This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "The Hero with a Thousand Faces" by Joseph Campbell. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What is the King Midas story about? How does it conform to the conventions of Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey?

The King Midas story is about what happens when we’re greedy and don’t think things through. The phrase “Midas touch” comes from this story, and while the phrase refers to someone who has good luck, in the King Midas story, the king’s luck runs out.

We’ll cover the King Midas story and how it fits into the traditional hero’s journey template.

The King Midas Story

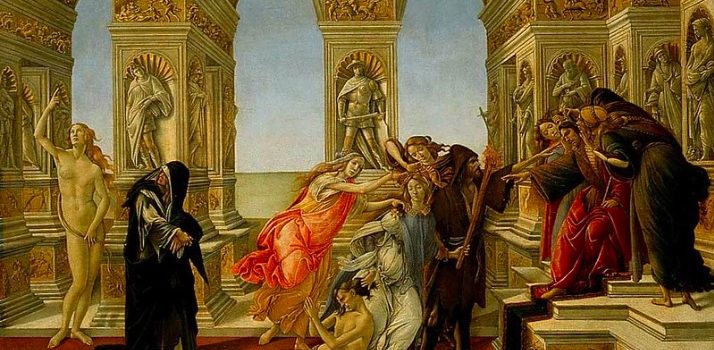

The Greek King Midas story is a neat illustration of the woe that accrues to the hero who seeks mere worldly possessions or wealth from the gods. Midas of Greek mythology wins from the god Bacchus the right to request anything he desires. Foolishly, Midas wishes to have everything he touches turn to gold. Bacchus grants this wish, and, sure enough, every twig, apple, and stone Midas touches becomes golden. He orders a magnificent banquet to celebrate what he believes is this glorious bounty, only to realize his folly. When he touches the meat, it becomes inedible gold, as does the wine in his chalice. When his beloved daughter comes to comfort him, she too is transformed into a lifeless golden statue.

The King Midas Story and the “Ultimate Boon” Stage

What does the King Midas story of Greek mythology have to do with Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey? The King Midas story is relevant to Stage 11 of the hero’s journey: The Ultimate Boon.

In this stage of the hero’s journey, the hero achieves their goal and is reborn as a superior being. This is what happens in the King Midas story when Midas wins his desire from Bacchus. This stage is often shown by the ease with which the hero is now able to obtain the things that they seek. In the Irish legend of the Prince of the Lonesome Island, the hero is rewarded by being able to eat from a table with food that automatically replenishes, freeing him from hunger and want—he has achieved limitless bounty, indestructible life, the Ultimate Boon.

Many folk traditions, like the King Midas story, explore this concept of indestructibility through the motif of the spiritual double or doppelganger. This is an external soul of the individual, another part of the self, that exists free from the injuries that the physical body endures. Only by destroying that soul (sometimes represented as a literal object like an egg) can the individual truly be extinguished. Among some Australian aboriginal people, a young man being initiated to the tribe is taken to a cave and shown a slab of wood with carvings on it. He is informed that this object is, in fact, his body and that he should never remove it lest he experience agonizing pain.

The Folly of Material Wealth

If the King Midas story of Greek mythology falls within the traditions of the hero’s journey, why isn’t there a happy ending?

The search for physical immortality or material wealth, instead of spiritual enlightenment, will always end in failure for the hero, for it is to confuse the meaning of what the hero’s journey is supposed to be all about. As the Japanese proverb says, “The gods only laugh when men pray to them for wealth.” This is a common error among heroes, as in the King Midas story.

Still, this desire for earthly glory has led humans to undertake extraordinary journeys: famously, the Spanish explorer Ponce de Leon accidentally discovered Florida in the course of pursuing the fabled Fountain of Youth. Sometimes the hero starts out seeking something tangible—weapons to slay his enemies, eternal life, material wealth—but through the struggle of the adventure wins an infinitely greater prize: self-actualization and enlightenment.

Example: Gilgamesh

Let’s look at another example, like the King Midas story, of a king who desires too much.

In the ancient Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh (the world’s oldest surviving work of literature), the legendary king Gilgamesh seeks immortality in the form of the plant “Never Grow Old.” He comes to a cave by the sea, where he meets a manifestation of the goddess Ishtar. She urges Gilgamesh to turn back from his quest for immortality and instead accept the pleasures of mortal life, to “Regard the little one who takes thy hand, let thy wife be happy against thy bosom.” But he insists and she guides him to the ferryman Ursanapi (a supernatural helper) who will convey him across the waters of death to the land where Utnapishtim lives (Utnapishtim is the sole survivor of the great flood from the Babylonian creation story and the Babylonian precursor to the better-known Biblical figure of Noah).

Utnapishtim tells Noah that the plant he seeks grows at the bottom of the sea. Gilgamesh thus ties stones to his feet and goes into the sea to descend to the ocean floor. He finds the plant and plucks it from the seabed, though it cuts and mutilates his hand. When he returns to shore, Gilgamesh rests, but the plant is stolen from him by a serpent who instead consumes it and thereby gains the power to shed its skin—thus achieving perpetual youth. Gilgamesh breaks down and weeps at his misfortune.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "The Hero with a Thousand Faces" at Shortform . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Hero with a Thousand Faces summary :

- How the Hero's Journey reappears hundreds of times in different cultures and ages

- How we attach our psychology to heroes, and how they help embolden us in our lives

- Why stories and mythology are so important, even in today's world