This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Ways of Seeing" by John Berger. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What factors are at play when we’re interpreting art? Why do different people see art in different ways?

Images are inherently subjective—our experiences and beliefs influence what we see. When we look at visual art, we often place ourselves within images, which influences how we interpret their meaning.

Keep reading to learn more about the factors that influence the way we interpret art.

What Is an Image?

Foundational to art analysis is the concept of what an image is. Berger makes a clear distinction between a sight and an image.

An object, living being, or landscape that exists before your eyes in real life is a sight. The couch you are about to sit on, the floor beneath your feet, and the flowers you see in the garden outside your window—these are all sights.

An image is a sight that has been reproduced or recreated. The sight becomes an image when it is separated from the place and time in which it truly exists (or existed). A painting, a video, even a photograph—these are images.

Berger says that once a sight becomes an image, it’s no longer an exact record of what was. The act of reproducing a sight inherently adds a subjective value to the image. Rather than being a historical record of the sight, it’s now a record of how someone saw the sight…and how you are seeing the image now.

(Shortform note: When an image is continuously reproduced, you might imagine the meaning being skewed each time—similar to the childhood game of Telephone. With each iteration, a nuance is added or a distortion takes place.)

Images Are Subjective

Images are inherently subjective—a human reproduced the sight (creating an image), another human is viewing the image, and no human can be completely objective. Berger explains that, even with a photograph, which is generally considered a more accurate reproduction than a painting, the photographer makes dozens of conscious and subconscious decisions that affect the message conveyed (lighting, positioning, filters, focus), and the viewer is interpreting art based on a lifetime of experiences that inform his perspective.

(Shortform note: The fact that seeing is subjective is beneficial to the industry of art itself. The phrase “It’s an art, not a science” is a direct reflection of the subjective nature of art.)

Our Experiences and Beliefs Influence What We See

Berger argues that our beliefs, experiences, and knowledge strongly influence what we see.

Imagine three people are looking at the same image of an iceberg. The person who is concerned with climate change will instantly assign a symbolic meaning and see a melting iceberg within a rapidly heating planet. The person who has been to Alaska will see a landscape that is familiar and majestic. The third person, a history buff, will see what caused the sinking of the Titanic. In each case, the belief, experience, or knowledge influences what the person sees.

(Shortform note: One study found that the amount of context we receive influences how we interpret visual information. Particularly, when there is little to no context, we tend to fill in the blanks ourselves and think more critically. When given context, our brains naturally move toward it (also known as confirmation bias) and we’re less likely to diverge from the information given. This supports Berger’s argument that what we believe influences what we see.)

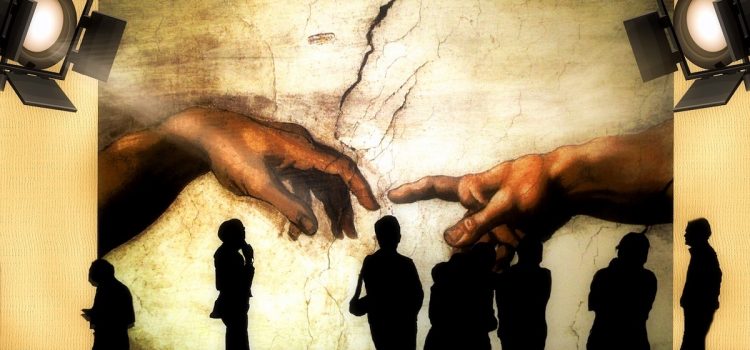

To See Is to Place Yourself Within the Image

Berger argues that, when you see an image, you place yourself within it. If you look at an advertisement for a Hawaiian resort, for example, you’ll imagine what it would feel like to be there. You generate ideas about how it would feel, smell, look, and so on, based on your beliefs, experiences, and knowledge. This act of inserting yourself into the image can happen in the blink of an eye and without your consent. It’s the reason we wince when we see a movie character break a bone—we don’t always want to place ourselves in the image, but we do it anyway.

Berger warns that, if we’re manipulated into believing an image has a certain meaning, we place ourselves into that meaning. And if the meaning is obscured (mystified) altogether, then we’re deprived of the history that may benefit us in our present. He argues that the elite have been doing this to the working class since the Renaissance, and in later chapters, we’ll take a look at the examples he uses to illustrate this argument.

(Shortform note: Placing yourself within the image doesn’t necessarily mean that you agree with the message that’s being communicated. A famous quote from F. Scott Fitzgerald tells us that “The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time,” Perhaps Berger doesn’t give the public enough credit to believe they can experience the image without becoming swept away by its belief system.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of John Berger's "Ways of Seeing" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Ways of Seeing summary :

- Why we don't need experts to "translate" works of art for us

- How the dominant class uses art and art criticism to “mystify” the working class

- How our experiences and beliefs influence what we see