I’m not all that smart. I forget a lot of things. I didn’t get perfect scores on tests without trying, like some of my friends did.

But there is one thing I know how to do—read and learn. Over 20+ years of learning, I’ve figured out how to learn better and faster than most people I know.

I collected these reading tips from people smarter and more accomplished than me—like Elon Musk, Warren Buffett, and Mark Cuban (we’ll cover each of their strategies below).

And reading well makes a difference. I credit reading for most of the good things in my life—getting into Harvard for college and graduating summa cum laude (top 5%); attending the MD-PhD program at Harvard Medical School and MIT (14 acceptances each year, for a 2% acceptance rate); my success in building multiple profitable businesses.

More importantly, reading has helped me outside of work—to build a wonderful marriage, become a better friend, and just be happier.

I’m in good company. Most of the world’s highest achievers read obsessively…

Billionaires Read Obsessively

Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s billionaire partner at Berkshire Hathaway, says,

“In my whole life, I have known no wise people who didn’t read all the time. None. Zero. You’d be amazed at how much Warren reads — and at how much I read.”

—Charlie Munger

Mark Cuban began his billionaire career this way:

“I read every book and magazine I could. I would tell myself one good idea would pay for the book and could make the difference between me making it or not.”

—Mark Cuban

The key is to actually do it. Says Mark Cuban,

“The same information was available to anyone who wanted it. Turns out most people didn’t want it. Most people won’t put in the time to get a knowledge advantage.”

—Mark Cuban

It’s Not Just Effort—Work Smarter, Not Harder

But effort is just part of the equation. You can’t just put in time mindlessly. You might spend hundreds of hours reading, but have nothing to show for it.

Tell me if this sounds familiar: you read a self-improvement book and get super pumped about all the awesome changes you’re going to try. You start off the next day really jazzed and change that one thing about your life.

But then each day passes, and your motivation disappears. Your memory starts fading. You forget what you read, and why you cared so much.

After a week, you can’t for the life of you remember what it was about, other than a vague 1-sentence summary.

Don’t worry—this is incredibly common. It’s the result of not learning as effectively as you can. What you spent all this time reading didn’t stick, so it has zero chance of improving your behavior. (It’s also sometimes the result of a bad, illogical, unconvincing author—we’ll get to that later.)

Now, some people try to learn more by doing the above 100 times. They spend all their time reading (ever seen someone brag about how many books they read?), but they keep forgetting what they read. What does 100 times zero equal? Zero. Spending time like this is like pouring water into a leaky funnel—none of it ends up where you want it to and your results are bad.

Instead, you need to learn how to learn. Learning the right way will accelerate your learning by 200% or more.

Think about it this way—for all the thousands of hours you’re going to spend learning in your lifetime, isn’t it worth taking a few hours to learn how to learn? You might get hundreds of hours back for a huge return on investment.

Hopefully this all makes sense to you. Here are the Top 6 Strategies for Reading and Learning that I’ve collected over 20 years of learning. They usually come from people far smarter and more accomplished than me.

Disclaimer: I founded this company, Shortform, as my own personal learning tool. Shortform is a learning app that summarizes the world’s best content, including non-fiction books and articles. You obviously don’t need Shortform if you want to learn effectively—but if you want to try learning faster, give Shortform a try. Thousands of business executives, CEOs, and lifelong learners use Shortform to learn more in less time.

Step 1: Learn How Your Brain Learns

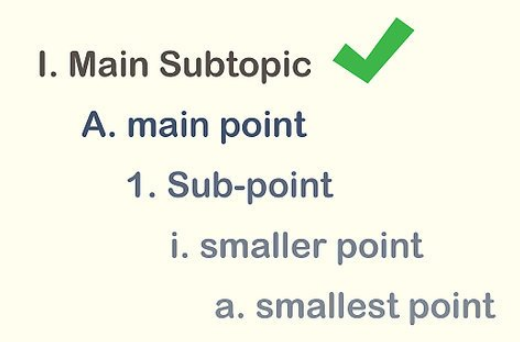

To learn effectively, you need to treat knowledge like a tree. Understand the big idea, and only then understand the details—do not learn the other way around.

This idea is most famously attributed to Elon Musk (who taught himself rocket science by reading):

“It is important to view knowledge as sort of a semantic tree — make sure you understand the fundamental principles, i.e. the trunk and big branches, before you get into the leaves/details or there is nothing for them to hang on to.”

—Elon Musk

Let’s clarify what this means, covering the trunk, branches, and leaves in order.

To learn something new, you need to find the basic BIG idea and make sure you understand it. Get rid of all the details, examples, and anecdotes. What is the BIG idea? This is the big, solid trunk of the tree.

Once you have the trunk firmly planted, then you can focus on adding to it. The basic big idea you started with is usually an oversimplification—there are nuances and secondary ideas that flesh out the big idea. These are branches that attach to the trunk. They build on the big idea; but without the trunk in place, the branches have nothing to add onto.

Finally, there are details that aren’t critical to the main concepts, but they add to your understanding and help you remember. Examples include supporting data, anecdotes, and other evidence. These are the leaves. They attach to the branches, which attach to the trunk. Without the trunk, the leaves have nothing to attach to.

Trunk, branches, leaves.

Even if you’ve never thought about learning this way before, it makes intuitive sense. This is why once you learn a fundamental skill, it’s easier to build on it with more complicated skills.

Say you’re learning how to cook—you need to first learn how to hold a knife and do a basic chop of a carrot. Then, and only then, can you learn how to do a julienne cut, chop garlic, and finely dice tomatoes. Trunk, branches, leaves.

Knowledge Tree in Reading

But the knowledge tree isn’t as obvious when you think about reading and learning abstract things. Let’s walk through a simple example from the well-known book Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance.

Trunk: Grit is the combination of passion and perseverance. Passion means sticking with a goal over the long-term. Perseverance means overcoming setbacks.

- Branch: Grit is more important than talent in achievement. Talent is overrated.

- Leaf: Grit matters more because it increases the amount of effort you expend. Talent is just untapped potential. In contrast, even with less talent, if you apply more effort, you’ll grow your skills more quickly and achieve more

- Leaf: Multiple studies show that grit is a good predictor of success: it predicts GPAs in college students; it predicts graduation rate among West Point students.

- Branch: Grit is changeable. It’s not just a genetic characteristic.

- Leaf: Genetic studies show that only a minor portion of grit is heritable—the bulk of each person’s grit is in the environment.

- Leaf: In a survey of US adults, grit rises steadily with age.

You can see how each part of the tree builds meaningfully on the last to form a clean, logical argument. You can also see how each of the leaves by themselves mean little if they’re not attached to the trunk or a branch.

Traditional Education Failed Us

The problem is, we were never really taught this way in school.

- When we’re taught physics, we’re shown endless complicated formulas to plug numbers into. But we don’t really learn the trunk of how forces behave, and how acceleration works. We don’t develop an intuition for the big ideas, which is why people feel so uncomfortable with science.

- When we’re taught history, we’re forced to memorize endless facts about people doing things. We don’t learn the patterns of why people behave the way they do. That’s why you promptly forget nearly everything you learned in history class after you cram for a test.

Even professional educators don’t understand this. Ever had a college professor go on and on, with you confused about what the point even was? They didn’t get the trunk-branch-leaf model.

And because you were never taught this way in school, you probably never thought to think this way in the rest of life.

To make the problem worse, most popular non-fiction books aren’t written in the trunk-branch-leaf trunk model either. Instead they’re “narrative first,” using a story to spark human interest, then weaving the big ideas around the narrative. Their chapters read something like this:

- Story 1 intro

- Principle A

- Story 1 continuation

- Principle A and B

- New story 2

- Principle C

- End stories 1 and 2

Does this sound familiar?

Personally, this drives me nuts when I’m reading a book to learn its big ideas. The author makes me work extra hard to extract the underlying truths. (Of course, certain genres like fiction or biographies are usually exempt from this, where the point is to enjoy the journey.)

Learn Principles-First

That’s why, when I read a book, I do what Elon Musk does—find the big idea, the supporting ideas, and then use the anecdotes and examples to illustrate the message.

At Shortform, where we create high-quality book summaries of non-fiction books, we call this structure “principles first.” We make the logical argument first, then use examples to support the logic. Our summaries look something like this:

- Principle A

- Short illustrative example

- Principle B

- Short illustrative example

- Principle C

- Full Story 1 connecting to all principles

This structure reorganizes the text to much better suit how the brain organizes information. We build the trunk of the tree, then hang the branches on the trunk. It lets us see the logical skeleton of the text and how all the pieces fit together – or, if the author is logically sloppy, how they don’t. It allows us to prune unimportant examples and concepts to make better use of our readers’ time.

Here are a few examples of how we do this:

- Grit and Outliers. The original books weave principles and stories together. We start with the principle first, then use key examples for illustration.

- For How to Win Friends and Influence People, we found a repeatable structure for each chapter: splitting into principles, tactics, and examples. Note that for unclear principles or tactics, we include short examples to illustrate the point right away.

The ideas are front and center (the trunk), the nuances and supporting ideas are next (the branches), then we add key examples and anecdotes to support and add color (the leaves).

You obviously don’t need to use Shortform to learn this way. But if this sounds like an appealing way to learn, sign up and check out our free sample summaries.

Step 2: Read Broadly

It’s great to read a lot, and deeply in one area. If you’re a computer programmer, you should read a lot about how to be a better programmer (keeping in mind the trunk, branches, and leaves model). If you’re a salesperson, you should read a lot of books on sales tactics. And so on.

But this isn’t the way to maximize your potential. The best ideas don’t just come from reading narrowly in a single field. They come from reading broadly, in areas that aren’t directly outside your immediate focus.

If you’re a programmer, you should read about marketing and product design. If you’re a salesperson, you should read about psychology and conflict resolution. And everyone benefits from reading about human relationships, economics, and science.

Let’s turn once again to someone far smarter and more successful than me. Charlie Munger is Warren Buffett’s long-time partner at Berkshire Hathaway. Together with Buffett, they’re literally the best investors in all of modern human history. Berkshire Hathaway is worth over $500 billion.

What’s the secret to their success? Not just reading—but reading broadly:

“I’ve long believed that a certain system— which almost any intelligent person can learn— works way better than the systems that most people use. What you need is a latticework of mental models in your head. And, with that system, things gradually get to fit together in a way that enhances cognition.

The models have to come from multiple disciplines—because all the wisdom of the world is not to be found in one little academic department. That’s why poetry professors, by and large, are so unwise in a worldly sense.”

—Charlie Munger

As he describes in his book Poor Charlie’s Almanack, mental models come from fields as diverse as:

- Math, such as compound interest, normal distributions, and decision trees

- Psychology, such as consistency bias, social proof, and reciprocity

- Physics, such as critical mass, autocatalysis, and equilibrium

- Economics, such as advantages of scale, opportunity cost, and tragedy of the commons

Charlie Munger and Warren Buffett use these diverse ideas to better understand the world, such as how people behave in economic booms and recessions. They then trade on this information, earning superior returns.

Dilbert creator Scott Adams has similar career advice:

“If you want something extraordinary, you have two paths:

1. Becomes the best at one specific thing.

2. Become very good (top 25%) at two or more things.The first strategy is difficult to the point of near impossibility. Few people will ever play in the NBA or make a platinum album. I don’t recommend anyone even try.

The second strategy is fairly easy. Everyone has at least a few areas in which they could be in the top 25% with some effort. In my case, I can draw better than most people, but I’m hardly an artist. And I’m not any funnier than the average standup comedian who never makes it big, but I’m funnier than most people. The magic is that few people can draw well and write jokes. It’s the combination of the two that makes what I do so rare.”—Scott Adams

So read broadly. Read in areas you think you have zero interest in. You’ll be surprised by how useful it is.

I challenge myself to read about subjects that I might otherwise think have zero relevance to me, such as self-help books for women and biographies about people from centuries ago. I’ve picked up some of the best lessons in work and life from doing this. By reading broadly, I start seeing connections between ideas, like:

- How biological feedback loops are like business flywheels

- How evolutionary theory explains why we feel depression and why it’s so easy to get fat in modern times

- How universal psychological biases explain how we’re so easily manipulated by advertising and politicians

Likewise, you can learn valuable lessons from reading books that you might think don’t apply to you:

- Even if you’re never going to start your own business, read Lean Startup to figure out how to start any project the right way, from a home renovation to applying to new jobs

- Even if you’ve never experienced serious emotional trauma yourself, read The Body Keeps the Score to understand your friends and family who have.

- Even if you’re not a professional negotiator, read Never Split the Difference to learn how to negotiate everything from job offers to splitting up chores at home.

That’s why at Shortform, our book summaries cover every non-fiction genre, including business, history, self-improvement, health, psychology, and much more. We make it easier for you to dip your toe into new areas and access ideas that you otherwise wouldn’t sit down and read a full book for.

Find the books that will change the way you see the world.

Want to learn from all those books you don’t have time to read? Check out Shortform.

Shortform has the world’s best summaries of nonfiction books and articles. Even better, it helps you remember what you read, so you can make your life better. What’s special about Shortform:

- The world’s highest quality book summaries—comprehensive, concise, and everything you need to know

- Broad library: 1000+ books and articles across 21 genres

- Interactive exercises that teach you to apply what you’ve learned

- Audio narrations so you can learn on the go

Sound like what you’ve been looking for? Sign up for a 5-day free trial here.

Step 3: Turn Ideas Into Action

If you’re like me, you don’t read purely for fun. When you read, your ultimate goal is to improve your life. You want to learn a new idea to try out. You want to change your behavior to bring you one step closer to your goals.

That’s why just reading and learning isn’t enough.

Says entrepreneur and writer Derek Sivers,

“If more information was the answer, then we’d all be billionaires with perfect abs.”

The important thing is not just to memorize a bunch of facts. You need to get out the door and do something with it.

Famous speaker Tony Robbins says something similar:

“What you know doesn’t mean shit. What do you do, consistently?”

—Tony Robbins

Know anyone who’s book smart, but never seems to have their life together? They can rattle off all the things you “should” be doing—but they never seem capable of actually doing what they suggest.

This is because they learn a lot, but they don’t focus on the actionables.

When you read, actively think about applying the concepts to your life. Think about these 3 questions:

- What key question should I be asking about my life?

- What are the top 3 takeaways from this book that I’ll apply for the rest of my life?

- How am I going to behave differently now that I’ve read this book?

Actionables are critical to getting more value out of what you read. Think of it as a return on investment – reading the book is just the first part and might take, say 5 hours. Reflecting on the lessons and focusing on actionables might take one hour, but double or triple your return on investment from the book.

In Shortform, every one of our summaries has interactive exercises building off the book that push you to apply the lessons to your own life. You’ll be challenged to reflect on past experiences and ask what you could have done better, or to prepare for future events. Take this example from How to Win Friends and Influence People:

Exercise: Reapproach Your Argument

1) Think about a recent argument where you felt you were both talking over each other. What was it about? How did it begin? How did it escalate?

2) Try to approach the argument in a new way. (Remember: have a friendly approach; respect the other’s opinions; if you’re wrong, admit it; see things from the other point of view; sympathize with the other person.) What would you say?

3) Now that the other person feels heard, you can speak. (Remember: start with where you agree; appeal to their interests; lead them to your idea; appeal to their best self and give them a good reputation to live up to; make your idea vivid.) What would you say?

Or this one from 12 Rules for Life:

Exercise: Judge Yourself in a New Way

Instead of judging yourself by other people’s standards, redefine your goals to find a new way to measure yourself.

1) What is the “one” most important thing that you typically obsess over and want to achieve? The thing that makes you miserable because you don’t have it. Describe your desire.

2) Besides that, your existence is multidimensional. What are all the other things important to you that you should measure yourself by?

3) Picture someone you envy who has that “one” thing you really want from the first question. Does that person also succeed on all the other dimensions you listed in the second question? If not, what does this mean about how you should perceive that person?

Isn’t thinking through these types of questions is fantastic? How much more useful are books when they’re actually applied to your life? How much better will you remember the principles and apply them the next time you need it most?

If this looks useful to you, sign up for Shortform and check out our exercises for your favorite books. They might push you to learn from the book in ways you didn’t think through the first time.

Step 4: Make Learning a Habit

Warren Buffett is famous for reading relentlessly. In fact, he spends most of his day reading. In a commencement speech, he shared his secret to success:

“Read 500 pages…every day. That’s how knowledge works. It builds up, like compound interest.”

—Warren Buffett

Knowing that most people would be skeptical it was really this simple, Buffett added,

“All of you can do it, but I guarantee not many of you will do it.”

—Warren Buffett

You need to make learning a habit. Every single day, you should think about how you’re improving yourself. I’ll let Buffett’s partner Charlie Munger talk about this:

“I constantly see people rise in life who are not the smartest, sometimes not even the most diligent, but they are learning machines. They go to bed every night a little wiser than they were when they got up and boy does that help, particularly when you have a long run ahead of you.”

—Charlie Munger

Let’s return to what Buffett said about how knowledge works, like compound interest. Learning compounds because learning new things makes you learn the next thing faster and better.

Learning is like a savings account that you keep investing in. The more time you spend learning, the more deposits of knowledge you make, the faster the account grows.

Here’s how this works, concretely:

- If you learn introductory material to a new subject, you can dive deeper and learn expert knowledge that’s more valuable. (Remember that Elon Musk started multi-billion dollar company SpaceX by reading about rocket science.)

- If you learn how to become superhumanly productive, you can save yourself hours each day—which you can then reinvest back into learning.

- If you learn how to create stronger relationships (either romantically, with friends, or colleagues), you end up happier and spend less time worrying about your social life—more time you can reinvest into learning.

- If you learn how to make more money, you can buy yourself the lifestyle you always wanted. This gives you more free time—which you can reinvest into learning.

Get the idea? The more you learn, the better your life gets and the smarter you get, which lets you learn even more. And so on and on you go.

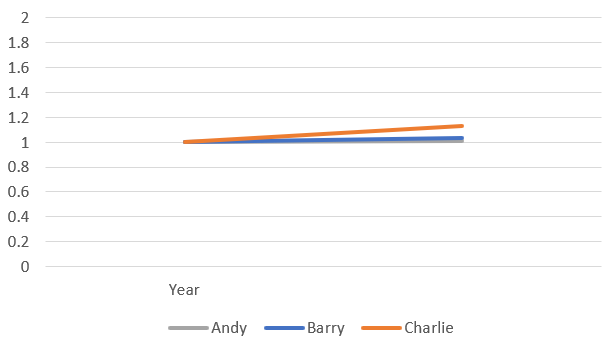

Let’s say every book you read added 1% to your total knowledge base. Does this sound reasonable?

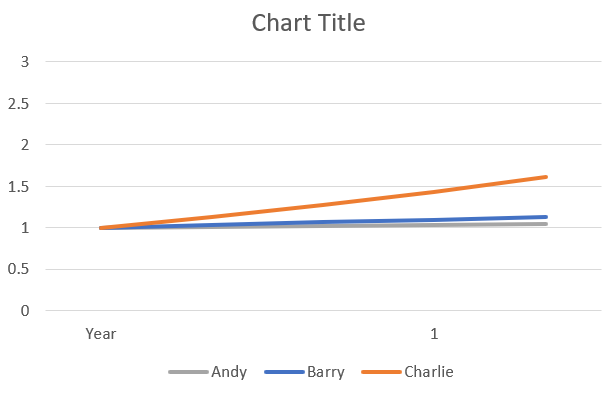

It doesn’t sound like much, but it makes a huge difference over time, the more you learn. Let’s compare 3 people who all start off with the same amount of knowledge, but who read different amounts:

- Average Andy: reads 2 books a year, or 1 book every 6 months.

- Bored Barry: reads 6 books a year, or 1 book every 2 months.

- Constantly-reading Charlie: You read 24 books a year, or 1 book every 2 weeks.

They all start off with the same amount of knowledge. After 6 months, not a ton changes. Andy, having read one book, is smarter by just 1%. Constantly-reading Charlie is up by 12%.

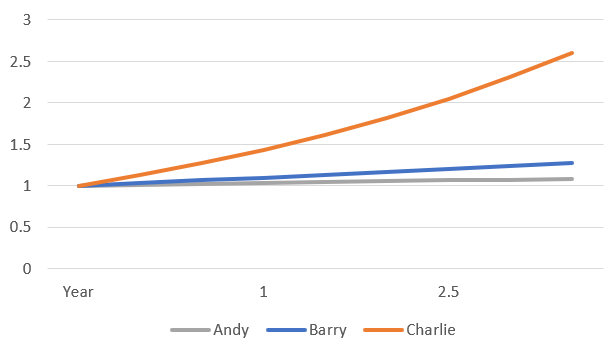

After 2 years, the differences are bigger. Andy has just read 4 books and is smarter by 4%. Barry is a bit further along, at 12%. But Charlie is leaps ahead – he’s now 60% smarter; he gained 15 times the knowledge that Andy did in the same time.

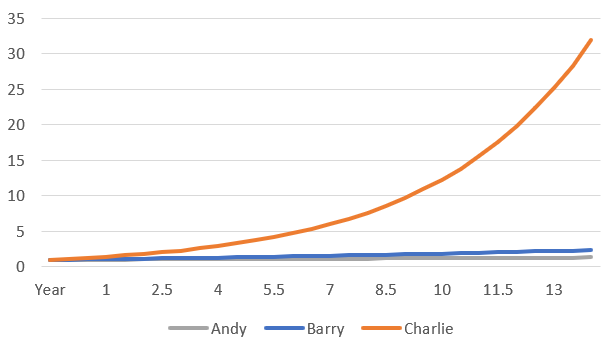

After 4 years, they separate even further:

Finally, after 10 years, the differences are huge.

- Andy is 22% smarter than when he started. It’s better than nothing, but it’s not much over 10 years.

- Barry’s a bit further along, at 82% smarter. He gained nearly 4 times the knowledge that Andy did.

- Charlie is in an entirely different league. He’s increased his knowledge by 989%. He’s now 6 times smarter than Barry, and 9 times smarter than Andy.

What difference do you think this knowledge makes in Charlie’s life? He’s probably way further along in reaching his goals; he makes better decisions; he has more access to resources; he’s happier and has stronger relationships.

Meanwhile, Andy’s wondering why his life is barely any different than where he was years ago.

Knowledge compounds. The more you learn today, the faster you learn tomorrow. Like a rolling snowball, this keeps gathering more and more momentum.

If you don’t look back at yourself 2 years ago and think, “wow that person was an absolute idiot,” you’re not learning enough.

Shortform makes it easier for you to learn. We put the world’s best ideas into a summarized form, so you get key insights with less time.

Want to learn from all those books you don’t have time to read? Check out Shortform.

Shortform has the world’s best summaries of nonfiction books and articles. Even better, it helps you remember what you read, so you can make your life better. What’s special about Shortform:

- The world’s highest quality book summaries—comprehensive, concise, and everything you need to know

- Broad library: 1000+ books and articles across 21 genres

- Interactive exercises that teach you to apply what you’ve learned

- Audio narrations so you can learn on the go

Sound like what you’ve been looking for? Sign up for a 5-day free trial here.

Step 5: Review What You Learned

Tell me if this sounds familiar. You read a book, then forget what you read just a few days later. Even worse, when you reach the end of a book, sometimes you might not even remember the beginning of the book!

You can’t apply knowledge that you’ve lost. Knowledge doesn’t compound if you don’t have it. Analogy: in personal finance, your investment account doesn’t compound if you keep making withdrawals.

This is a key insight from research into how the best learners learn. You need to retain knowledge to do anything with it.

So how do you do this? Really, it’s just two easy steps:

Step 1: As you read, take notes.

Most readers just highlight without taking notes. Highlighting is better than nothing, but it’s more passive than active. Ideally, you should take active notes. Says Bill Gates:

“For me, taking notes helps make sure I’m really thinking hard about what’s in the book.”

When I take notes, I usually try to answer these questions:

- If the section is convoluted, what is the author really trying to say, in dumb simple terms?

- What does this idea remind me of? Connect one book to other books to build a web of knowledge.

- Do I disagree with what the author’s saying?

In this way, you build your own knowledge tree.

This is how Shortform started – as a hobby. I wrote my own detailed, comprehensive summaries of my favorite books, like Lean Startup and Thinking Fast and Slow. It took a lot more time than just highlighting, but I remember these books even 5 years after reading them. I distilled the book into its key information so I could remember what I read years later. Luckily, at Shortform we publish all these summaries so you don’t have to write your own—it’s not as good as writing your own notes, but it’s still very effective.

Step 2: Review your notes regularly, using spaced repetition.

Keep a list of your favorite books, those with lessons that you really want to remember for a lifetime.

Then pre-schedule the next time you want to review your notes. Instead of taking the time to read a new book, review your notes for the old book.

Another learning trick here is to use spaced repetition. When you first learn something, you forget it pretty quickly. Therefore, you need to review it soon after to lock it into place.

Once you review it once, the information decays more slowly. You can wait a bit longer to review it again. Once you do review it a second time, the information decays even more slowly, so you can wait longer until you review it next.

Here’s what that looks like:

My personal schedule of review looks something like:

- 2 weeks

- 4 weeks

- 8 weeks

- 20 weeks

- Once or twice a year, as needed

I literally slot this into my calendar like an appointment, so I don’t forget.

The good news is, Shortform makes it easier for you to remember what you read. Our comprehensive summaries don’t miss important details, so you regain that feeling of having just read the book.

You can highlight and take notes on Shortform too. Then we show you your key highlights to refresh your memory.

How Many Books to Review?

Now, if you read a lot of books, this might sound like it’ll quickly accumulate a lot of review tasks, and you might not have any time to read new books!

Rest assured, you should only be doing this for books you think are paradigm-changing for how you understand the world. Reviewing these books You might only have 5-10 of these. My personal list includes:

- Thinking, Fast and Slow: how cognitive biases cause you to make terrible decisions

- The Lean Startup: the best business book I’ve ever read—move fast and test cheaply. Worth reviewing whenever starting a new project of any kind

- Basic Economics: fundamental ideas around how our economy works

- Atomic Habits: how to develop good habits (useful to review whenever you want to start a new habit)

- Crucial Conversations: the best guide to defusing heated arguments I’ve ever read.

These books all totally changed how I view the world and make decisions, and they’re well worth the time to nearly memorize.

You might have your own list of favorite books. Make sure you review them regularly.

Step 6: Make the Best Use of Your Time

We’ve talked a lot so far about billionaires who read a lot—Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, Mark Cuban, and so on.

Well, billionaires have plenty of time to read. But what about the rest of us?

Between work, family, social life, and health, it doesn’t seem like we have enough time to learn everything we want, let along do everything we want.

So how can you get the knowledge of one book per week, if you don’t have the time to read it all?

Try reading high-quality book summaries. When you want the key ideas in the book, organized logically and without any fluff, read Shortform summaries. We’ve written the world’s best summaries:

- They’re comprehensive. We include all the useful points from the book worth knowing.

- They include key examples and anecdotes to support the ideas.

- They cut out all the fluff. If you’ve ever been frustrated by a rambling author, our summaries cut straight to the point.

- They feature original exercises and actionables, designed to get you to apply the book’s ideas to your everyday life.

These aren’t your typical book summaries, which read more like someone slapped together a few interesting points from the book.

A book summary will never be a replacement for the original book. But it can be a great way to learn a book’s ideas, the same way a great college lecture teaches as well as a textbook (and maybe even better).

There you go: the 6 learning strategies that get me through life and learning more than ever:

- Build a knowledge tree.

- Read broadly. Build a network of diverse mental models.

- Turn ideas into action. Focus on applying what you learned.

- Make learning a habit. Learn every single day to compound knowledge.

- Take notes. Review what you learned.

- Learn more in less time.

Want to learn from all those books you don’t have time to read? Check out Shortform.

Shortform has the world’s best summaries of nonfiction books and articles. Even better, it helps you remember what you read, so you can make your life better. What’s special about Shortform:

- The world’s highest quality book summaries—comprehensive, concise, and everything you need to know

- Broad library: 1000+ books and articles across 21 genres

- Interactive exercises that teach you to apply what you’ve learned

- Audio narrations so you can learn on the go

Sound like what you’ve been looking for? Sign up for a 5-day free trial here.

Decent article writing wise but I disagree with the premise. I dont think reading is an end all be all thing in terms of intellect, in fact I feel most of my intellect has been because of my thinking. I honestly kind of feel the very idea is a lie. Not that it doesnt work, but that it is looked at as an inherently better option, I think is false. I dont see what it would do different over experiencing, seeing and feeling. They all have their benefits. There is value in absorbing information I think would be a better premise for the article, but I understanf thats a much less interesting premise. Also, the whole billionaire thing was kind of silly. Dont attribute self worth to money. You mean something because everyone does, and pretending a billionaire status makes you inherently more intelligent in more than a very specific sense, usually logically and instinctively, and that its an overall good thing just doesnt make sense to me. A billion is a LOT, and if were being frank those people did not make their money in a pure way. They are not good people, and saying they are better than you because they have a bigger bank account seems like an insecure idea. In the article you use the premise of a billionaire as a foundation for their idea being accurate which I think is demonstrably false also.