This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "What Every Body Is Saying" by Joe Navarro and Marvin Karlins. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

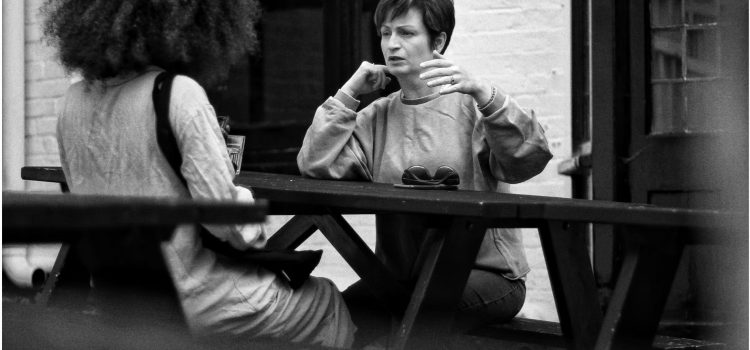

Do you want to learn how to read people’s body language? What can you learn about a person based on their body language alone?

Body language cues can tell you more about a person than their words, provided that you know how to decode them. According to former FBI agent Joe Navarro, there are five key steps you need to follow when trying to size someone up based on their body language.

Here’s how to read body language, according to Navarro.

Step 1: Observe

In his book What Every Body Is Saying, former FBI agent Joe Navarro explains how to read people’s body language. The first step, he says, is to learn to observe people. Research has proven that people aren’t typically aware of their surroundings and that most of us fail to notice obvious things in our visual environment, such as other people’s clothing or the color of the building we’re in.

(Shortform note: Being a good observer isn’t easy. According to psychologists, most of us suffer from inattentional blindness, or the failure to notice things in the world around us. This phenomenon has been famously illustrated by the Invisible Gorilla experiment conducted at Harvard University, which had participants pass a basketball and keep track of the number of passes. However, during the experiment, a person in a gorilla suit passed through the scene and was noticed by only half of the participants.)

To be a good observer, then, practice becoming situationally aware. This means keeping constant tabs on where you are and what’s going on around you. When you practice situational awareness, you’ll naturally notice more in your surroundings, which will aid you in picking up body language cues. However, Navarro cautions you to observe discreetly so that your behavior won’t affect how others act.

(Shortform note: The term situational awareness was originally used in a military context, defined during World War I as a necessary skill for pilots to safely and effectively handle their aircrafts. Since then, it’s taken on multiple definitions but centers on the idea of being aware of the past and the present of a situation so that you can predict potential outcomes. One model identifies three levels of situational awareness: perceiving your environment, understanding the current situation, and anticipating the future situation.)

Step 2: Identify Baseline Behaviors

When you observe a person’s body language, Navarro says you must first make a mental record of a person’s behaviors at the start of your interaction. This allows you to get a baseline to measure your future observations against. Take into account their overall physical appearance, hygiene, and behavior—such as whether they’re loose, relaxed, and well-groomed or stiff, fidgety, and unkempt.

(Shortform note: Navarro’s suggestion of identifying a baseline is an important step for measuring change and interpreting information for other purposes, such as in cancer treatments. When treating cancer, doctors measure the tumor before treatment which is then used as the baseline to gauge the treatment’s effects.)

You should establish a baseline before trying to interpret body language because people have different personalities or cultural backgrounds that can affect their behavior. For example, someone with a shy personality might naturally have more nervous or withdrawn body language compared to someone more outgoing. Alternatively, some cultures might display more intimacy than others, such as through hugs and physical touch.

(Shortform note: Beyond acknowledging cultural differences when reading body language, psychologists point out two other factors you should consider: developmental and psychological differences. People with developmental disorders, such as individuals on the autism spectrum, display and perceive nonverbal cues in different ways. Similarly, mental health conditions, such as anxiety, can also influence a person’s body language.)

When analyzing someone’s starting behavior, assess it in the context of the situation they’re in. Consider things such as their surroundings and what they’re doing there so that you can know what behaviors to expect and what behaviors are abnormal. For example, you should expect someone at a job interview to showcase more nervous behavior than someone shopping at a grocery store.

(Shortform note: While Navarro doesn’t go into depth about how to better assess what behaviors are normal and abnormal in different contexts, in The Nonverbal Advantage, Carol Kinsey Goman offers an exercise that lets you practice assessing when behaviors are expected and when they’re abnormal. She suggests identifying one body language cue (like fidgeting) and listing the situations you can think of where this behavior would be acceptable or normal (like before a flight). Then, consider what changes would make the behavior abnormal, such as how a different location might affect the meaning of this behavior.)

Step 3: Observe From the Feet Up

While it may seem intuitive to read a person’s body language from head to toe, Navarro suggests you do the opposite: start observing from the feet up. He explains that your lower body is the most honest half. This is because the feet and legs of our ancestors played a more significant role in their survival. Back then, the lower body came into contact with dangers such as predators or sharp objects more frequently, which makes it especially sensitive and reactive to stimuli.

(Shortform note: According to Navarro, your lower body reacts more sensitively to stimuli because it was more at risk to dangers during our early human history. However, a look through our evolutionary history reveals that our ancestors didn’t always walk upright. Additionally, around three and a half million years ago, our ancestors could walk on two legs but spent the majority of their time in trees. Ultimately, there is no scientific consensus on exactly why humans became bipedal. However, over three million years of bipedalism has heightened the sensitivity of our lower bodies, enabling Navarro to identify them as the most honest half of the human body.)

Our upper body and, more specifically, our facial expressions, are less honest. Navarro explains that we learn to mask or fake our facial expressions at a young age to avoid disagreements and maintain peaceful relationships. Therefore, he advises you to start at the most honest bottom half of the body to get a more accurate impression of a person’s true emotions.

(Shortform note: Lying and masking our facial expressions requires a theory of mind, or the ability to understand that other people have different beliefs than your own. According to psychologists, children develop this ability around the age of four or five, backing Navarro’s claim that we learn to fake facial expressions at an early age. In this way, learning to deceive others is a developmental benchmark.)

Step 4: Look for Changes in Behavior

As you make your observations, be alert to any rapid or gradual changes in behavior. Navarro explains that since the limbic system automatically responds to stimuli, these behavioral changes signal shifts in emotion—for instance, from confidence to insecurity. If you notice what stimulus precedes these behavioral changes, such as a new person entering the room, you can identify not only how someone feels about the situation, but why they’re feeling that way.

(Shortform note: When noticing changes in behavior, Robert Greene warns you to avoid Othello’s error in The Laws of Human Nature. This error occurs when you incorrectly assume you know the reason behind a person’s display of emotion because of your own expectations and predispositions. This bias is named after the Shakespeare play Othello, in which Othello believes his wife cheated on him and assumes that her nervousness confirmed his belief, when in reality, she only felt intimidated.)

Step 5: Look For Multiple Behavioral Cues

Before making any assumptions about a person’s true sentiments, Navarro suggests you look for multiple behavioral cues rather than rely on a single observation (we’ll discuss what specific cues you can look for shortly). Since each person has a unique personality and their own behavioral quirks, you can get a more reliable reading by observing multiple indicators.

(Shortform note: Navarro advises you to look for multiple clues, which Carol Kinsey Goman refers to as gesture clusters—multiple behaviors that reinforce a common message. In The Nonverbal Advantage, she elaborates that single cues could mean many different things or nothing at all, which is why you can get a clearer picture by observing clusters of behaviors. Goman suggests you count to three after making an observation to stop yourself from making instinctive judgments based on a single cue. Then, look for two more cues that support your first observation.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Joe Navarro and Marvin Karlins's "What Every Body Is Saying" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full What Every Body Is Saying summary:

- A guide from a former FBI agent on how to decipher body language

- How to master the language of nonverbal communication

- How to detect when someone is lying to you and access their true thoughts