This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Unlimited Memory" by Kevin Horsley. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Is your memory just plain bad? Do you have a hard time paying attention?

Your ability to commit information to memory depends on how well you pay attention to it. According to Unlimited Memory by Kevin Horsley, paying close attention to what you’re learning requires you to be present in the moment.

Check out how to pay attention and enhance your memorization skills.

Attention: Stay Present While Learning

To learn how to pay attention better, you must focus on the task at hand and block out irrelevant stimuli or interruptions. If your mind is cluttered with discouragement, distraction, or a lack of a clear goal, you can’t be present. Below we’ll explain how to manage these types of clutter to help you pay better attention.

(Shortform note: Mindfulness is a term used to describe being fully present in the moment and unbothered by external distractions. Research shows that mindfulness practices like meditation can improve memory capacity and function by reducing stress and stimulating structural changes in the brain (a phenomenon known as neuroplasticity). Pairing Horsley’s techniques with mindfulness practices may improve your memory even further.)

1. Dealing With Discouragement

According to Horsley, the way you talk to yourself determines how well you can pay attention. If you tell yourself you’re bad at paying attention, and you believe you’re bad at it, you will be. He explains that people often have limiting beliefs that keep them from improving their abilities. These beliefs include things like “I’m unintelligent,” “I don’t have enough help from others to do this,” and “It’s too hard.” Believing these things will make them true, but shedding these beliefs will unlock your potential. To get rid of your limiting beliefs, replace them with empowering beliefs like “I have a natural aptitude for learning and remembering,” and “I can do anything I set my mind to.”

(Shortform note: Because they’re often subconscious and deeply ingrained, we may not recognize our own limiting beliefs. To help you identify them, be aware of any time you think something like “This is just how I am.” As humans, we’re capable of great change, so any belief that makes you think you can’t change might be a limiting belief you need to overcome. On the other hand, sometimes you may hold a belief that you consciously know isn’t true but that still influences your behavior. Simply telling yourself that these beliefs aren’t true won’t be helpful since you’re already aware they’re not true; thus, Horsley’s advice to replace the limiting belief with an empowering one will have a greater impact than simply saying the limiting belief isn’t true.)

2. Dealing With Distraction

Another reason we struggle to pay attention and be present in the moment is that we try to do too many things at once. We often attempt to multitask when we’re learning, but Horsley explains that multitasking is impossible because you can’t direct your attention to more than one thing at a time. Research shows that multitasking slows you down and increases the number of mistakes you make. If you stop trying to multitask, you’ll find you can pay attention more closely and for longer periods than if you continue to try to split your focus. To do this, Horsley recommends training yourself to focus only on one thing at any given moment and avoid the urge to constantly distract yourself.

| When Can We “Multitask”? Experts suggest that what we tend to think of as multitasking is actually serial tasking, or switching rapidly between tasks. As Horsley asserts, serial tasking reduces efficiency and performance on whatever you’re doing because of the mental energy you expend by switching tasks. However, there are certain activities that you may be able to do simultaneously provided that 1) one of the activities is automatic enough that it doesn’t require your conscious attention, and 2) the two activities don’t require the same types of neural processing. For example, you can’t write an email and listen to a podcast at the same time because they both require language processing, but you could potentially write an email and exercise on a stationary bicycle at the same time because the bicycle doesn’t require your conscious attention or your language processing skills. However, even if two tasks can be done at the same time, one of them may still prove a distraction. Athletes training for an important event, for example, may not want to distract themselves with music or a movie: Even though the tasks engage different parts of the brain and the exercise they’re doing is something they can do automatically, distractions can keep them from focusing on their form and technique, which can impede their progress. |

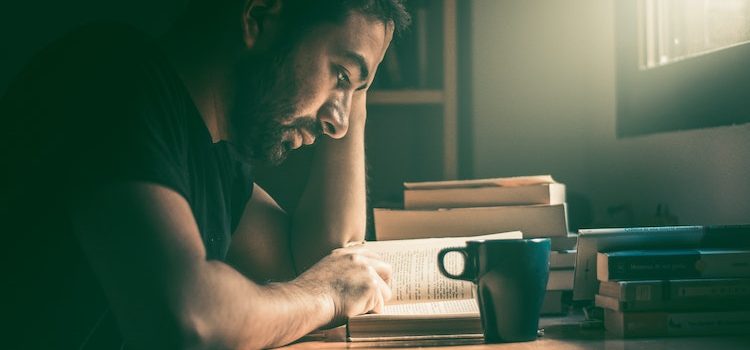

3. Creating a Clear Goal

When trying to learn something, identify two aspects of your goal: 1) what you want to learn and 2) how you want to apply it. And the more specific these goals are, the better. According to Horsley, a lack of a clear, specific goal in what you’re focusing on creates a disconnect in your mind between what you’re trying to do and what you want to do: If you don’t know what your goal is, you won’t know how to go about achieving it, and you won’t be able to tell when you have achieved it. Establishing a clear goal requires you to be curious about what you’re learning so you’ll have a better idea of how you can apply the topic to your life. This will help you establish why you’re learning this information, which makes it easier to organize your ideas and retain knowledge.

(Shortform note: In Flow, psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi affirms the importance of goals in achieving a state of flow—a state in which you feel a strong sense of purpose and direction toward achieving your goals (similar to the state of focused attention that Horsley describes). However, Csikszentmihalyi adds that having too many goals can be a distraction and keep you from achieving any of them. He also notes that you’ll need to adjust your goals as you go along to avoid becoming anxious or bored. For example, if you achieve your goal, you need a new one to motivate you to keep progressing, and if you hit a major obstacle you may need to change your current goal to accommodate this challenge.)

You also need to identify what about the topic interests you, because we naturally struggle to pay attention to anything that doesn’t interest us. If your topic isn’t immediately of interest to you, look for ways to connect it to things that do interest you.

(Shortform note: In Grit, psychologist Angela Duckworth suggests that it’s not enough to develop an interest in something; rather, you need to maintain that interest in the long term by turning that interest into a passion. If you’re passionate about what you’re learning, you’ll be able to keep up with a consistent practice instead of losing steam when your interest starts to fade.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Kevin Horsley's "Unlimited Memory" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Unlimited Memory summary:

- Why there's no such thing as a bad memory

- How anyone can train their brain to learn and remember anything

- Memory association techniques and how to use them