This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Road Less Stupid" by Keith Cunningham. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Are you a leader that people depend on? How can you avoid mistakes at work?

Mistakes are bound to happen in the workplace, but the great thing is that you can learn from them. Keith Cunningham’s book The Road Less Stupid says that you’ll be able to avoid making the same mistakes twice if you take the time to think about your decisions before making them.

Continue reading to learn how to avoid mistakes at work.

Avoid Mistakes by Taking Time to Think

Cunningham’s solution to learning how to avoid mistakes at work is to set aside blocks of time for deep thinking that force you to confront issues and answer questions you might otherwise have failed to consider. Schedule thinking sessions at least twice a week and ideally every day.

Each thinking session is one hour long: You spend the first 45 minutes pondering questions or problems and jotting down possible answers or solutions. Then you spend the final 15 minutes evaluating the ideas you came up with and documenting any that are good enough or important enough to warrant following up on—whether in a future thinking session or as actionable business directives.

(Shortform note: In Six Thinking Hats, psychologist Edward de Bono elaborates on the process of thinking, explaining that there are six fundamental types of thinking. De Bono observes that our thinking is often a jumble of all six types and argues that you can think more coherently and productively by consciously separating them. Cunningham appears to be doing just that with his thinking sessions by dedicating the first 45 minutes to generating ideas (what de Bono labels “green hat thinking”) and then 15 minutes to evaluating them (“black hat thinking”).)

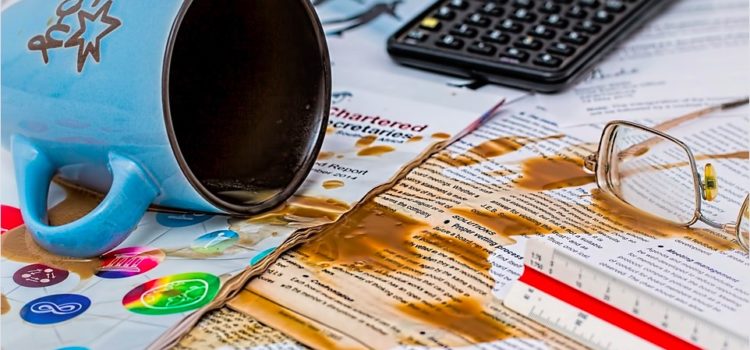

Cunningham stresses the importance of minimizing distractions during your thinking sessions so you can focus deeply on questions and issues. In addition to blocking off the time in your schedule so that you won’t be interrupted, he recommends setting aside a specific place for thinking, such as a separate desk or a chair in a corner of your office where your computer screen and other reminders of pending tasks will be out of sight. He even has a separate pen and notebook that he uses only for documenting questions and ideas during thinking sessions.

(Shortform note: We’ve compiled additional methods, tips, and resources for avoiding distractions and focusing deeply in a Master Guide to Focus. For example, some authors observe that you’re naturally better able to focus deeply at a certain time of the day, which can vary depending on your chronotype (your body’s particular circadian rhythm). Others observe that consistently engaging in a rewarding activity, such as a relaxing walk outdoors, right after your sessions of intense thinking can train your brain to associate your thinking with the pleasurable break that follows, reducing stress and making it easier to maintain your focus.)

What to Think About

Cunningham advises you to start each thinking session with at least one question that you want to ponder but no more than three so you can focus deeply on them and get past the obvious, superficial answers to more original, insightful answers. He observes, though, that once you start thinking about a question, it often spawns other questions. Also, most important questions take more than one session to really think through, so don’t worry if you don’t answer all your questions in a given session.

What specific issues should you ponder in your thinking sessions? Aside from contemplating whether you’re making any of the mistakes that he calls out specifically, Cunningham discusses a number of general questions you’ll probably need to ask from time to time, so consider starting your thinking session with one or more of the following:

1) What questions or issues are most important for you to consider right now? Cunningham urges you to periodically ask yourself whether you’re asking the right questions. He notes that when you can’t seem to come up with a good answer to a question or problem, it’s often because you’re asking the wrong question.

2) What are the real problems you need to solve? Are the problems you’re currently trying to solve the actual root problems or just symptoms of an underlying problem? You might spend a thinking session listing possible causes for a given problem, or listing actions and events and asking yourself whether the problem would go away if a given event happened or stopped happening.

3) What can you do to solve a certain problem? Once you figure out what the real problem is, ask yourself what you (and your organization) can do to overcome it. We’ve discussed the difference between goals and plans. Solving the problem is your goal, now you need to plan your solution. As you make your plan, ask yourself what you need to change about your corporate focus or strategy, as well as how you’ll need to reallocate resources and rethink your metrics to support the change of focus.

4) What are your assumptions? As you consider any change or new venture, Cunningham advises you to think about the assumptions you’re making in assessing its potential. Consider whether the assumptions are reasonable and how you could validate them. Unfounded assumptions can lead to stupid mistakes, especially if you don’t realize you’re making the assumption until it proves to be false. You’ll want to consider the risk of each assumption turning out to be wrong.

5) What are the unintended consequences? Cunningham observes that even if none of the risks that could hinder the success of your project are realized, the project itself could have unintended consequences that pose another kind of risk. For example, maybe you roll out a new product with special safety features, and people trust the new features so much that they take bigger risks when using it, such that the new safety features actually result in an increase in injuries.

Rethinking Human Errors

In The Design of Everyday Things, engineer and cognitive psychologist Don Norman explains how misconceptions about human error can prevent us from correctly identifying root causes, perpetuate poor assumptions, and precipitate unintended consequences. Thus, you may be able to make your thinking sessions more effective by rethinking how you think about human error in light of Norman’s discussion.

Norman observes that when people are looking for the root cause of a problem, especially a problem that caused an accident, they tend to conclude the search as soon as they find a person to blame. If someone did something wrong and that caused or substantially contributed to the problem, then the root cause gets labeled as “human error,” and the investigators rarely stop to ask why the person made the mistake. Often, Norman argues, human errors are actually a predictable result of poorly designed systems.

As he goes on to explain, frequently the problem is that people who design machines or other systems unconsciously assume that their users don’t make mistakes. But all humans have physical and mental limitations. For example, you can only focus deeply on a given task for a certain amount of time, and even then, interruptions can disrupt your focus. And a person may not remember to do everything she’s supposed to do if her focus lapses or is disrupted.

Norman warns that when real, fallible people operate systems that were designed for hypothetical infallible people, the unintended consequences can be severe. For example, the SL-1 nuclear reactor was designed such that the control rod (which slides in and out of the core to adjust the power output of the core) had to be lifted slightly by hand to attach it to the mechanism that would raise and lower it in normal operation. The operating procedure for the reactor specified that it should never be lifted more than four inches by hand.

One day, when workers were re-starting the reactor after it had been shut down for a while, the control rod got stuck. When a worker pulled on it hard enough to get it moving, he accidentally lifted it too far. This triggered a power surge in the core, causing the reactor to explode and killing the workers.

Thus, as you contemplate whether you’re solving the right problems, remember to look beyond human error to see if a system, device, or process needs to be redesigned. As you try to identify your assumptions, consider how you expect customers, employees, and other people to behave, and ask yourself whether your expectations are consistent with normal human limitations. And as you contemplate unintended consequences, don’t forget the possibility of people misusing your product or system.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Keith Cunningham's "The Road Less Stupid" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Road Less Stupid summary:

- That the secret to financial success is to avoid making stupid mistakes

- The most common stupid mistakes executives make and how to avoid them

- Why doing what you love does not always translate to making money