This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Psychology of Money" by Morgan Housel. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Have you ever made an investment that didn’t turn out the way you expected? What should you do if your investment fails?

It’s easy to become discouraged when things don’t go as planned, especially when your money is on the line. However, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t take risks. Investment failures do occur, fairly frequently, but if you keep trying, you could get lucky enough with one investment that it outweighs any failures.

Here is why you shouldn’t let failure hold you back from trying again.

Even if You Fail Frequently, You Can Still Succeed

Failure is fairly common in the world of investing. Yet, even if you fail frequently, you can still succeed. Investment failures should not discourage you from trying again:

Housel explains that nearly every successful financial venture you hear about owes its success to low-probability outlier events—luck. These events, when positive, compensate for a larger number of smaller setbacks that a company might go through. For example, the successful companies that drive investment returns are all outliers. As Housel notes, the assets of the Russell 3000 Index, which invests in public companies, increased by nearly 75 times over 34 years. But 40% of the index’s companies lost most of their value. The gain was driven by just 7% of the index’s companies—the outlier events—which were successful enough to offset the 40% that failed.

| The Role of Luck in Successful Companies The Russel 3000 index represents the United States’ 3000 largest companies, serves as the basis of many financial products, and strives to be the “benchmark of the entire U.S. stock market, indicating that the companies included in the index are all fairly successful. This fact supports Housel’s theory that it’s luck that separates the most successful of these from the rest, as we can assume that all of them are at least somewhat regularly making smart business decisions, and yet it’s only 7% that break away from the pack with outstanding results. This calls into question Housel’s earlier advice to watch for patterns—if 40% of a group as competent as the companies in the Russell Index fail, it’s difficult to know which patterns of behavior to emulate and which to dismiss. This is why even business books, which try to collect and share these patterns, don’t always get it right. Sixteen of the 50 companies highlighted in three business classics failed within a few years of the books’ publications, and only five continued to impress years later. |

Similarly, outlier events drive the success of individual companies. For example, Nintendo failed repeatedly to break into the American video game market until the massive success of Super Mario Bros.

Crucially, outlier events are powerful enough that they offset the failures: It didn’t matter that Nintendo’s other products failed because Super Mario Bros. did so well that it accounted for the losses.

(Shortform note: In this chapter, Housel only discusses the positive impact that outlier events have. However, the opposite is also technically true: a negative outlier event could drive the failure of an otherwise successful company because it was so powerful that it offset all of the other successes.)

Since we only pay attention to these outlier events—and not to the failures that the outlier events offset—we forget how rare outlier events are (one in a million, in many cases) and conversely just how common failure is. As such, we overreact when failures inevitably happen to our own ventures. But when you realize how common failure is, you realize that you can fail most of the time and still be successful—and thus, you can react to your failures appropriately.

(Shortform note: While, as Housel notes, we rarely pay attention to the failed products or companies that the outliers offset, we do pay attention to these failures in the context of individuals’ careers: We often talk about how often the successful people failed before achieving their (outlier) success. Reminding yourself of stories like these—like the fact that Richard Branson founded 400 companies before moneymaker Virgin Galactic—may help you remain calm next time you fail.)

How to React to Investment Failure

What, exactly, counts as an appropriate reaction to investment failure?

First, Housel recommends, pay attention not to the extent or frequency of individual failures but to the impact of your financial failures on your overall financial health. Housel argues that the world’s most successful people probably fail just as frequently as you do. But we judge their success by the overall impact their outlier events—the tiny percentage of actions that led to their success—had. Similarly, the outlier events in your life can offset the impact of many individual failures. Therefore, paying too much attention to how often you fail or the outcome of an individual investment paints an inaccurate picture of your financial health. Instead, pay attention to your overall financial health, since that’s what matters.

(Shortform note: To avoid focusing on the negative impact of failure, experts recommend that you reframe your view of failure, seeing each failure as an opportunity to learn what not to do in the future.)

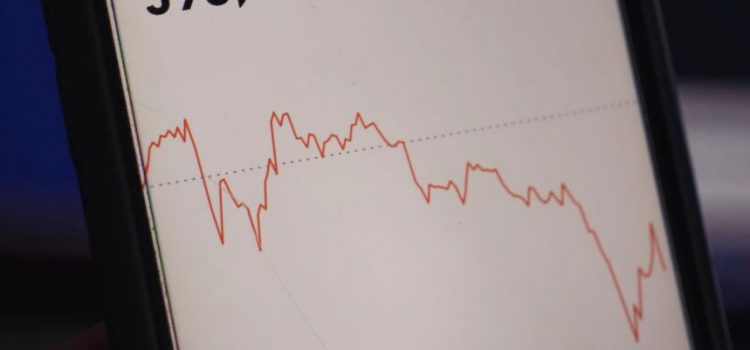

Second, Housel recommends, remain calm when others panic. Housel implies that people panic and pull their investments out when the market fluctuates because they’re trying to time the market—to avoid the market when it goes down and jump back in when it rises. But this is impossible: Nobody can successfully time the market. Instead, Housel recommends, accept that it’s OK to lose money sometimes because individual failures probably won’t matter in the long run. Once you do, you’ll be able to leave your investments alone even when the market fluctuates—and since they’ll be in the market longer, they’ll compound more and make more money.

(Shortform note: If you’re tempted to pull your investments out of the market when it fluctuates, remember this statistic from I Will Teach You To Be Rich: On average, the stock market’s annual net return is about 8% (after accounting for inflation). That number is an average from decades worth of data, which means that your money will earn an average of 8% per year over the long term, even if that rate fluctuates in the short term. So no matter how badly things go, you’ll still probably average about 8% gain in the long run.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Morgan Housel's "The Psychology of Money" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Psychology of Money summary :

- Why the key to financial success lies in understanding human behavior

- How to make better financial decisions

- How chance plays a bigger role in our financial lives than we think