This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "A People's History of the United States" by Howard Zinn. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Why did the US carry out a policy of Indian removal? What was the impact? Who benefited?

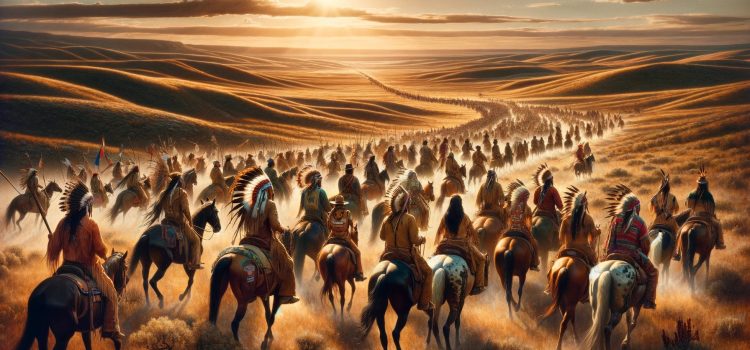

The US made its largest territorial gains during the first half of the 19th century as the frontier pushed west. Historian Howard Zinn discusses one of the conflicts that arose from this massive rate of expansion: Indian removal.

Read more to learn about this policy and its legacy.

What Was the Indian Removal?

During its westward expansion, the US conducted a policy of Indian removal, or the displacement and ethnic cleansing of American Indian tribes. The US carried out Indian removal through violence, exploitative treaties, and encouraging tribes to turn against one another to weaken resistance. Unlike during the colonial era, the main beneficiaries of Indian removal during the US’s expansion weren’t poor white frontiersmen. Instead, wealthy land speculators or railroad companies collaborated with the government, buying land that the US forced Indians off of. Then, they profited by developing the land, renting it out to poor farmers, or selling it for a higher price.

(Shortform note: In addition to purchasing land within the US itself, many American railroad companies and speculators bought land throughout Central America during the mid-to late 19th century. While these purchases weren’t as directly connected to ethnic cleansing, they did allow US elites to gain influence over and exploit foreign nations. Examples include US construction of the 1855 Panama railroad and American company United Fruit getting its start in part by purchasing land and building railroads in Costa Rica in the 1870s. Increased US stakes in the region also motivated several of America’s early imperial projects.)

Indian removal policies were devastating economically, physically, and spiritually to Indian tribes. Many had lived off of their land for generations, accumulating knowledge of the area as well as cultural and religious ties to it. Once displaced, they often had to change their way of life—going from a hunting-based lifestyle to an agricultural lifestyle, for example—in an unfamiliar region. Many tribes resisted Indian removal in a number of ways, through violence, attempts to assimilate and integrate into American culture and life, or even legal means. While some of these attempts were met with limited or temporary success, none were able to stop or even significantly slow the process of Indian removal.

For example, in the Supreme Court case Worcester v. Georgia, the Cherokee Indian tribe fought to hold onto their land in Georgia. Although they won the case and the right to stay, President Andrew Jackson and the Georgia state government ignored the ruling. Not long after, the US government ethnically cleansed the Cherokee tribe, forcing them to march along the “trail of tears” to Oklahoma. Thousands died on the journey from cold, starvation, and disease.

(Shortform note: While more liberal-minded American politicians often voiced displeasure with the harsh treatment of American Indians, they rarely acted to stop it—and sometimes even supported it. For example, President Thomas Jefferson wrote that white men and American Indians were equal and discussed his policies toward them in terms of a benevolent mission to “civilize” and assimilate them. In practice, though, his policies formed the basis of what would eventually become Indian removal—providing a formal system to force or coerce American Indians into giving up and leaving their land. This gap between the rhetoric and action of elites shows why Indian removal proceeded despite common vocal dissent.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Howard Zinn's "A People's History of the United States" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full A People's History of the United States summary:

- A bottom-up view of American history focusing on the people, not the politicians

- How Indigenous people, Black Americans, women, laborers, and activists lived

- Why social movements of the 60s and 70s failed to create lasting change