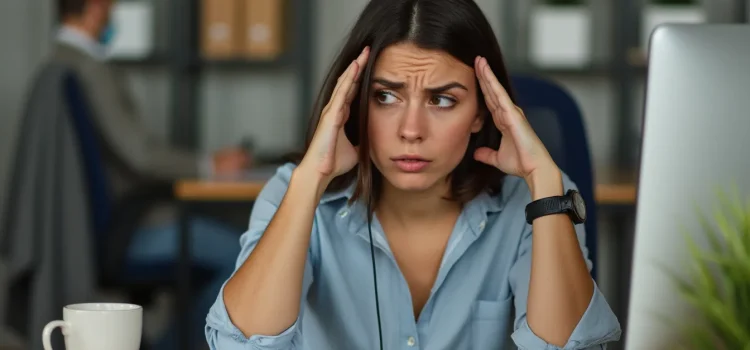

Is your attention span shorter than it used to be? Have you noticed a change in how you read and process information?

The internet has revolutionized our access to knowledge, but it may come at a cost. Nicholas Carr explores how our constant online interactions might be reshaping our cognitive abilities. He delves into the impact of digital media on our reading habits and thought processes.

Continue reading to get Carr’s insights on the loss of concentration in the digital age.

Loss of Concentration

Carr states that the internet, while a powerful knowledge tool, is eroding our capacity for sustained concentration and deep thought. Extensive internet use changes how we absorb information—instead of spending the time to understand comprehensive narratives and well-reasoned arguments, internet users pick and choose among millions of fragmented bits of data. The very design of online information encourages reading in short bursts rather than engaging with lengthy passages. Consequently, constant use of online resources may lead you to struggle with focusing on more extended texts such as books and in-depth articles on a topic.

(Shortform note: The loss of concentration that Carr describes might not be limited to individual information consumers. In Stolen Focus, Johann Hari writes that information technology can harm society as a whole. Today, we’re constantly bombarded with personalized content designed to grip our attention. Much of it is targeted at us via algorithms that exploit our evolutionary survival instinct to focus on whatever scares us the most. Spread across millions of internet users, these algorithms perpetuate a cycle of fear and anger that creates a false impression of widespread public rage. At the same time, the spread of misinformation across social media fuels animosity and mistrust, halting productive dialogue and stopping us from solving problems as a society.)

Carr also writes that the rise of electronic texts and e-books adds another layer to how we consume written content due to the hyperlinks and interactive elements that are often embedded in these formats—features that introduce the internet’s infinite distractions into a long-form document. Digital text allows for easy navigation through a document without requiring a reader to absorb its entirety, which encourages readers to cherry-pick what interests them without giving attention to the document’s context or overall arguments—essentially reducing textual works into bite-sized chunks for easy consumption.

(Shortform note: The shift to condensing information into the smallest consumable units began long before the internet. In Amusing Ourselves to Death, Neil Postman argues that it actually started in the early 1800s with the telegraph, which communicated short bursts of information not unlike the disjointed writing style that’s optimal for modern social media. Soon after the telegraph came the invention of film photography, which also delivers information in a quick, easily digestible format. Postman writes that for the last 200 years, the world has been evolving from the slow, print-centered culture which Carr holds up as an intellectual ideal to one that values information’s speed and quantity over the depth of long-form reading.)

The internet is even rewiring how our brains process information. The design of websites and other online tools encourages repeated behaviors, such as clicking links, which are coupled with audiovisual cues such as pictures, music, and videos. In essence, Carr suggests that the internet conditions us to crave quick gratification through rapid stimulus-and-reward cycles. Social media platforms further exploit this reward cycle by leveraging our innate desire for social approval—for instance, by counting how many “likes” we get when we repost attention-grabbing headlines. Internet use brings some benefits, such as enhanced hand-eye coordination, but the cost seems significant—a diminished ability for focused thought that stifles human creativity.

(Shortform note: The neurochemical driver of the process Carr describes is dopamine, which is often characterized as the brain’s “pleasure chemical.” In Dopamine Detox, Thibaut Meurisse says that social media platforms hijack your body’s dopamine response as a tool to steal your attention. Receiving likes, comments, and social validation activates the brain’s reward centers, reinforcing your desire to seek out more. This cycle not only becomes addictive, but it also leads to sensory overload, which prevents you from focusing on what matters most. Meurisse writes that when you’re constantly looking for the next jolt of dopamine online, you’re easily bored by low-stimulation activities such as creative projects or deep, focused reading.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Nicholas Carr's "The Shallows" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Shallows summary:

- The ways internet use is literally reconfiguring our brains

- How information technologies reshape human behavior

- The sweeping societal consequences of these changes in human cognition