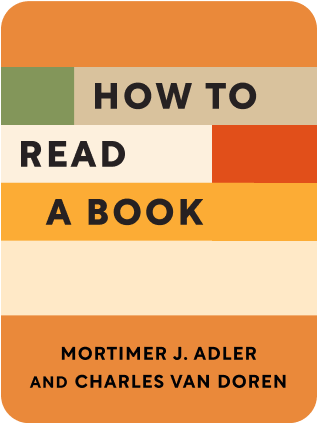

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "How to Read a Book" by Mortimer J. Adler and Charles van Doren. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

How is reading imaginative literature different than reading expository writing? What four questions should you ask about the book?

In How to Read a Book, Mortimer Adler says that reading imaginative literature such as novels, plays, and poetry should be approached differently than informational books. The main difference is that imaginative literature is trying to convey emotions and experiences.

Here’s how you can read imaginative literature like a pro.

Reading Imaginative Literature

Most of the principles in How to Read a Book apply to expository writing, where the aim is to convey information or lead to action. The goal of imaginative literature is different: to convey an experience. A work of fine art is “fine” because it is an end in itself.

Thus, as a reader you should open yourself to being emotionally affected – don’t resist the effect. Allow it to move you. Likewise, don’t criticize imaginative writing until you appreciate what the author has tried to make you experience.

Where expository writing defines its terms with explicit precision, imaginative works deal in ambiguity. Having multiple meanings enhances the richness of a set of words.

Imaginative works are judged by how well they reflect reality. Not necessarily in verisimilitude (as science fiction or fantasy violate) but rather whether what is being said rings true – characterization, how characters respond to events, whether themes are revealed that reflect your experiences.

Reading imaginative works should still be active and critical. When you say you like or dislike a fictional work, you should articulate why, and what is good or bad about the book.

Imaginative works don’t contain explicit terms, propositions and arguments, but the analogy works:

- The terms are the set pieces: the setting, the characters, and the events.

- The terms are connected in propositions: the characters live and breathe in the world.

- The arguments are the interaction between the propositions: how the characters respond to events.

The analogy breaks down on inspection, but the purpose of this reasoning is to enhance your pleasure by understanding why you like something.

The Four Questions

- What is this book about as a whole?

- Summarize the plot of the book in a few sentences.

- What is being said in detail, and how?

- What are the elements of the work – its setting, characters (and their thoughts and actions), events?

- What is the shape of the plot, to climax and aftermath?

- Is the book true, in whole or part?

- Do the characters behave realistically?

- What have you learned from the experience?

- What of it? Why is this important? What follows?

- Does it satisfy your heart and mind? Do you appreciate the beauty of the work?

Specific Advice for Types of Imaginative Literature

Stories/Novels

- Stories are universally enjoyed – the authors suspect this is because it serves our unconscious needs.

- Readers live out fantasies in the characters – passionate love, empire construction, overcoming struggle.

- People crave a feeling of order and justice. In contrast, in stories considered bad, people seem to be punished or rewarded with no rhyme or reason.

- The great books tend to satisfy the deep unconscious needs of almost everybody.

- Read it quickly with total immersion, ideally in one sitting. Don’t draw it out just to savor it, since this is indulging your unconscious feelings about it.Don’t disapprove

- Suspend your disbelief about events. Don’t disapprove of something a character does before you understand why he does it. And don’t judge the world until you’ve lived in it to the extent of your ability.

- If the book has a lot of characters, don’t worry about knowing them all. This is just like moving to a new town. The important ones will keep resurfacing.

- Once the story ends, it ends. Your imagination of what the characters do afterward is meaningless.

Plays

- Most plays are not complete when read, since they’re meant to be performed on the stage. They lack stage direction.

- Pretend that you’re directing the play. Instruct the actors on where to stand, where to face, and how to say their lines. Tell them the importance of certain lines.

- Some lines of plays are ambiguous – how you choose to act will affect the interpretation of the scene.

- eg Shakespeare’s Hamlet has a scene where Hamlet’s line “ha, ha! Are you honest?” could be construed as him knowing his father is listening to him, or not.

- When confused by a line, say it aloud and with meaning – this will clarify many a line without having to consult a dictionary.

- In tragedies (eg Aeschylus), the essence of tragedy is time, or the lack of it. There is no problem in Greek tragedy that couldn’t have been solved with more time. We see what should have been done, but would we have been able to see it in time?

Poetry

- Poetry is a spontaneous overflowing of the personality. Defining what constitutes poetry is difficult, but you know it when you see it.

- Read it through without stopping and trying too hard to understand every single line. The essence of a poem is never in the first line, but rather in the whole.

- Then read it aloud. You’ll pick up on new insights.

- Most poems are about a conflict, even if it’s not explicitly stated (eg love vs time, life and death, transience vs eternity)

- Poems often stand alone. Don’t feel you have to know about the author and the times.

- Read great poetry over a lifetime – you’ll discover new things about it.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Mortimer J. Adler and Charles van Doren's "How to Read a Book" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full How to Read a Book summary :

- How to be a better critic of what you read

- Why you should read a novel differently from a nonfiction book

- How to understand the crux of a book in just 15 minutes